Abstract

The Entente cordiale was a series of formal political agreements signed in 1904 that negotiated the peace between England and France. French for “warm understanding,” the Entente cordiale of 1904 settled more immediate disputes between England and France in Egypt, Morocco, and elsewhere in Africa. Perhaps more famously, the series of agreements signed in 1904 contributed to the harmonization of relations between the two countries in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But, as I show here, the Entente cordiale of 1904 also served as the culmination of a more informal—and precarious—entente that had slowly developed between the former enemies beginning in the 1830s and 1840s.

*On 8 April 1904, a series of agreements between England and ![]() France known as the Entente cordiale were signed. The product of long-running discussions between the two former rivals, the agreements officially marked the end of hostilities that intermittently flared across

France known as the Entente cordiale were signed. The product of long-running discussions between the two former rivals, the agreements officially marked the end of hostilities that intermittently flared across ![]() the Channel, settled more immediate questions of imperial expansion, and (re)distributed power in contested sites, including

the Channel, settled more immediate questions of imperial expansion, and (re)distributed power in contested sites, including ![]() Egypt,

Egypt, ![]() Morocco,

Morocco, ![]() Senegal, and

Senegal, and ![]() Nigeria. Historians have tended to focus on the imperial conflicts that led to the signing of the agreements, including those in Egypt and in Africa, as well as the legacy of the Entente in the twentieth century. What has attracted less attention are the ways in which the 1904 agreements served to formalize the more informal entente cordiale (French for “warm understanding”) that existed between England and France during the nineteenth century and paved the way for the British and French to join forces against German aggression during World War I.

Nigeria. Historians have tended to focus on the imperial conflicts that led to the signing of the agreements, including those in Egypt and in Africa, as well as the legacy of the Entente in the twentieth century. What has attracted less attention are the ways in which the 1904 agreements served to formalize the more informal entente cordiale (French for “warm understanding”) that existed between England and France during the nineteenth century and paved the way for the British and French to join forces against German aggression during World War I.

The entente cordiale first began developing between England and France ![]() with the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo in 1815. The Congress of Vienna secured a tenuous peace on the Continent and ushered in a new era of Anglo-French relations that were defined, at least in part, by a gradual warming. Edward Bulwer-Lytton acknowledged this warming trend as early as 1833 in his England and the English when he described a sea-change in English views of the French to the French diplomat Talleyrand: “We no longer hate the French” (42; italics in original). While it may be tempting to read Bulwer-Lytton’s claim as a reflection of an actual wholesale change in English attitudes toward the French, it would be better to see it as an attempt to create a new zeitgeist that conformed more closely to the spirit of the entente. By the 1840s, the warming trend had blossomed, and the term entente cordiale first entered into the British political lexicon.

with the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo in 1815. The Congress of Vienna secured a tenuous peace on the Continent and ushered in a new era of Anglo-French relations that were defined, at least in part, by a gradual warming. Edward Bulwer-Lytton acknowledged this warming trend as early as 1833 in his England and the English when he described a sea-change in English views of the French to the French diplomat Talleyrand: “We no longer hate the French” (42; italics in original). While it may be tempting to read Bulwer-Lytton’s claim as a reflection of an actual wholesale change in English attitudes toward the French, it would be better to see it as an attempt to create a new zeitgeist that conformed more closely to the spirit of the entente. By the 1840s, the warming trend had blossomed, and the term entente cordiale first entered into the British political lexicon.

