Abstract

Andrew Iredale welcomed Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria and her cousins to his library in Toquay, Devon on 1 September 1898 where the group bought books and photographs. Founded by Iredale in 1872, Iredale’s Library became the “centre of literary life” in the seaside resort community well into the twentieth century. This article considers the circulating library’s role in the community: in addition to selling and lending books, the library served as a place for public and private meetings, third-party business transactions, and interpersonal networking. As the history of Iredale’s Library illustrates, provincial circulating libraries played a vital role in communities well beyond their money-making operations.

I. The Princess and the Librarian

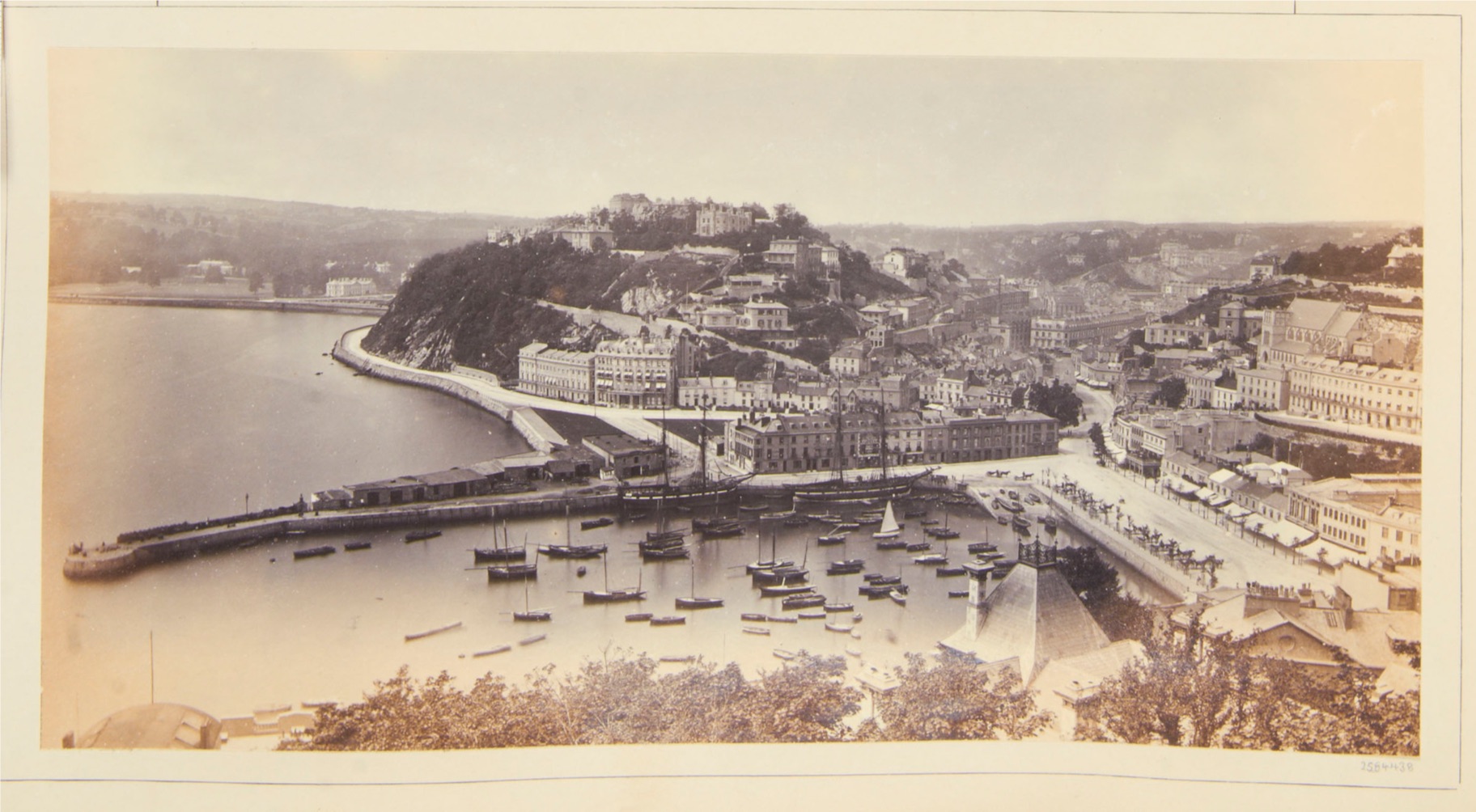

On the early morning of Thursday, 1 September 1898, the royal yacht Osborne steamed into ![]() Torquay bay carrying H. R. H. the Prince of Wales, his daughter Princess Victoria, his nephew Prince Nicholas of Greece, and his niece Princess Marie of Greece. The local newspaper, The Torquay Times, covered their visit in minute detail: while the Prince of Wales remained on board the yacht, at ten o’clock, the younger members of the party embarked on a visit to the fashionable seaside town.[1] Armed with her hand camera, Princess Victoria and her cousins visited the Princess Gardens (named for her aunt, Princess Louise) before walking down Cary Parade where they engaged a cab and drove north along Babbacombe Road. They paused their drive to walk along the beach at Anstey’s Cove, “where they remained chattering in a foreign language and admiring the beautiful scenery … for a considerable time,” according to the newspaper account. Driven back to town, the royal party dismissed the cab and walked along the Strand, “frequently stopping to look in the shops’ windows,” and they made purchases at two establishments. After their shopping, the group again visited the Princess Gardens, where they sat overlooking the fountain, but in the meantime they attracted a growing crowd of curious townspeople, which eventually became “rather uncomfortable” for the royal visitors. After a short time, the royal party walked down to the pier, entered the waiting launch, and returned to the yacht. By one o’clock, the yacht hoisted anchor and left the bay sailing eastward. In all, the royal visit lasted less than six hours; the shore party less than three hours.

Torquay bay carrying H. R. H. the Prince of Wales, his daughter Princess Victoria, his nephew Prince Nicholas of Greece, and his niece Princess Marie of Greece. The local newspaper, The Torquay Times, covered their visit in minute detail: while the Prince of Wales remained on board the yacht, at ten o’clock, the younger members of the party embarked on a visit to the fashionable seaside town.[1] Armed with her hand camera, Princess Victoria and her cousins visited the Princess Gardens (named for her aunt, Princess Louise) before walking down Cary Parade where they engaged a cab and drove north along Babbacombe Road. They paused their drive to walk along the beach at Anstey’s Cove, “where they remained chattering in a foreign language and admiring the beautiful scenery … for a considerable time,” according to the newspaper account. Driven back to town, the royal party dismissed the cab and walked along the Strand, “frequently stopping to look in the shops’ windows,” and they made purchases at two establishments. After their shopping, the group again visited the Princess Gardens, where they sat overlooking the fountain, but in the meantime they attracted a growing crowd of curious townspeople, which eventually became “rather uncomfortable” for the royal visitors. After a short time, the royal party walked down to the pier, entered the waiting launch, and returned to the yacht. By one o’clock, the yacht hoisted anchor and left the bay sailing eastward. In all, the royal visit lasted less than six hours; the shore party less than three hours.

