Abstract

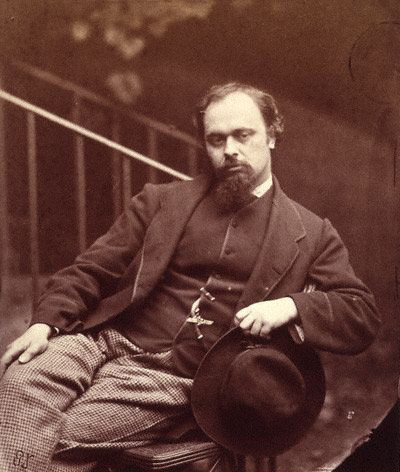

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s first volume of original poetry, by most accounts, comes at the close of two decades of Pre-Raphaelite experimentation, its 1870 publication a belated event. Yet it might as easily be taken as a sign of the future, particularly the renewed lyric inventiveness of fellow poets like William Morris, Algernon Swinburne, Christina Rossetti, George Meredith, and Gerard Manley Hopkins over the next several decades. Both the poetics and the material design of Rossetti’s 1870 volume were conceived to address crises of the moment and to show the way to a future for lyric, and especially for the lyric book. What would it mean to reverse our established scholarly perspective and read the event of Poems as its author might have hoped: in light of what followed?

This story is well known. In its usual version, the delayed appearance of Rossetti’s poems (some of them first conceived before 1850) makes Poems a belated event. (The fact that to prepare the volume Rossetti had an earlier manuscript exhumed from Elizabeth Siddall’s tomb—where he had buried it in a gesture of renunciation seven years earlier—is often cited to figure Poems as a morbidly posthumous event.) I’d like to suggest, however, that we might as easily see it as marking not an end but a beginning.[2]

Herbert Tucker, in his massive study of Victorian epic, describes 1868 as its annus mirabilis. Alfred Tennyson, Browning, and Morris each wrote the first installments of what, by Tucker’s account, became the major epic achievements of the high-Victorian period.[3] Tucker views 1868 prospectively as a year of promise and renewal for major poetry: three poets solved, freshly and differently, the challenge of reconciling the intensity of short poems with the demands of epic narrative ambition in what would become The Idylls of the King, The Ring and the Book, and The Earthly Paradise.[4] But these poetic events of 1868 (and the political events of 1867-71) sent other poets (and even some of the same poets) back to explore freshly the possibilities of the shorter lyric. By December of that year Rossetti had returned to poetry, selecting and rewriting old poems and composing new ones in a feverish burst of activity. Swinburne, who had just published his long essay on Blake (1868), was in constant correspondence with William Michael Rossetti on the latter’s edition of Shelley (1869), and would shortly begin both his own contributions to inspired political song in the radical tradition of those great predecessors (Songs Before Sunrise, 1871) and his experiment in sustaining lyric techniques across a longer poem, Tristram of Lyonesse.[5] Songs, like Poems, insisted that the way forward for English lyric should be not narrowly national but broadly European: the republican politics of an English poet expanded by immersion in the different cultural politics of Risorgimento ![]() Italy and republican

Italy and republican ![]() France. (For a BRANCH article on Risorgimento Italy, see Chapman, “On Il Risorgimento.”) His Songs made English lyric strange through the historical forms and political hopes of Greek, Provençal, Italian, and French verse. Tristram adopted the echoing weave of memory and metaphor Swinburne had first attempted in “Anactoria.” Condemning gods and kings, Swinburne’s Tristram, like his Sappho, celebrated a fearless mortality, while his prosodic modulations, extended over what would become thousands of singing lines, pushed readers’ memories to realize Sappho’s defiant claims that in lyric poetry’s future, always “Memories shall mix and metaphors of me” (“Anactoria,” line 214). Swinburne’s poetics of “long listening” were in part inspired by Richard Wagner’s radical methods of musical composition and by the paintings of his friend, Edward Burne-Jones, but grounded in his own mastery of lyric prosody in multiple linguistic traditions.[6]