From its entrance into the political lexicon, this “warm understanding” proved to be precarious, tangled in the complex web of each nation’s imperial and trade relations. As historian R.J. Bullen points out in his analysis of the entente cordiale, the new “warm understanding” shaped two very different types of foreign policy in England. According to Bullen, Lord Aberdeen, who acted as Foreign Secretary between 1841 and 1846, pursued a conservative foreign policy that tended to emphasize mutual trust and understanding and underscored Britain’s obligations in Europe. But, as Bullen also suggests, Lord Palmerston, who acted as Foreign Secretary between 1835-141 and 1846-1851, distrusted Aberdeen’s emphasis on mutual trust and understanding. Such trust, Palmerston feared, would undermine England as an imperial power by “[dragging] down England to the position of. . . acting in subserviency to the views of France” and forcing the English to act as the “mere foot boys of France” (qtd. in Bullen 30-1). As a result of his fears that England would become France’s puppet, Palmerston adopted a more aggressive, interventionist view of France as an enemy to be contained so that England could pursue her own goals on the Continent. As Bullen demonstrates, Palmerston’s view of the entente largely prevailed over Aberdeen’s. The aggressiveness of Palmerston’s foreign policy would have a lasting effect on the Anglo-French relationship, feeding both the anxieties that lingered in England as well as the hostilities between the two nations that intermittently flared throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century.

At the same time that the political relationship between the two nations developed and struggled, the commercial relationship between the two former enemies strengthened. Although he favored an aggressive approach to France, Palmerston also understood the interdependence of economic trade and mutual regard and kind feelings; in an 1842 speech on the Corn Laws, he defined commerce as “the interchange of mutual benefits engendering mutual kind feelings—multiplying and confirming friendly relations. It is, that commerce may freely go forth, leading civilisation with one hand, and peace with the other, to render mankind happier, wiser, better” (qtd. in Bourne 255). Commerce and trade, then, were fully compatible in this view with the spirit of the entente. As Ellen Moers demonstrates in her study of the development of the dandy, commerce with England took root in the fertile soil of Louis Philippe’s July Monarchy as émigrés seeking to support themselves by catering to English tourists returned home. French anglomanes eagerly (and, in the minds of French critics, crudely) indulged their tastes for all things Anglais: roast beef and potatoes, fashions (characterized by garish English colors), sports (including horse-racing and steeple-chasing), and transportation (Moers 114). In England, a similar Francophilia could be seen as the English indulged their hankering for all things French, including French novels and French luxury goods, such as wines, silks, flowers, textiles, and objets d’art. By the 1850s and 1860s, an exhibit and department store culture thrived on both sides of the Channel that made luxury increasingly available to bourgeois consumers in venues such as the Great Exhibit of 1851 and in department stores such as Le Bon Marché, which opened first in ![]()

Paris in 1852.

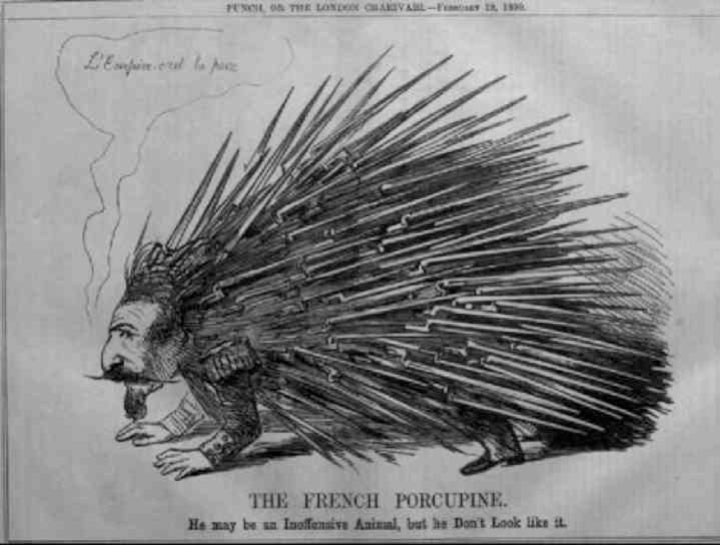

Despite a thriving commercial relationship that flourished between the 1840s and the 1860s, anxieties and Gallophobia continued to simmer in England, fueled both by fears of revolution and France’s imperial aggressiveness. The Revolution of 1848 swept through Europe (originating in France) that same year, provoking fears in Britain that the fires of revolution would leap across the Channel, and prompting a backlash against the French that eroded the stability of the entente. Further exacerbating this was the leader of the Second French Empire, Napoleon III, whose aggressive imperial actions on the Continent proved no less inflammatory to the English public than the thought of a revolution. Between 1848 and 1860, his actions occasioned three intense invasion panics in Britain. At the height of the third invasion panic in 1859, Punch ran an illustration titled “The French Porcupine” that captured the intensity of Victorian fears. (See Fig. 1.)