Perhaps there is nothing too remarkable about this rather short visit of royalty to a seaside town, except that the itinerary of their brief excursion included an extended stop at Iredale’s Library on the Strand, one of the two named businesses in the article patronized by the royal party. In fact, The Torquay Times‘s article describing the royal visit affords a prominent subheading and over a third of its column space to recounting the royals’ visit to the library (in comparison, their visit to R. T. Knight’s drapery business sadly elicits no further comment). On entering the library, they were received by the owner himself, Andrew Iredale, and the “distinguished visitors seemed impressed with the extent of the premises and the numerous resources of the business.” In particular, Princess Victoria, a keen photographer like her mother, Princess Alexandra, gravitated to Iredale’s large collection of photographs, especially those of yachts, dogs, and hunting scenes, “of which Her Royal Highness made several purchases.” The article goes on to note, “Others of the party also bought souvenirs of their visit and some of the most recently published books.” Iredale conducted their tour of the various departments on the ground floor before inviting them upstairs to the gallery to inspect a series of battle paintings and prints by Richard Caton Woodville, including his rendition of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and his “equally interesting pictures of the battle of ![]() Alma and of

Alma and of ![]() Sebastopol,” in which the party spent time attempting to identify the depicted officers. Then,

Sebastopol,” in which the party spent time attempting to identify the depicted officers. Then,

In the course of conversation with Mr. Iredale, the Princess referred in appreciative terms to her last visit to Torquay, in 1886, when she, along with her mother… and the Princess Maud, were the guests of the Duchess of Sutherland at Sutherland Tower. In the words of H. R. H., in the death of the Duchess we suffered “a great loss.” “Who lives there now?” she inquired, and was informed by Mr. Iredale that Miss Aldam was the present tenant.[2]

While the princess and the librarian conversed (dare we say “gossiped”?), Sir Francis Knollys, the Prince of Wales’ equerry, entered the library: as the article notes, Sir Francis had “been a customer in former times, and he came to make inquiries in the second-hand department for books which he required.” The tour ended with the royal party “severally inscrib[ing] their names in Mr. Iredale’s visitors’ book, greatly enhancing a collection which already includes the signatures of persons of rank, and men and women holding high positions in literature, science and art.”

The newspaper article in The Torquay Times clearly identifies the royal visit to Iredale’s Library as an important, if not the leading, event in their excursion to the town. In a like way, the librarian’s visitors’ book attests to the upper social range of his customers and suggests his royal visitors join a long line of distinguished customers. But, what seems most charming and striking about the newspaper coverage of the royal visit is the importance it assumes about Iredale’s Library itself as a centerpiece of the town. That a library, let alone any business, should occupy such a prominent place in a Victorian town or city is the subject of this paper. In the present, we take for granted that public libraries often serve multiple purposes and provide diverse services. In the Victorian period, however, before the proliferation of public libraries such as the rate-supported Torquay public library commenced in 1907, most provincial libraries were private businesses or private institutions. What I would like to argue is that circulating libraries, private businesses, or institutions that charged subscriptions to borrow books often served larger public functions in their communities beyond that of simply distributing books. Using Iredale’s Library in Torquay as the main example, this article hopes to elucidate these larger public functions that Iredale’s and other provincial circulating libraries provided to their communities. If we want to better understand readers and the material culture of reading during the Victorian period, then we must investigate the roles of circulating libraries in provincial life.

II. Victorian Circulating Libraries

Iredale’s Library in Torquay was just one of hundreds, if not thousands, of circulating libraries in existence during the Victorian period; Robin Alston’s Library History Database (2006) refers to over 30,000 libraries in Great Britain before 1850. The great variety of libraries, as Alston remarks, is “extraordinary,” and he finds some provision of print in almost every market town by 1820 and in many smaller villages by 1850: “libraries devoted to the arts and sciences; libraries in the workplace; libraries on omnibuses; libraries in inns; libraries on the estates of wealthy landowners provided for the workers; libraries associated with every type of society; village libraries provided by benevolent pastors.”[3] And, we should add, circulating libraries likewise flourished in the nineteenth century. By the turn of the nineteenth century several famous London circulating libraries, notably Hookham’s Circulating Library (founded 1764) and the Minerva Library (founded 1775), were already in operation. Within two decades, such businesses became ubiquitous beyond even the largest cities—as the several passing references to provincial circulating libraries in Jane Austen’s novels attest. For the Victorian period, two London circulating libraries attained nation-wide importance: Mudie’s Select Library founded in 1842 and W. H. Smith and Son’s Subscription Library founded in 1860.[4] By the 1880s, both Mudie’s and Smith’s had established branch operations and were distributing books far and wide, well beyond London. In the case of Mudie’s, the library offered to ship books within England or without for customers not located near a physical library. In the case of Smith’s, the library established branches in the hundreds of railway stations where it held news agent contracts.

But, as Alston enumerates, hundreds of other libraries existed in the shadow of Mudie’s Select Library and W. H. Smith and Son’s Subscription Library. Other libraries in and around London included, for example: Cawthorn and Hutt’s British Library in Cockspur Street (1795–1914), Chiswick Library in the High Road, Chiswick (c.1870s–1880s), Day’s Library (later called Rice’s Library) in Mount Street (1784–1957), Grosvenor Gallery Library in New Bond Street (later South Molton Street) (1880–c.1906), and Scholl’s Circulating Library on Kennington Road (c. 1860s). Outside of London, examples such as Lovejoy’s Library in ![]() Reading (1818–1928), Sutton’s Circulating Library in

Reading (1818–1928), Sutton’s Circulating Library in ![]() Fareham (c. 1840s–c. 1890s), James A. Acock’s Subscription Circulating Library in Oxford (c.1870s), Bentley’s Library in Castle Cary, Somersetshire (c.1880s), and H. C. Copson’s Circulating Library in Lowesmoor, Worcestershire (c.1880s) give a sense of the range and variety of subscription libraries.[5] Outside of England, circulating libraries existed in nearly every city or large town in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Both Mudie’s and Smith’s offered a service to provide books to provincial libraries for a price—for instance, the labels for both the Sutton’s Circulating Library and the Chiswick Library report “in connection with Mudie’s,” suggesting two such partnerships. In addition, many smaller libraries purchased the used copies of books from the larger libraries. Each of these libraries marked their books with printed labels—in the case of Mudie’s, distinctive bright yellow labels on the cover of each volume; in the case of Smith’s, more discreet purple labels on the endpapers. On the rare book market, it is not uncommon to find a nineteenth-century book with circulating library labels and some with multiple labels, one pasted on top of the other, as it passed from library to library and owner to owner.