France. (For a BRANCH article on Risorgimento Italy, see Chapman, “On Il Risorgimento.”) His Songs made English lyric strange through the historical forms and political hopes of Greek, Provençal, Italian, and French verse. Tristram adopted the echoing weave of memory and metaphor Swinburne had first attempted in “Anactoria.” Condemning gods and kings, Swinburne’s Tristram, like his Sappho, celebrated a fearless mortality, while his prosodic modulations, extended over what would become thousands of singing lines, pushed readers’ memories to realize Sappho’s defiant claims that in lyric poetry’s future, always “Memories shall mix and metaphors of me” (“Anactoria,” line 214). Swinburne’s poetics of “long listening” were in part inspired by Richard Wagner’s radical methods of musical composition and by the paintings of his friend, Edward Burne-Jones, but grounded in his own mastery of lyric prosody in multiple linguistic traditions.[6]

Nor was Swinburne alone in his energetic pursuit of lyric possibilities. Christina Rossetti, though she feared her inspiration failing (and was seriously ill for several years in the early 1870s), would unexpectedly find fresh stimulus, first in nursery song (Sing-Song, 1871) and later in the daily cycle of the Christian year and commentary on the apocalypse.[7] Pause and silence, in her minimalist poetics, orchestrate understatement, omission, and surprise to produce an edgy reworking of lyric’s debts both to the nursery and the cloister. Gerard Manley Hopkins set out to destroy what he had written in the 1860s when he became a Jesuit, but returned to write extraordinary new poetry in the late 1870s and 1880s. His sonnets and other lyrics were saturated in what he called “figures of sound”—embracing fully lyric’s auditory dimensions long after manuscript and print revolutions had supposedly rendered them obsolete (Hopkins 267). Anglo-Saxon, Greek, and Welsh prosody made strange the rhythms and rhymes of English to achieve what would appear—when his poetry was finally published in the twentieth century—startlingly modern. Morris, too, in the 1880s and 90s returned to lyric, but approached it now as a crucial location for exploring rhythm’s potential (as chant) to mobilize an imaginative experience of cross-temporal social fellowship. First in “Chants for Socialists” (1885) and later in the alliterative accentual verse, song-speech, charms, and riddles embedded in his prose romances of the 1890s, Morris turned to lyric’s embodied, performative potential for bearing and transforming collective cultural experience.[8] If 1868 was an annus mirabilis for epic, it was followed by a no less fruitful moment when poets turned, again but differently, to lyric. With renewed energies and fresh experimentation they found unexplored possibilities in the materiality of poetic language foregrounded through prosody (the affective “music” of verse), and in its physical forms, particularly the designed book.

Let me suggest what a story along those lines might look like: the story in which the publication of Poems in 1870 points toward several decades of re-invention for lyric’s matter—its subjects through its prosodic and material forms—without which the lyric achievements of poets as diverse as Hardy and William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, Charles Bernheimer and Barbara Guest, would be hard to imagine. Lyric, after all, was suffering a pervading sense of crisis. Lyric survival seemed to demand new modes both of writing and of presentation. Deflected from familiar forms or dissatisfied with their own earlier efforts, the younger poets (Rossetti and Swinburne and Morris, but also Christina Rossetti, George Meredith, and the unpublished Hopkins) were ready to strike out in new directions. Poems was meant to offer a way forward.