In the image, the figure of Napoleon III appears as the titular porcupine, proclaiming the peaceful intentions of the Second French Empire (“L’Empire, c’est la paix”—The Empire means peace), but completely undermining the Porcupine’s declaration of peace are his spines, which are made of bristling–and menacing–bayonets. England’s entrance into the ![]() Crimean War (1853-6) further aggravated tensions. (See Stefanie Markovits, “On the Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade.”) Although the joint alliance of the English and French during the war seemed to partake of the spirit of the entente, English sympathies with the French weakened when the war went badly. Irish politician John Croker’s 1854 letter to John Murray summed up the general public mood toward the French. Croker fearfully tells Murray that the entente has left him feeling “out of date—or at least out of season—for, I confess, I have a strong conviction that the present folly, as I think it, is likely to be short-lived, and to end in a terrible crisis” (253).

Crimean War (1853-6) further aggravated tensions. (See Stefanie Markovits, “On the Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade.”) Although the joint alliance of the English and French during the war seemed to partake of the spirit of the entente, English sympathies with the French weakened when the war went badly. Irish politician John Croker’s 1854 letter to John Murray summed up the general public mood toward the French. Croker fearfully tells Murray that the entente has left him feeling “out of date—or at least out of season—for, I confess, I have a strong conviction that the present folly, as I think it, is likely to be short-lived, and to end in a terrible crisis” (253).

In an effort to prevent the “terrible crisis” that Croker anticipated and feared–a war with France–the English and the French once again attempted to resuscitate the entente through commerce, this time through a formal free trade agreement. Richard Cobden and Michel Chevalier, the two great English and French free traders, brought their free trade agreement before the English and French publics in 1860.[1] Their proposal attempted to resuscitate the entente by establishing Britain and France as trading partners, conferring on each other most favored nation status, and lowering commercial trade tariffs on goods produced in both countries. The agreement allowed the English easier access to the famous luxury goods (including wines, silks, artificial flowers, cabinetry, and articles de Paris) produced in France that were in such high demand by bourgeois English consumers. The deal also allowed the French to access the raw materials they needed for industrialization, which they put to good use improving their navy and railroad system.

Fierce opposition to Cobden and Chevalier’s free trade agreement mounted in both England and France, but as William Gladstone, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, wrote in an undated memorandum, “It was and is my opinion, that the choice lay between the Cobden Treaty and not the certainty, but the high probability, of a war with France” (qtd. in Dunham 102). The sentiment was shared—at least in certain quarters—on the other side of the Channel. When the agreement was brought to the floor in early 1860, it was opposed both by English invasionists and French protectionists, but both English and French governments swiftly ratified the agreement. The opposition to the plan quickly died down, and the war between England and France that Gladstone and others had feared never broke out. The Anglo-French Agreement did guarantee the flow of materials and goods across the Channel and successfully stirred up commerce between the two nations. And, as The Times finally concluded in an editorial published on 25 February 1860, “there is not one of the Conservative body who has not dreamt long ago of a Commercial Treaty with France as the best thing that could happen to either of these countries” (11). Yet, as the same editorial also acknowledged, while the Anglo-French Agreement might have succeeded in preventing the outbreak of military hostilities, it had dampened Gallophobic sentiments in Britain only a little: “As a matter of sentiment, for example, we may all deplore that a treaty has been signed, and that the two Governments do not spontaneously vie with one another in doing what is even more beneficial to their own people than to their neighbors” (11).