Fareham (c. 1840s–c. 1890s), James A. Acock’s Subscription Circulating Library in Oxford (c.1870s), Bentley’s Library in Castle Cary, Somersetshire (c.1880s), and H. C. Copson’s Circulating Library in Lowesmoor, Worcestershire (c.1880s) give a sense of the range and variety of subscription libraries.[5] Outside of England, circulating libraries existed in nearly every city or large town in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Both Mudie’s and Smith’s offered a service to provide books to provincial libraries for a price—for instance, the labels for both the Sutton’s Circulating Library and the Chiswick Library report “in connection with Mudie’s,” suggesting two such partnerships. In addition, many smaller libraries purchased the used copies of books from the larger libraries. Each of these libraries marked their books with printed labels—in the case of Mudie’s, distinctive bright yellow labels on the cover of each volume; in the case of Smith’s, more discreet purple labels on the endpapers. On the rare book market, it is not uncommon to find a nineteenth-century book with circulating library labels and some with multiple labels, one pasted on top of the other, as it passed from library to library and owner to owner.

For literary scholars of the Victorian period, Mudie’s and Smith’s circulating libraries garner nearly all the attention, each the subject of articles, books, and chapters, due mainly to their size and location amid the London-centric publishing industry. Therefore few, if any, of these smaller circulating libraries figure in our contemporary scholarship.[6] The reason is all too clear: the records of these businesses invariably fail to survive—in fact, no business records of Mudie’s survive and only a few accounting ledgers of Smith’s survive. Going even further, few archival or print references of any kind often survive; and even fewer contemporary accounts—autobiographies, histories, interviews, or memoirs—were created, let alone survive. Hence, Mudie’s and Smith’s circulating libraries serve as a synecdoche of the whole population of libraries simply because some historical record of their operations persist to our present. Often what remains of a Victorian circulating library, as Alston observed, is simply a name and a place (as the list above illustrates), whether a fleeting reference in a guide-book or directory, the existence of a lone print catalogue, or the remains of a library’s label on an old book. The section that follows is a research experiment to re-construct the history of a provincial circulating library starting with simply a name and place: Iredale’s Library of Torquay, Devon.

III. Iredale’s Library

First, the place. The town of Torquay lies on the south coast of England situated about halfway between Exeter to the north and Plymouth to the south. Due to its mild climate, the town became a convalescent retreat in the early nineteenth century; with the development of the railways (notably the Great Western Railway), the town became a fashionable summer resort by late century. In 1891, the Torquay subdivision of the census listed 35,842 persons. Second, the name. “Iredale” elicits no results in the MLA International Bibliography or other full-text research databases such as Project Muse—as far as can be determined, no scholarly references have ever been made about this library. Google Books proves more useful: the name “Iredale” pops up in several nineteenth-century books and magazines. In particular, turn-of-the-century guide-books and directories invariably list Iredale’s Library: for instance, Pearson’s Gossipy Guide to South Devon (1902) calls the business “a social place of meeting and a very well arranged reading-room and library” (10). Trade magazines, such as The Bookseller and the Publishers’ Circular, include several references to Iredale and his library. Digitized collections of newspapers, however, produce the greatest results: most fortunately, the British Newspaper Archive includes The Torquay Times (begun in 1869), which includes hundreds of references to Iredale and his library (of which most are his advertisements), though other newspapers, both local and otherwise, make periodic references to Iredale. Finally, the Torquay Public Library has a few minor items of interest related to Iredale. Other archives and libraries prove fruitless—seemingly, no business or historical documents survive. Hence, in the absence of any business records, correspondence, history, or memoir, only a modest collection of sources about Iredale’s Library can be compiled, enough at least to piece together a general history of it.

Without a doubt, Andrew Iredale seems an unlikely candidate for becoming a prominent bookseller and librarian in Torquay.[7] He was born in Huddersfield, ![]() Yorkshire in 1840. As a young man he entered journalism, serving an apprenticeship on the staff of the Huddersfield Chronicle before joining the staff of the Leeds Mercury in 1861 on the cusp of it becoming the first daily newspaper in Yorkshire. In 1869, his pulmonary health began to fail and his doctors advised him to move to a warmer climate, suggesting either Australia or Torquay. As one biographical source relates, Iredale “chose the lesser evil” and moved with his young family to Torquay, where his health rapidly improved (Gerring 80). In 1872, he started as a second-hand bookseller in his adopted town and the business expanded rapidly, necessitating moves to larger premises in 1874 and 1888—the later location being a substantially large building at 13, the Strand. A guide-book in 1900 describes the Yorkshireman’s business this way:

Yorkshire in 1840. As a young man he entered journalism, serving an apprenticeship on the staff of the Huddersfield Chronicle before joining the staff of the Leeds Mercury in 1861 on the cusp of it becoming the first daily newspaper in Yorkshire. In 1869, his pulmonary health began to fail and his doctors advised him to move to a warmer climate, suggesting either Australia or Torquay. As one biographical source relates, Iredale “chose the lesser evil” and moved with his young family to Torquay, where his health rapidly improved (Gerring 80). In 1872, he started as a second-hand bookseller in his adopted town and the business expanded rapidly, necessitating moves to larger premises in 1874 and 1888—the later location being a substantially large building at 13, the Strand. A guide-book in 1900 describes the Yorkshireman’s business this way:

Mr. Iredale now conducts a gigantic business. Besides books, new and old, to the number of 50,000 volumes, the departments include stationary and fancy goods, etchings, engravings, and water colours; and he has added a very large “Subscription Library,” from which books are delivered by van to a distance of ten miles around. He has fitted up [two] luxurious reading rooms for ladies and gentlemen, a spacious smoking room has been provided, in fact nothing has been overlooked for readers’ and customers’ convenience. (Gerring 81)