From a publishing perspective, the crisis was real. Original volumes of poetry were overshadowed by market-dominating novels; the epic achievements of 1868 were both a response and a further obstacle to lyric’s publishing survival. Rossetti’s practice offered one potential solution: designing books whose family resemblance might give them a collective identity in the public eye, signaling respect for style and craftsmanship in both its material and prosodic forms. Publishing might become a collective enterprise. Rossetti himself enlisted family and friends in the meticulous revising and arranging of Poems. He encouraged Morris and Christina to publish with his friend and publisher, F. S. Ellis. As if binding (literally) the new lyricism into a collaborative project of renewal, he involved himself deeply in the editing, arrangement, and physical design not only of his own books—The Early Italian Poets (1861) as well as Poems—but of his sister’s and Swinburne’s. He designed covers and frontispieces for Goblin Market and Other Poems (1862 and 1865) and The Prince’s Progress and Other Poems (1866), and commented extensively on the manuscript; for Swinburne he designed the covers for Atalanta in Calydon (1865) and Songs Before Sunrise (1871).[9]

Indeed, Rossetti attended obsessively to every detail of the design of Poems: the division into parts, the sequence of poems within each part, the alternating rhythms of ballad and song and sonnet designed to stretch a reader’s embodied imagination both formally and temporally; but also the arrangement of the poems on the page; the shape and proportions of page, type, and margins; the color and pattern of the endpapers. For Rossetti the book of lyric poems was itself envisioned as a coordinated auditory, visual, and conceptual experience for the reader, one with a semantic but also a semiotic material dimension. Rhythm and meaning, abstraction and intimacy, sound and image, page and poem: within these often hierarchically ordered pairs, each element would assert its presence in the experience offered by the book as a designed event.

Though Morris did not join Rossetti’s project, he certainly recognized its importance. He had originally planned The Earthly Paradise, an elaborate structure where lyrics introduced and punctuated a frame narrative enclosing verse tales with their own embedded song poems, to be visually as well as verbally innovative. Each double-page spread would present an architectural design of text, margin, and boldly printed black and white images, wood engravings from designs by Burne-Jones, his friend and collaborator. The Big Book, as Morris and Burne-Jones referred to it, was intended to be read aloud, its tales retold, as they were within the poem’s narrative frame, repairing damaged senses as well as spirits in a modern audience.[10] These plans were frustrated by the limitations of existing typefaces and commercial publishing, but in the next decades Morris continued to experiment: in the 1880s, with the inexpensive printing of mixed prose and poetry, political analysis, romance, and song in the socialist papers and pamphlets for which he wrote, edited, and served as financial support, particularly Commonweal. In the 1890s he began his most famous experiment with hand presses, high quality paper and inks, newly designed types and images for limited-edition, subscription printing at his own Kelmscott Press. There he produced physically beautiful books of both his own and others’ poetry, extending—for the many small presses which followed in the twentieth century and beyond—the possibilities for the poetic event of the book that he, like Rossetti, imagined in 1870 as lyric’s future.

The poetics of Poems are, however, as important signs of lyric’s future as are its physical forms. Friends and fellow poets (from whom Rossetti sought comments and suggestions at every stage while the new volume was being prepared) recognized at once the originality of Rossetti’s inventive adaptations of stanzaic forms and lyric kinds in the volume’s first part (“Poems”), singling out particularly the refrain ballads (“Sister Helen,” “Troy Town,” “Eden Bower”) and the dramatic monologues (especially “Jenny,” with its modern setting and daring subject). Critics in the last half-century have focused increasingly on his originality as a creator of picture-poems or double works of art, sonnets composed for his own and others’ pictures, collected together in the third of the volume’s three parts (“Sonnets for Pictures and Other Sonnets”).[11] Poems’ central section, “Sonnets and Songs Towards a Poem to Be Called the ‘House of Life,’” is both his most difficult and, in the poet’s own view, most innovative experiment. It turns away from the confessional or meditative personal lyric to recover the impersonality achieved through poetic form, while taking as lyric matter the shape of psychic life lived within the secular horizons of modernity. As its original title suggests, it is also where Rossetti called attention to sonic as well as visual design.