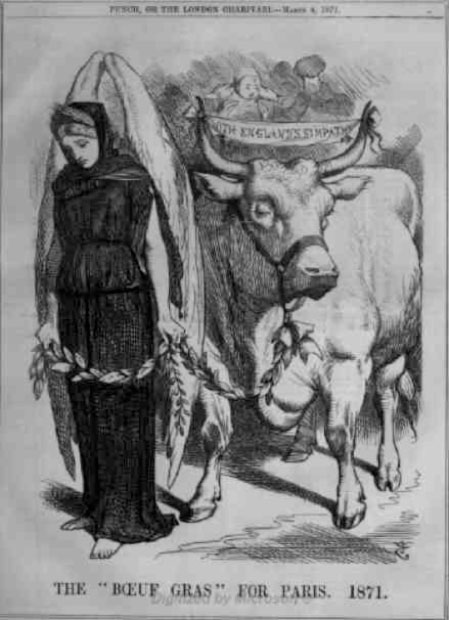

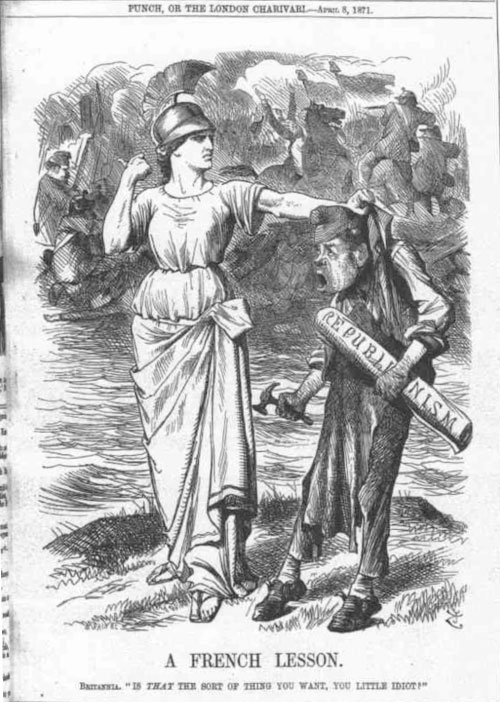

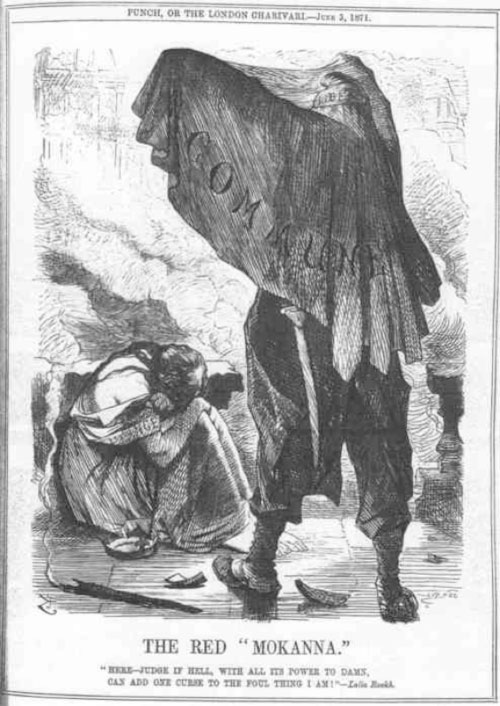

The Anglo-French Agreement helped assuage political tensions and posturing between Britain and France. The spirit of the entente continued to waver, but it nevertheless persisted through the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). Otto von Bismarck’s invasion of France prompted a variety of responses from the British just across the Channel. While some Victorians cheered the Germans,[2] many other Victorians responded to the spectacle of French suffering more in the spirit of the entente with massive outpourings of sympathy. British journalists reported back to their Victorian audiences from the front lines, often stirring up sympathy for the victims of the war (soldiers and civilians alike) by reporting on the cruel and inhumane practices of modern warfare, and French sympathizers in London organized and gathered together, creating philanthropic organizations that raised funds and secured resources to aid the French peasantry. Even Punch, which rarely passed up the chance to satirize the French, got into the act, publishing an illustration titled, “The ‘Bœf Gras’ for Paris. 1871.” at the end of the war. (See Fig. 2.) Lacking in Punch’s customary asperity and satire, the illustration features the mournful figure of Peace, leading the titular “Bœf Gras” (“fattened calf”). The sentiment emblazoned on the banner stretched between the calf’s horns–“With England’s Sympathies”–stands in stark contrast to the earlier Gallophobic sentiments of Punch’s “The French Porcupine.” The surprisingly generous show of sympathies for the French faded, however, during the brief rule of the Paris Commune between March and May 1871. The Commune rose to power when the provisional head of the French government, Adolphe Thiers, disarmed the National Guard, a citizen’s militia that guarded the gates of Paris, and allowed the victorious Prussians to occupy Paris briefly. Resistance from revolutionaries supporting the National Guard forced Thiers to flee Paris forThe Fashoda Crisis of 1898 was born of the intense rivalry for European involvement in the “Scramble for Africa” (1881-1914). European powers, including Germany, Britain, France, ![]() Italy,

Italy, ![]() Portugal, and

Portugal, and ![]() Belgium, scrambled for control of territories, carving up Africa between them. While Germany pursued an incredibly aggressive colonialist agenda and claimed control of much of southwest Africa under Wilhelm II’s leadership and Belgium’s Leopold II ruthlessly claimed and exploited the Congo Free State, Britain and France engaged in an intense rivalry that was deeply at odds with the spirit of the entente. They squabbled over Britain’s occupation of Egypt, which began in 1882, and by 1898 they were engaged in fierce competition to claim the headwaters of the