In fact, the two reading rooms overlooked the bandstand on the Strand where the Royal Italian Band performed each day. Numerous other sources describe the premises on the Strand as impressive and grand. Iredale eventually added a branch operation down the west coast in neighboring ![]() Paignton. In 1900, Iredale visited

Paignton. In 1900, Iredale visited ![]() America and on his return wrote a travel book, An Autumn Tour in the United States and Canada (self-published in 1901). His eldest son, George Herbert Iredale (b. 1863), joined the business and gradually took over the day-to-day operation. (He also had another son, who entered the army, and a daughter.) Both father and son became active in local and national affairs. In particular, Andrew Iredale was a member of the elected

America and on his return wrote a travel book, An Autumn Tour in the United States and Canada (self-published in 1901). His eldest son, George Herbert Iredale (b. 1863), joined the business and gradually took over the day-to-day operation. (He also had another son, who entered the army, and a daughter.) Both father and son became active in local and national affairs. In particular, Andrew Iredale was a member of the elected ![]() Devon County Council, the Council of the Associated Booksellers of Great Britain and Ireland, and numerous local business and civic boards. George Iredale was a member of the town council, served as the mayor of Torquay, led local public commissions (in education, energy, and transportation), and joined several local philanthropic and sporting societies. The family business continued until 1921 when the premises were sold. Andrew Iredale suffered a paralytic attack in 1922 and died two years later. His son George died in 1942.

Devon County Council, the Council of the Associated Booksellers of Great Britain and Ireland, and numerous local business and civic boards. George Iredale was a member of the town council, served as the mayor of Torquay, led local public commissions (in education, energy, and transportation), and joined several local philanthropic and sporting societies. The family business continued until 1921 when the premises were sold. Andrew Iredale suffered a paralytic attack in 1922 and died two years later. His son George died in 1942.

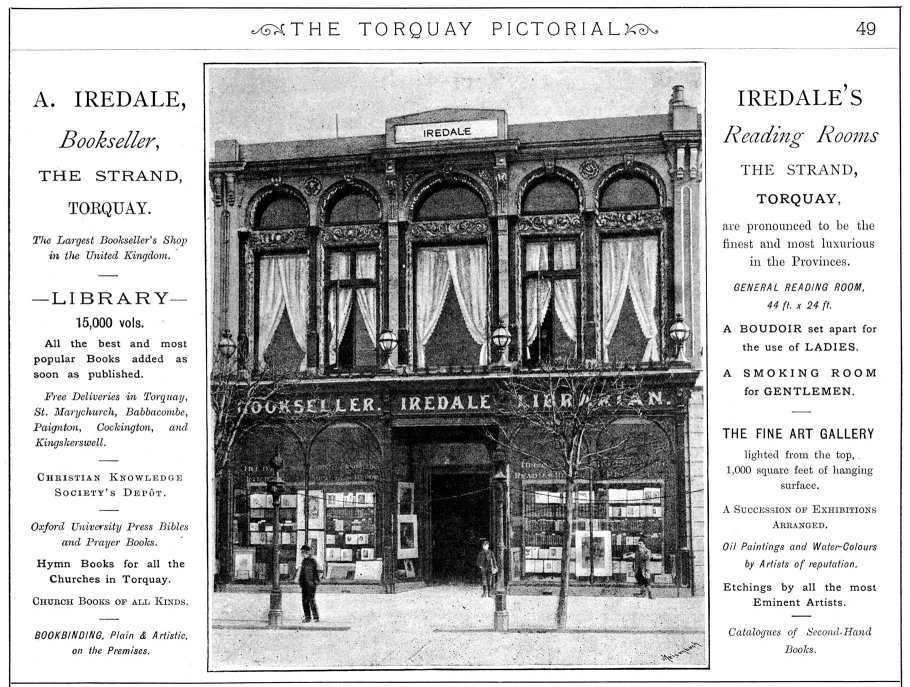

In all, Iredale’s business encompassed several related departments. First and foremost, Iredale was a bookseller of both new and used books, claiming in his advertisements to be “the largest Bookseller’s Shop in the United Kingdom” (Advertisement for Iredale’s Library 49). This may be a hyperbolic claim, but at least some contemporary visitors lend it some credit. For one, the author of the newspaper article “An Hour at Iredale’s Library” (1893) effuses, “No one can enter his emporium of knowledge without being struck by the long vista of books—neatly arranged upon shelves extending from floor to ceiling—stretching away into distance, that immediately confronts his view,” some 50,000 volumes in total (8). His used books sales extended to rare and antiquarian stock as evidenced by the numerous catalogues he issued over the years. Second, Iredale maintained a thriving subscription library of considerable size: as the same article notes, the new catalogue of the subscription library contained 15,000 titles in December 1893 and itself sold sixty copies in a week. During the “reading season” from the beginning of October to the end of April, the library reported sending out an average of 400 books each day: “Torquay, of course, makes that greatest demand upon [the library], but [neighboring] ![]() Babbacombe,

Babbacombe, ![]() St. Marychurch,

St. Marychurch, ![]() Cockington, Paignton,

Cockington, Paignton, ![]() Brixham,

Brixham, ![]() Dartmouth, and

Dartmouth, and ![]() Totnes come to Iredale’s Library for their reading, whilst in remote parts of Devon and

Totnes come to Iredale’s Library for their reading, whilst in remote parts of Devon and ![]() Cornwall there are regular subscribers who receive their books by post and rail,” notably owing to the development of the Great Western Railway (“An Hour at Iredale’s Library” 8). In fact, during the journalist’s visit, the librarians were packaging up books for shipping to

Cornwall there are regular subscribers who receive their books by post and rail,” notably owing to the development of the Great Western Railway (“An Hour at Iredale’s Library” 8). In fact, during the journalist’s visit, the librarians were packaging up books for shipping to ![]() Newton Abbot (a town some seven miles away), and he watched as “volumes are being selected and entered upon the subscribers’ cards, preparatory to their dispatch by the delivery van” (“An Hour at Iredale’s Library” 8). Iredale’s advertisements note that in town and in many nearby communities such deliveries were free of charge to subscribers. Third, Iredale converted part of the second floor of his larger premises into a fine art gallery, which his advertisements described as “lighted from the top, [with] 1,000 square feet of hanging surface” (Advertisement for Iredale’s Library 49). As we saw with Princess Victoria’s visit, Iredale’s Library frequently hosted exhibitions by notable artists of the day. Fourth, Iredale published books on his own account, mostly books by local authors or of local interest, including botany, guide-books, maps, and poetry. Finally, Iredale’s Library offered various other products and services, including bookbinding, stationary, and sundries. Lest one think that Iredale’s Library is an exceptional outlier, it practiced what most contemporary circulating libraries of the period did by incorporating multiple, related businesses under one roof. (Recall that the subscription library represented only a relatively small part of W. H. Smith’s overall business.)