In part depersonalization is an effect of Rossetti’s unusual use of fictional personification: love gives birth to Love, which then engenders particularized scenes between nameless, representative lovers, identified only as “we,” “thou and I,” or “My Lady and I”— as in the sonnet that opened the 1870 sequence, “Bridal Birth,” for example; or later in the sequence, when “the lost days of my life” return as “Might-have-been,” “No-more, Too-late, Farewell”—personified Hours drawing imagination both backward to the pains and pleasures of love and forward toward death (and Death), as in “Lost Days,” “A Superscription,” and “Newborn Death”.[12] The turn to fictional personification involves a process of abstraction from personal experience, but what is surprising is that this abstraction is followed by imaginative projection into sensuously realized scenes that Love or “Might-have-been” can generate. Imaginative projection is the technique Rossetti called establishing an “inner standing point” and had earlier used to produce poems like “Ave,” “The Blessed Damozel” (where a nameless lover imagines the warmth of his dead beloved’s body, leaning towards him across heaven’s gates, and the sound of her tears), and his modern-life dramatic monologue, “Jenny,” as well as sonnets on paintings like “For a Venetian Pastoral, by Giorgione” and “For an Allegorical Dance of Women by Andrea Mantegna.” Taking up an inner standing point allows the poet to realize a painted, allegorized, or emblematically figured scene as if it were real by projecting himself into it as an embodied, perceiving presence. From there he sees, hears, and feels above, behind, and around the figures on a canvas or the fictions on a page, as if exploring in real time.

Such sensuous immediacy is matched and carried by the poem’s attention throughout to prosodic craft: the complex rhythmic patterns of sonic repetition and variation within and across lines, the dense texture of echoed vowels and consonants that set up their own patterns of culturally resonant association. (For Rossetti—as for his fellow younger lyric poets—this often meant bringing into English poetry the different sounds and rhythms of another language, as Pound was particularly to appreciate). In this way, too, the sonnets acquire their disconcerting combination of immediacy and distance. The immediacy of sensed experience is yoked to the historical distance and self-estrangement of personification. The materiality of language and its affects, especially the intimacy of sound and touch, gives bodily presence to fictionally figured sensations and feelings. The complex interiority so dramatized is recognizably that of a modern subject. Yet the shape and rhythms of the language (English small words, Latinate interjections; the pull toward syllabic verse within and against an accentual-syllabic rhythm; the Italian form of the sonnet with its visibly marked volta) are both familiar and culturally foreign or historically distant.[13] The poem’s larger forms, figural techniques, and much of its particular imagistic and verbal vocabulary deliberately recall the poetics, the politics, and the belief structures of the Catholic early Renaissance of Dante and the stil novisti. Temporal and linguistic perspectives are doubled. At the same time rhythms of thought alien to poetry—the patterned repetitions of visual or musical arts—introduce further strangeness in the heart of the familiar. While the subject of “The House of Life” is modern psychic life, that modernity is discovered in part through such encounters with nineteenth-century English modernity’s unexpected and unfamiliar others. “Now” is shadowed and brought into relief by “then”; poetry’s bodily, affective, and semiotic languages by those of painting and song.[14]