Belgium, scrambled for control of territories, carving up Africa between them. While Germany pursued an incredibly aggressive colonialist agenda and claimed control of much of southwest Africa under Wilhelm II’s leadership and Belgium’s Leopold II ruthlessly claimed and exploited the Congo Free State, Britain and France engaged in an intense rivalry that was deeply at odds with the spirit of the entente. They squabbled over Britain’s occupation of Egypt, which began in 1882, and by 1898 they were engaged in fierce competition to claim the headwaters of the ![]() Nile, which would allow the victor to consolidate its holdings (France held territories that stretched along an east-west axis and included Senegal,

Nile, which would allow the victor to consolidate its holdings (France held territories that stretched along an east-west axis and included Senegal, ![]() Mali,

Mali, ![]() Niger, and

Niger, and ![]() Chad; Britain, however, controlled holdings that spanned a north-south axis and included modern-day South Africa,

Chad; Britain, however, controlled holdings that spanned a north-south axis and included modern-day South Africa, ![]() Botswana,

Botswana, ![]() Zimbabwe, and

Zimbabwe, and ![]() Zambia in Southern Africa as well as modern-day

Zambia in Southern Africa as well as modern-day ![]() Kenya in Eastern Africa.) In an effort to seize control of the Nile in 1898, French colonists arrived in Fashoda, a strategically important town in the South Sudan, only to be met with British gunboats. Tensions escalated, threatening the entente, and war seemed imminent. In the end, however, the French–led by the French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé–recognized the folly of engaging with the British (whose unsurpassed naval power trumped the size of the French army) and conceded defeat.

Kenya in Eastern Africa.) In an effort to seize control of the Nile in 1898, French colonists arrived in Fashoda, a strategically important town in the South Sudan, only to be met with British gunboats. Tensions escalated, threatening the entente, and war seemed imminent. In the end, however, the French–led by the French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé–recognized the folly of engaging with the British (whose unsurpassed naval power trumped the size of the French army) and conceded defeat.