Newton Abbot (a town some seven miles away), and he watched as “volumes are being selected and entered upon the subscribers’ cards, preparatory to their dispatch by the delivery van” (“An Hour at Iredale’s Library” 8). Iredale’s advertisements note that in town and in many nearby communities such deliveries were free of charge to subscribers. Third, Iredale converted part of the second floor of his larger premises into a fine art gallery, which his advertisements described as “lighted from the top, [with] 1,000 square feet of hanging surface” (Advertisement for Iredale’s Library 49). As we saw with Princess Victoria’s visit, Iredale’s Library frequently hosted exhibitions by notable artists of the day. Fourth, Iredale published books on his own account, mostly books by local authors or of local interest, including botany, guide-books, maps, and poetry. Finally, Iredale’s Library offered various other products and services, including bookbinding, stationary, and sundries. Lest one think that Iredale’s Library is an exceptional outlier, it practiced what most contemporary circulating libraries of the period did by incorporating multiple, related businesses under one roof. (Recall that the subscription library represented only a relatively small part of W. H. Smith’s overall business.)

The building itself, at 13, the Strand, faced the harbor and was described as the “finest business premises in the town” when Iredale took it over in 1888.[8] As noted earlier, the larger premises allowed Iredale to divide the space into various departments as well as create other public spaces, including a large public reading room “from the windows of which will be obtainable an uninterrupted view of the harbor and bay” and several smaller meeting rooms according to a Torquay Times article heralding the move. The building itself measured 44 feet in breadth by 175 feet in depth, which substantiated the library’s claim to be “the largest bookseller’s shop in the country” where “the fully stocked bookshelves, extending to many thousands of feet, with their light and elegant casing of pitch pine, present a really imposing appearance.” The decorated iron pillars and ornamental girders supporting the first floor were French grey and chocolate in color and “harmonize well with the bright pitch pine casing of the bookshelves and the other fixtures.” The article goes on to say that “the bookshelves have been brought forward from the outer walls, about eighteen inches, and in the intervening spaces are hot water pipes, with which the whole premises are warmed.” The first floor held the general reading room (measuring 44 feet by 24 feet), a boudoir “set apart for the use of Ladies,” a smoking room “for Gentlemen,” a lecture and assembly room, and the fine art gallery (“Mr. Iredale’s Reading Rooms” 8). The latter was octagonal in shape, lit naturally by an extensive glazed roof, and included 1,000 square feet of hanging surface. When the art gallery finally opened in 1890, an article in The Torquay Times opined that “Mr. Iredale’s establishment on the Strand bids fair to become the centre of the artistic as it is already the centre of the literary life” of the town (“Mr. Iredale’s New Art Gallery” 6). The store front of the building consisted of an imposing doorway and two rows of arched windows: those on the lower level displaying books and prints for sale; those on the upper level with visible readers behind graceful curtains. As situated, any visitor arriving in town via the harbor would first see Iredale’s Library on the Strand.

IV. The Role of Iredale’s Library in Torquay Life

Iredale’s Library, however, was more than a private business. As the reporter in The Torquay Times off-handedly states, the library already occupied “the centre of the literary life” of Torquay by 1890 (“Mr. Iredale’s New Art Gallery” 6). The local newspapers chronicle all the myriad ways the community of Torquay used and interacted through the library.

First and foremost, the library sold and lent books. Unfortunately, neither Iredale or his ordinary customers left records of the purchases or borrowings at the library, but several more famous names record their visits. The Cornish author Arthur Quiller-Couch (better known as “Q”) attended Newton Abbot College as a youth and recalls in his memoir, Memories and Opinions (1944), spending “a half-holiday at Torquay and…coming back in some glee nursing a first edition of The Bab Ballads (bought for 6d in Mr. Iredale’s bookshop)” (49). Editor and novelist Edmund Yates spent a winter holiday in Torquay in 1891, and he found the “most frequented resort [to be] Iredale’s Library, which is one of the best public establishments I have ever come across, with a very large collection of books, both for hire and sale” (7). The novelist Gordon Stables visited the library daily during a winter holiday spent in Torquay: as a journalist wrote of his visit, Stables “look[ed] appreciatively on the shelves upon shelves of books, and here and there recognizes the titles of well-known works, with which he is familiar, and chats with Mr. Iredale upon publishers and publishing” (“Chats with a Bookmaker” 8). Iredale’s librarian, William Roberts (later a journalist), writes in a reminiscence that the library “became the rendezvous of all who were of quality in literature and art in both Devon and Cornwall” (4). In fact, a number of authors lived in or around Torquay and frequented the library; as Roberts enumerates,

These included Miss Annie Drury, a kindly old lady, who lived at the top of Mill Lane, Torre; Miss Christabel Coleridge, co-editress with Charlotte M. Yonge of the “Monthly Packet” and Superintendent of Torre Sunday School; Miss [Frances Mary] Peard, who lived in the Croft Road for many years and was the much-loved centre of many friends; the Misses Jane and Helen Findlater and W. E. Norris who used to be called “the modern Thackeray,” but I never could understand why! … Then, too, came Eden Phillpotts—I think it was in 1900—and established himself at Eltham, Oakhill Road. (4)

To his list we could add the novelists Margaret Fairless Barber, Sabine Baring-Gould, Quiller-Couch (who moved to Fowey as an adult), Margaret Roberts, and Violet Tweedale, as well as the young Agatha Christie (Johnston 293–322). As noted during the visit of the princess, Iredale kept a visitors’ book to record these and other notable customers—what a trove of autographs and information now unfortunately lost.

The art gallery, though primarily a place of business to sell artworks, also served as an exhibition space freely open to the public, as Iredale made plain in his advertisements. Besides the Woodville war painting exhibition in 1898, the gallery hosted exhibitions or paintings by the landscape painters Arthur Henry Enock and William Ayerst Ingram, the watercolorists Baragwanath King and Rose Wallis, the Scottish artist Sir Noel Paton, and the painter Herbert Schmalz. As The Torquay Times describes one exhibition, “Since the opening of Iredale’s Art Gallery on the Strand, no famous picture when on tour in the West leaves Torquay out of its itinerary, for it is sure there of a local habitation which will give it both name and fame” (“The Return from Calvary” 5). By 1898, Iredale established a connection with Messrs. T. Richardson and Co., in Piccadilly, London, to annually bring a collection of “the work of the most celebrated English masters” for exhibition and sale at his gallery, the visits of which became minor town events (“Pictures at Iredale’s Gallery” 8).