The “House of Life” in its 1870 version was a work in progress. Changes made between then and the version that appeared in 1881—in which the Songs were separated out into their own section of the volume and many new sonnets added—bring out more explicitly the bones of the long poem’s structures. The later version clarifies the intent of the 1870 poem: that the poetic event of “House of Life,” for readers as well as the poet, offers a chance to re-experience the emotional messiness of modern psychic life ordered into meaningful form in shared, yet also estranged, poetic language. Teleologies of science or religion or the promises of political and social progress fail to make sense of psychic pain and pleasure. Rossetti’s “vita nuova” is, like Dante’s, a new life both for and through poetry. The 1881 version (the last completed; Rossetti died the following year) is prefaced by an extra-sequential Sonnet on the Sonnet and divided into two parts that observe the proportions of the sonnet’s octave/sestet division (Rossetti almost always separates the two parts of his sonnets syntactically and typographically). Part 1 of the long poem begins with an ecstatic account of mutual love that darkens, first with the expectation and then the experience of its loss; Part 2 assumes a perspective past the mid-point of a life to look both backward at lost hours and forward to the advancing horizon of death. At what would be the turn or volta between Parts 1 and 2, Rossetti has inserted three new sonnets. “Love’s Last Gift,” which now closes “Love and Change,” announces that gift as Song, that ability to give shape and significance through poetic forms and prosody to what has occurred and to what is yet to come. “Transfigured Life” and “The Song-Throe,” which now open Part 2, “Change and Fate,” figuratively describe those poetic techniques of abstraction and imaginative re-embodiment by which lived personal experience can be trans-figured into poetic song. The turn of the poem, in other words, is marked by a recognition that “Change” is “Fate”: the poem’s formal inevitabilities endowing with significance as they now actively shape the life left to live.

In one sense, of course, the event of Poems, 1870, was followed only by Rossetti’s two volumes of 1881. The particular poetic form Rossetti offered in “The House of Life” as an interpretation of modern life was not taken up by others with his explanatory ambitions or his bold challenge to religious, philosophical, or political ways of shaping individual life. Rossetti also failed to persuade most of his fellow poets to join their works to his in material forms that would announce their common commitments to the fully-designed lyric book. Yet, both for poets, friendly and hostile, writing at the time and for those looking back from the perspective of the twentieth or the twenty-first centuries, Poems is still an astonishing event. Its belief in the power of the designed book, and its emphatic return to the material ground of poetry—its aural and visual rhythms, its culturally resonant forms—affirmed the related ambitions of poets as diverse in their practice (and, indeed, their beliefs) as Swinburne, Morris, Christina Rossetti, and Hopkins—but also Yeats, Pound, and our contemporaries. Prescient in its grasp of directions in which lyric might still be made to matter, it can stand as signpost to much of what was yet to come.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published October 2012

Helsinger, Elizabeth. “Lyric Poetry and the Event of Poems, 1870.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Dunlap, Joseph R. The Book That Never Was. New York: Oriole, 1971. Print.

Forrest-Thompson, Veronica. “Lilies from the Acorn.” Chicago Review 56.2/3 (2011): 36-47. Print.

Grieve, Alastair. “Rossetti’s Applied Art Designs—2: Book Bindings.” Burlington Magazine 115 (Feb. 1973): 79-84. Print.

Helsinger, Elizabeth K. Poetry and the Pre-Raphaelite Arts: Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris. New Haven: Yale UP, 2008. Print.

—. “Telling Time: Song’s Rhythms in Morris’s Late Lyrics.” William Morris and Social Change. Ed. Michelle Weinroth and Paul LeDuc Browne. Montreal: Queens-McGill UP, forthcoming 2013. Print.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “Rhythm and the Other Structural Parts of Rhetoric—Verse.” The Journals and Papers of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Ed. Humphrey House and Graham Storey. London: Oxford UP, 1959. 267-88. Print.

Leonard, Anne. “The Musical Imagination of Henri Fantin-Latour.” Rival Sisters: Art and Music at the Birth of Modernism, 1800-1900. Ed. James H. Rubin with Olivia Mattis.: Ashgate, forthcoming 2013. Print.

Maitland, Thomas [Robert Buchanan]. “The Fleshly School of Poetry – D. G. Rossetti.” The Contemporary Review 18 (Oct. 1871): 334-50. Print.

McGann, Jerome J. “A Commentary on Some of Rossetti’s Translations from Dante.” Haunted Texts: Studies in Pre-Raphaelitism. Ed. David Latham. Toronto: U of Toronto P. 35-52. Print.

—. Black Riders: The Visible Language of Modernism. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1993. Print.

—. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Game That Must Be Lost. New Haven: Yale UP, 2000. Print.