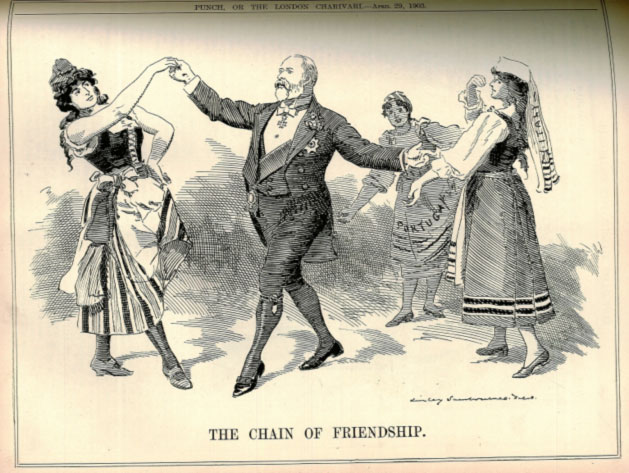

The defeat at Fashoda rankled the French, of course, but it also helped breathe new life into the entente as the French conceded the fact that an alliance with Britain was necessary. Indeed, Delcassé turned his attention to formalizing the entente, working with the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Lansdowne, and the French Ambassador to Britain, Paul Cambon, all of whom had labored behind the scenes to work out the intricacies of an agreement. Realizing that the entente would need public support if it were to survive, the heads of states, King Edward VII of England and French President Émile Loubet, arranged official visits to Paris and London, respectively. Two images published in Punch commemorated the state visits and underscored the tensions in Britain’s changing imperial relations. The first, an illustration titled, “The Chain of Friendship,” highlights the changes in imperial allegiances that Britain had to make to ensure the Entente would succeed. The illustration depicts Edward VII as he smoothly moves between his former imperial “friends,” Italy and Portugal–both of whom appear civilly to acquiesce to the change–to his new dance partner, the formidable-looking France. (See Fig. 5.)

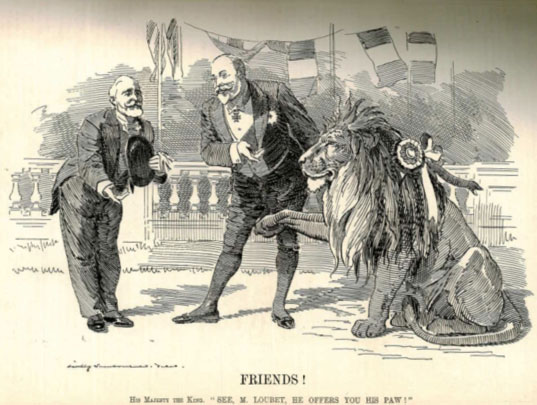

Later that same year, another illustration followed, this one simply titled “Friends!” in which Edward VII introduces Loubet to the English Lion on a parade ground festooned with the French Tricolor. (See Fig. 6.)

Like its predecessor, “Friends!” clearly promotes the civil spirit of mutual understanding of the entente: as the caption proclaims, the mannerly lion “offers” the French president his velveted paw. At the same time, however, “Friends!” also clearly highlights the imperial power dynamics. It is surely no mistake that Punch chose to represent England as the powerful, potentially menacing, figure of the Lion or that both Edward VII and the Lion dominate and isolate the figure of Loubet.

Although securing public support for the agreement was by no means a foregone conclusion, the efforts of both Edward VII and Loubet largely succeeded. As Punch archly remarked in May 1904, “The Entente continues to grow. A distinguished French journalist denies that the English are a Germanic race, and declares that the French are our real cousins. This must be Love” (“Charivaria” 329). Punch’s comment, of course, purposefully overstates the mutual affection between the English and the French, but, at the same time, it suggests that the official visits had drummed up enough public support for the Entente to move forward. A year later, British and French officials engaged in a flurry of tense last-minute negotiations that focused on contested territories and quibbled over language before officially signing and formalizing the Entente on 8 April 1904. The Entente immediately settled many of the lingering imperial issues that had been left unresolved after the Fashoda Crisis. Britain retained control of Egypt and gained fishing rights in ![]() Newfoundland. In exchange, France was given control of Morocco and granted territories near the border of Senegal and

Newfoundland. In exchange, France was given control of Morocco and granted territories near the border of Senegal and ![]() Gambia as well as in Nigeria.