The library also served as a public meeting place—in fact, Iredale fully intended this function when moving to 13, the Strand, where he fitted out the first floor with several multi-purpose rooms. The library frequently hosted town government meetings from the 1890s onward. Other local business was often conducted in the library’s meeting rooms, such as the winding up of the Torquay Theatre Company in 1889 or a meeting of the Motor Bus Company in 1905 (“Winding up of the Torquay Theatre Company” 2; “Proposed New Electrical Station” 8). The newspaper also reports other charitable groups using the library for meetings, for example the Ipplepen Deanery Board of Religious Instruction in 1891 and the Kitson Testimonial Committee in 1893. The assembly room hosted numerous events, such as a series of twelve lectures on electricity and magnetism in 1892 (“Local News” 5). Most of these meetings appear to be intermittent and ad hoc. However, the longest lasting connection between the library and an organization is with the Torquay Chess Club, established in 1891. The club met several days per week in the smoking room of Iredale’s Library where “any visiting chess-player will be sure of a welcome and a good game,” as several chess-related periodicals attested (“Among Provincial Chess Clubs” 432). Initially, the club only allowed men members, but “the bye-law prohibiting ladies becoming members was rescinded” in 1902 (“Chess Notes” 2). In addition, the library hosted the club’s annual meetings every October as well as its matches with neighboring town clubs. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Torquay Chess Club freely called Iredale’s Library its “headquarters” (“Mr. J. H. Blackburne at Torquay” 3). It is unknown whether the Iredales themselves were members of the club, but the publisher Sir George Newnes, who owned a summer house in town, was said to be a member.

The library also served as a private business address for residents of the town. Several advertisements appearing throughout England use Iredale’s Library as the contact address—clearly, a function that Iredale allowed.[9] For example, in the London Standard of 1 January 1887, “A Lady, age 40, moving in good society, and accustomed to foreign travel, wishes to meet with another to share her well furnished house in Torquay; every home comfort; musical; elderly or invalid objected to; Church-woman; terms £2 2s weekly… Address A. R., Mr. Iredale’s Library, Torquay” (8). A sample of similar advertisements comes from a gentleman, “Oxford,” offering rooms and tennis (1888); “S. P.” looking to let a house in Newton Abbot (1890); a widow, “Meta,” desiring gentlewoman boarders (1895); and a gentleman, “S. M.,” soliciting paying guests (1897). Another group of advertisements offer to board and educate children: for instance, a young woman, “Syana,” looking to take charge of a girl (1891); an officer’s wife, “M. C.” and two boys (1892); and a widow, “Helen,” any child (1895). Most such advertisements, however, come from individuals looking for work: “Joan” looking for a position as a lady’s companion (1888); “Alpha” a housekeeper position (1889); “Aileen” a companion position (1892); a German woman “Linguist” a teaching position (1895); and an Oxford M.A., “E.,” a secretary’s post (1898). The oddest advertisement comes from the Devon and Exeter Gazette in August 1910: “Motor” offers to let his automobile with himself as chauffeur. Related to this use of the library as a mailing address, Iredale’s also served as a point of sale for concert, lecture, and performance tickets; a location for public display of plans or documents; and a site for receiving charitable contributions or subscriptions, as frequent newspaper advertisements often proclaimed.

V. The Material Culture of Reading

At this point, the experiment to re-construct the history and operation of a provincial circulating library might be deemed a modest success by some or “bland antiquarianism” by others. But Iredale’s Library, and circulating libraries in general, form a part of what could be called the material culture of reading—that is, all of the ways readers connect through, interact with, or relate to books as physical objects, not as the texts they contain. The field of Victorian studies often investigates the reactions or responses of readers to the contents of books, but the outward form of books and the non-reading use of books rarely elicit comment on their own. The only notable exception may be the study of Victorian periodicals, especially serialization practices. The fields of bibliography, book history, and library history have without a doubt long treated books as material objects, from authorship to printing to publishing to distribution, but such interest often ends when the book leaves the publisher’s, the bookseller’s, or the librarian’s door. There have been some exceptions: for example, Simon Eliot’s insightful article, “Never Mind the Value, What about the Price?” (2001), which examines all of the actual and hidden costs (e.g., candles) of reading during the Victorian period; or Leah Price’s wonderful book, How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain (2012), which examines all of the uses Victorians made of books other than reading. As Price puts it, the uses of printed matter may be reduced to three operations: “reading (doing something with the words), handling (doing something with the object), and circulating (doing something to, or with, other persons by means of the book)” (5). The latter operation corelates well with the idea of the material culture of reading and clearly describes the prime function of Iredale’s Library or any circulating library: the countless exchanges of books between librarians and customers, and the constant movements of books within and without this establishment and town.

But to focus only on the publication or circulation of books has the potential to overshadow the human beings doing the creating, exchanging, and moving of the books. Each interaction between humans involving the exchange of books creates a connection in a large social network of readers. Take Quiller-Couch’s “glee” in purchasing a used copy of The Bab Ballads from Iredale: maybe the purchase elicited some comment or conversation between the customer and the salesclerk about this book or potentially other books? Stables’s visits, as recounted, led to long conversations with Iredale in the shadow of the library’s impressive bookcases. Similarly, Princess Victoria’s tour of Iredale’s Library allowed the princess and the librarian to gossip about their common acquaintance. As the numerous activities at Iredale’s Library show, the library and its books (and to an equal extent the art) created countless opportunities for readers to connect with one another and became a place for creating and maintaining social connections between readers in the community.