—. “Rossetti’s Iconic Page.” The Iconic Page in Manuscript, Print, and Digital Culture. Ed. George Bornstein and Theresa Tinkle. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1998.123-40. Print.

—. “Wagner, Baudelaire, Swinburne: Poetry in the Condition of Music.” Victorian Poetry 47.4 (2009): 619-32. Project Muse. Web. 6 June 2012.

Needham, Paul, Joseph Dunlap and John Dreyfus. William Morris and the Art of the Book. New York: The Pierpont Morgan Library/Oxford UP, 1976. Print.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Rossetti Archive: The Complete Writings and Pictures of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. A Hypermedia Archive. Ed. Jerome J. McGann. Web. 9 June 2012.

Saville, Julia F. “Cosmopolitan Republican Swinburne, the Immersive Poet as Public Moralist.” Victorian Poetry 47.4 (2009): 691-713. Project Muse. Web. 6 June 2012.

Skoblow, Jeffrey. Paradise Dislocated: Morris, Politics, and Art. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1993. Print.

Swinburne, Algernon Charles. Major Poems and Selected Prose. Ed. Jerome J. McGann and

Charles L. Sligh. New Haven: Yale UP, 2004. Print.

—. The Swinburne Letters (1869-1875). Ed. Cecil Y. Lang. Vol. 2. New Haven: Yale UP, 1959. Print.

Tucker, Herbert F. Epic: Britain’s Heroic Muse, 1790-1910. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

[1] Rossetti had published individual poems in various journals, beginning with the short-lived Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) periodical, The Germ (1850); in 1861 he published a volume of his translations, The Early Italian Poets. At that time he planned a companion volume of his own poetry, to be called Dante at Verona, and Other Poems; on the death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddall, in 1862, however, he gave up that project and turned to painting. In the fall of 1868 he began to assemble his poems once again, revising many and composing new ones. For the composition and publication history of Rossetti’s poetic projects, see the Rossetti Archive.

[2] In Herbert Tucker’s terms, this would be to read the event as advent; see Tucker, “In the Event of a Second Reform.” As I hope will be evident, I’m not here making the argument for specific influences but rather proposing that we adjust our sense of Rossetti’s 1870 volume to recognize differently its signifying potential for the stories we tell about Victorian and modern poetry, particularly with respect to the work of a diverse group of younger poets who shared his conviction that lyric “thinks” through prosodic and material form.

[3]> Tucker describes the 1860s as “Victorian epic’s finest hour” (Epic, 386), “the most intensively epical of Victoria’s reign” (390), whose annus mirabilis was 1868 (391, 448). George Eliot’s one long narrative poem, The Scholar Gypsy, also appeared in the same year.

[4] In his essay “In the Event of a Second Reform,” Tucker connects this turn to national epic with the transformation of the English electorate (beginning with the passage of the Second Reform Bill in 1867)—and with it, the urgent problem of re-conceiving the nation for an expanded reading and voting citizenry. In 1869 Tennyson published “The Holy Grail,” which had occupied him the preceding year; it was the crucial step toward transforming into an epic narrative the two contrasting pairs of idylls published in 1859 and his earlier “La Morte d’Arthur.” By 1873 the architecture and most of the parts were in place, though the final version of The Idylls of the King did not appear until 1886. Parts 1 and 2 of Morris’s The Earthly Paradise were published in 1868, parts 3 and 4 in 1870. The first installments of Browning’s The Ring and the Book appeared in 1868, the completed poem in 1869.

[5] The Prelude to Tristram appeared in 1871; the completed poem was not published until 1886, though Swinburne was well along in its conception by 1870. In many ways written against Tennyson’s Arthurian epic and its more narrowly national concerns, Tristram and Songs Before Sunrise are deeply European in inspiration, both poetically and politically. (Songs was dedicated to Mazzini and the Italian Risorgimento; it was also written in the shadow of Louis Napoleon’s Second Empire in France, whose downfall to the short-lived Republic in 1871 confirmed Swinburne’s own self-identification with international struggles against monarchy, empire, and the Church.) The early 1870s were rather the beginning than the close of Swinburne’s still under-appreciated lyric achievement. On Swinburne’s political song, see Saville, “Cosmopolitan Republican Swinburne.”