Gambia as well as in Nigeria.

While the Entente did effectively settle key disputes at the policy level, the actual viability of the alliance it helped shape remained in question. Indeed, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II aggressively attempted to exploit the instability of the Entente and break it up in 1905 by challenging France’s control of Morocco. Germany’s bid to break up the Entente failed, however, when the British backed their new French allies. In the process, the deep divisions between Germany, on the one side, and Britain and France, on the other, had been revealed. It was in the spirit of the original entente cordiale, then, that, when the hounds of war were loosed in 1914, the British and French entered World War I as allies.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published December 2012

Embry, Kristi N. “The Entente cordiale between England and France, 8 April 1904.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bourne, Kenneth. The Foreign Policy of Victorian England, 1830-1902. Oxford: Clarendon, 1970. Print.

Bullen, R. J. Palmerston, Guizot, and the Collapse of the Entente Cordiale. London: Althlone, 1974. Print.

Bulwer-Lytton, Edward. England and the English. London: Bentley, 1833. Print.

Croker, John. The Croker Papers. New York: AMS, 1972. Print.

Dunham, Arthur Lewis. The Anglo-French Treaty of Commerce of 1860 and the Progress of the Industrial Revolution in France. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1930. Print.

“Editorial.” The London Times. 25 February 1860: 11. Print.

Marsh, Peter T. “The End of the Anglo-French Commercial Alliance, 1860-1904.” Anglo-French Relations 1898-1998: From Fashoda to Jospin. Ed. Philippe Chassaigne and Michael Dockrill. New York: Palgrave, 2002. 34-43. Print.

Marx, Karl. The Civil War in France: The Paris Commune. 2nd edition. New York: International Publishers, 1988. Print.

Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm. New York: Viking, 1960. Print.

“Mr Carlyle on the War.” The Pall Mall Gazette. 18 Nov. 1870. 2. Print.

Punch. “The ‘Boef Gras’ for Paris. 1871.” 4 March 1871. 87. Print.

—. “The Chain of Friendship.” 29 April 1903. 209. Print.

–. “Charivaria.” 11 May 1904. 329. Print.

—. “A French Lesson.” 8 April 1871. 141. Print.

—. “The French Porcupine.” 19 Feb. 1859. 75. Print.

—. “Friends!” 8 July 1903. 11. Print.

—. “The Red ‘Mokanna.’” 3 June 1871. 225. Print.

Rolo, P. J. V. Entente Cordiale: The Origins and Negotiations of the Anglo-French Agreements of 8 April 1904. London: Macmillan, 1969. Print.

ENDNOTES

[*] Parts of this essay have been previously published.

[1] For more on the Anglo-French Agreement of 1860s, see Arthur Lewis Dunham’s study, The Anglo-French Treaty of Commerce of 1860 and the Progress of the Industrial Revolution in France.

[2] Thomas Carlyle, for instance, publicly championed the Germans in an editorial in which he wrote, “That noble, patient, deep, pious, and solid Germany should be at length welded into a nation and become Queen of the Continent instead of vapouring, vain-glorious, gesticulating, quarrelsome, restless, and over-sensitive France, seems to me the hopefullest public fact that has occurred in my time” (qtd. in “Mr Carlyle on the War” 2).

[3] The Fashoda Crisis is much more complex than I can detail here. For a more detailed view of Fashoda and the role it played in shaping Anglo-French relations, see Anglo-French Relations 1898-1998: From Fashoda to Jospin.