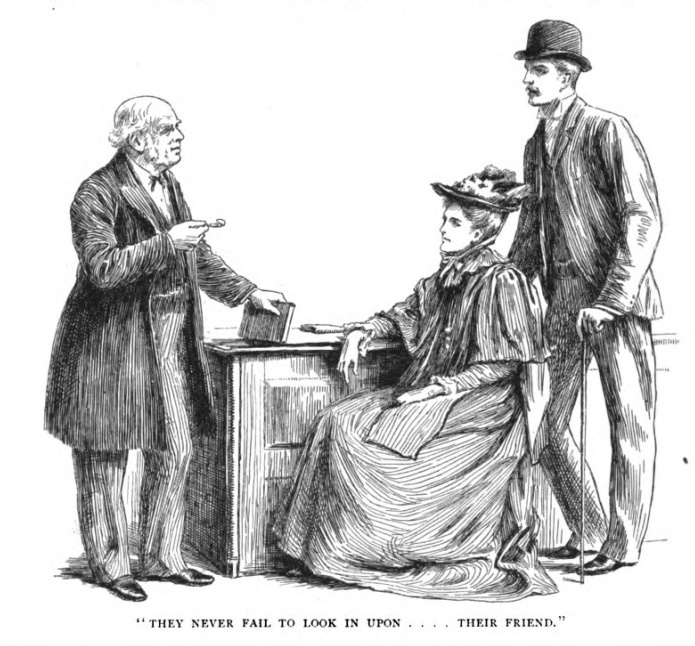

Illustration by Leslie Brooke from W. E. Norris’s _A Deplorable Affair_ serialized in _The English Illustrated Magazine_ (April 1892)

Yet, as busy and popular as Iredale’s Library proved to be, records of whatever reader interactions actually occurred in the library remain scarce. W. E. Norris’s novel A Deplorable Affair (1893), however, offers an imaginative account of the life of Iredale’s Library. The popular novelist Norris lived in Torquay and frequently visited the library, and he used the library and its owner as the inspiration for his short novel.[10] The narrator, Sykes, is a prosperous bookseller in Sandsea, a watering-place on the south coast, and he witnesses the budding romance between the cousins Beatrice Devereux, a poor relation who secretly writes novels, and Sidney Whitfield, an independent young gentleman, both relations of the wealthy spinster, Miss Whitfield. Sidney quickly falls in love with Beatrice, who mysteriously turns down his proposal though clearly in love herself. Meanwhile, the cad, Frederick Carleton, arrives in town and meets in secret with Beatrice, raising the concern of Sykes, which he relays to Sidney (the two have been friends since the latter was a boy). Miss Whitfield asks Beatrice to undertake an errand for her: to deliver a package of jewelry to a London dealer and return with their check. Sykes, coincidently on the same train, sees Beatrice embark with Carleton and witnesses her give the package to him on arrival in London. The jewelry is sold but the money disappears—Beatrice claiming it was stolen. Enraged, Miss Whitfield expels her niece from her home in spite of Sykes’s near certainty of Beatrice’s innocence. A year later the mystery clears: Carleton, in reality Beatrice’s ne’er-do-well brother, Edward, stole the money and fled to America, where he confessed his crime before dying. (Beatrice had remained silent in a misguided attempt to protect her brother.) Cleared of the crime and freed from her brother, Beatrice accepts Sidney’s proposal.

Illustration by Leslie Brooke from W. E. Norris’s _A Deplorable Affair_ serialized in _The English Illustrated Magazine_ (April 1892)

Local readers of A Deplorable Affair clearly saw Iredale and Torquay in the novel’s depiction of Sykes and Sandsea—in fact, The Torquay Times commented that the novel would be of interest to readers in the town and “may be said to reek of Torquay” (“Bachelors’ Elysium” 2). Sykes, in his public role as bookseller and librarian, occupies a prime vantage point for observing and meeting the townspeople. Sykes first meets Beatrice when she enters his shop one afternoon “carrying a pile of library volumes which she had been sent to exchange” by her aunt, and he and she “had a pleasant little talk together before she re-entered the heavy, old-fashioned barouche which was waiting for her at the door” (Norris 12). During their conversation, in praising a recent book, Sykes elicits Beatrice’s confession to being its author. Likewise, Carleton visits the shop to purchase a three-shilling novel and to enroll as a monthly subscriber, which gives Sykes the opportunity to conclude he is a “rascal” (38). Later in the novel, Sykes himself delivers books to Miss Whitfield at her home, “the particulars of the transaction which ensued for these [books] would interest nobody except bibliophiles,” but their gossip about Beatrice and Sidney proves more relevant to report (60–61). After the crime, Sykes hears ample gossip from his library customers:

And, dear me, how they did talk! During many successive days not a customer entered our shop but had his or her special theory about a scandal which had set all Sandsea agog; most of them, I suspect, only entered our shop for the purpose of enunciating their theories; and, although this was good for trade, it was painful for the tender-hearted trader. (156–57)

Nevertheless, Sykes confesses, he “listened to them [all] and told them nothing” (158).

Illustration by Leslie Brooke from W. E. Norris’s _A Deplorable Affair_ serialized in _The English Illustrated Magazine_ (May 1892)

The library itself becomes the scene of more meetings, since the shop utilizes “the suite of apartments on the first story as reading and conversation rooms” in their “more spacious premises on the Royal Parade,” though Sykes fears “certain malevolent people have accused me of keeping a place of public rendezvous, rather than a bookseller’s shop” (31). In fact, Beatrice and Carleton use the reading rooms frequently to meet, where Sykes catches them “seated close together in a dark corner, engaged in earnest conversation” (41). Later, he arranges for Sidney to meet Beatrice by relating that “Miss Devereux was not unfrequently to be met with in our reading-rooms between four and five o’clock in the afternoon” (97). During one of these visits, Sidney catches Beatrice and Carleton seated side by side in a “small, dimly-lighted apartment”; still later, Miss Whitfield catches Beatrice and Sidney “sitting hand in hand” in the same dim room (103, 109). Throughout the short novel, the buying, exchanging, and reading of books in Sykes’s shop becomes a pretext for chance conversations, clandestine meetings, and town gossip. In fact, Miss Whitfield sums it up best when she archly observes to Sykes, “I am so anxious to see those reading and conversation rooms of yours, you know. Which pays you best, do you think—the reading or the conversation?” (107–8). The final illustration of the novel’s serialization shows the lovers continuing to visit the library, with Sykes, book in hand, coming out from behind the counter.

Illustration by Leslie Brooke from W. E. Norris’s _A Deplorable Affair_ serialized in _The English Illustrated Magazine_ (July 1892)

Clearly, Norris’s novel, as fiction, cannot be considered an accurate historical record of what may have occurred in the reading rooms of Iredale’s Library. But, as evidenced by Princess Victoria’s visit and the other records discussed, such encounters through (or in spite of) books must have happened frequently in the rooms of the library. We tend to focus on libraries as places where books are stored or where books can be acquired or where books can be read, but they are also human institutions. Without a doubt, Iredale’s Library served as a nexus in Torquay’s social network that helped to create and maintain person-to-person connections across classes and genders. Books were just the medium.