[6] Writing to his close friend, the painter Edward Burne-Jones, about his plans for Tristram, Swinburne acknowledged, “the thought of your painting and Wagner’s music ought to abash but does stimulate me” (Swinburne’s Letters, 2.51). For more on Wagner’s role in Swinburne’s ideas about musical prosody, see McGann, “Wagner, Baudelaire, Swinburne.” I take the phrase “long listening”—designating the prolonged attentiveness that the new music of Wagner required—from Leonard, “The Musical Imagination of Henri Fantin-Latour.”

[7] Rossetti first inserted three poems into her prose collection for children, Commonplace and Other Stories (1870). The title poem of A Pageant and Other Poems (1881) is a verse play for children. Time Flies (1885) and The Face of the Deep (1892) find homes for lyric within meditative prose. Less directly, the biblical commentaries and prose meditations for daily prayer also supported Rossetti’s two major sonnet sequences, “Monna Innominata” and “Later Life,” both published in Pageant. The lyrics composed for Time Flies and The Face of the Deep, with others written for Called to be Saints (1881), were later collected in her last publication, Verses (1893).

[8] Helsinger, “Telling Time.” Morris also continued to direct much energy to epic (and, of course, to wallpapers, weaving, prose romance, and a multitude of other lesser and greater arts). His Icelandic-inspired Sigurd the Volsung (1876) is probably his most impressive original epic, but over the next decades he undertook verse translations of the Aeneid (1875), The Odyssey (1887), and Beowulf (1895).

[9] Rossetti helped make at least eight books in the ten-year period between 1861 and 1871. In addition to the books mentioned above, he designed covers for his brother William’s translation of Dante’s Inferno (1865), and his sister Maria’s commentary on Dante (1871). While the individual designs differ, some of Rossetti’s aesthetic preferences—for wrap-around design and (in several striking cases) a Japanese-influenced simplicity and asymmetry—give his design projects a family resemblance (several also use the same binding color). Rossetti was pleased when, at his urging, Christina (for her prose stories) and Morris (in two of his books published 1870-3), adopted Ellis as publisher. On Rossetti’s book designs, see Grieve, “Rossetti’s Applied Art Designs—2: Book Bindings”; McGann, “Rossetti’s Iconic Page”; and my Poetry and The Pre-Raphaelite Arts (175-98).

[10] On Morris’s pre-Kelmscott book designing projects, see Dunlap, The Book That Never Was; Needham, Dunlap, and Dreyfus, William Morris and the Art of the Book; McGann, Black Riders (45-75); Skoblow, Paradise Dislocated; and Helsinger, Poetry and the Pre-Raphaelite Arts (199-217).

[11] Probably the single most influential recent critical study of Rossetti is McGann, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Game That Must Be Lost. See also his critical commentary to the poems in the Rossetti Archive.

[12] Forrest-Thompson’s “Lilies from the Acorn” has an intriguing discussion of Rossetti’s use of personification (which she calls allegory). See also McGann’s commentaries in the Rossetti Archive and Helsinger, Poetry and the Pre-Raphaelite Arts (218-57) on the poetics of “The House of Life.”

[13] See McGann, “A Commentary on Some of Rossetti’s Translations from Dante,” and Helsinger, Poetry (246-55).

[14] In both the first and last sections of the 1870 volume Rossetti has explored more fully the imaginative worlds that shadow the exploration of modern psychic life in the volume’s central section: in, for example, “Dante at Verona” (Dante as poet and political exile) or “Ave” (the Virgin of early Renaissance painting and Christian belief).