Finally, how does the history of Iredale’s Library compare to other provincial circulating libraries? Certainly, Iredale’s Library, as described here, appears exceptional on many levels, as even contemporary observers frequently noted. But even a cursory investigation into a few other provincial Victorian circulating libraries reveals they too occupied a similar place at the center of the towns’ literary and social lives. For instance, in addition to lending books, Acock’s Library in Oxford sold books and offered printing and bookbinding; Lovejoy’s Library in Reading served as an address for residents’ correspondence and became a sales point for concert tickets; and Sutton’s Circulating Library in Fareham provided meeting space for groups, served as an address for residents’ correspondence, and became a sales point for various tickets and subscriptions. Of the hundreds of other Victorian circulating libraries, it is reasonable to assume that many, if not most, establishments occupied similar places at the center of their towns’ literary and social lives—with conversations over the bookman’s counter, gossip in the corners, and romance among the shelves.

published September 2019

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Bassett, Troy J. “‘More than a Bookseller’: Iredale’s Library as the Center of Provincial Literary Life.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Advertisement for Iredale’s Library. Torquay Pictorial, 1890, p. 49. Old Torquay. https://www.networktorbay.uk/old-torquay.html. 15 June 2018.

Advertisement for a Lady. Standard, 1 January 1887, p. 8. British Newspaper Archive. 15 March 2018.

Alston, Robin. Library History Database. Archived at http://digitalriffs.blogspot.com/2011/08/robin-alstons-library-history-database.html. (9 July 2019).

“Among Provincial Chess Clubs.” Womanhood (November 1902), p. 432. Hathitrust Digital Library. 9 June 2018.

“Bachelors’ Elysium.” Torquay Times, 25 October 1901, p. 2. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

“Chats with a Bookmaker.” Torquay Times, 17 February 1898, p. 8. British Newspaper Archive. 15 March 2018.

“Chess Notes.” Devon and Exeter Daily Gazette, 30 September 1902, p. 2. British Newspaper Archive. 27 March 2018.

Eliot, Simon. “Circulating Libraries in the Victorian Age and After.” The Cambridge History of Libraries in Britain and Ireland, edited by Alistair Black and Peter Hoare, vol. 3, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 125–46.

———. “Never Mind the Value, What about the Price? Or, How Much did Marmion Cost St. John Rivers?” Nineteenth-Century Literature, vol. 56, no. 2, 2001, pp. 160–197.

Gerring, Charles. Notes on Printers and Booksellers. Simpkin, Marshall, 1900.

Griest, Guinevere L. Mudie’s Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel. Indiana University Press, 1970.

“An Hour at Iredale’s Library.” Torquay Times, 1 December 1893, p. 8. British Newspaper Archive. 12 April 2018.

Johnston, J. Charteris. “Literary Torquay.” Devonshire Association, 1918, pp. 293–322. Hathitrust Digital Library. 22 April 2018.

“Local News.” Torquay Times, 2 September 1892, p. 5. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

“Mr. Iredale’s New Art Gallery.” Torquay Times, 11 April 1890, p. 6. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

“Mr. Iredale’s New Premises.” Torquay Times, 30 November 1888, p. 3. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

“Mr. Iredale’s Reading Rooms.” Torquay Times, 22 February 1889, p. 8. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

“Mr. J. H. Blackburne at Torquay.” Western Times, 29 November 1913, p. 3. British Newspaper Archive. 1 June 2018.

Norris, W. E. A Deplorable Affair. London: Methuen, 1893.

Pearson’s Gossipy Guide to South Devon. C. Arthur Pearson, 1902.

“Pictures at Iredale’s Gallery.” Torquay Times, 25 March 1898, p. 8. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

Price, Leah. How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain. Princeton University Press, 2012.

“Prince of Wales at Torquay.” Torquay Times, 2 September 1898, p. 8. British Newspaper Archive. 1 March 2018.

“Proposed New Electrical Station.” Torquay Times 3 February 1905, p. 8. British Newspaper Archive. 9 July 2019.

Quiller-Couch, Arthur. Memories and Opinions: An Unfinished Autobiography. Cambridge University Press, 1944.

“The Return from Calvary.” Torquay Times, 15 July 1892, p. 5. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

Roberts, William. “They Yelled as Torquay’s First Car Broke Down.” Torquay Times, 20 October 1950, p. 4. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

“A Souvenir of the Royal Visit to Torquay.” Devon and Exeter Daily Gazette, 10 November 1886, p. 4. British Library Newspapers. 13 June 2018.

Wilson, Charles. First with the News: The History of W. H. Smith 1792–1971. Capes, 1985.

“Winding up of the Torquay Theatre Company.” Devon and Exeter Daily Gazette, 26 March 1889, p. 2. British Library Newspapers. 13 June 2018.

Yates, Edmund. “Cheating the Winter at Torquay.” Torquay Times, 30 January 1891, p. 7. British Newspaper Archive. 15 June 2018.

ENDNOTES

[1] The details that follow come from “Prince of Wales at Torquay,” Torquay Times (25 March 1898), p. 8

[2] Notably, after the 1886 visit, the town had chosen Iredale as its representative to present the town’s gift to the Duchess of Sutherland as recounted in “A Souvenir of the Royal Visit to Torquay,” Devon and Exeter Daily Gazette (10 November 1886), p. 4.

[3] As of this writing, Alston’s database does not have a fixed location. Andrew Prescott has a copy on his blog, http://digitalriffs.blogspot.com/2011/08/robin-alstons-library-history-database.html.

[4] The history of these two circulating libraries can be found in Guinevere L. Griest’s Mudie’s Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel (1970) and Charles Wilson’s First with the News: The History of W. H. Smith 1792–1972 (1985) respectively.

[5] This, admittedly eclectic, sample of libraries comes from an examination of existing library labels on a few dozen Victorian novels from the author’s personal collection. Alston’s list noted above is more definitive for the period before 1850.

[6] Simon Eliot’s chapter “Circulating Libraries in the Victorian Age and After” (2006) is a notable exception.

[7] The details that follow come from Charles Gerring, Notes on Printers and Booksellers (Simpkin, Marshall, 1900), pp. 80–81.

[8] The details of the building that follow come from “Mr. Iredale’s New Premises” Torquay Times (30 November 1888), p. 3.

[9] The advertisements appeared in The Morning Post, The Standard, and The Western Daily Press.

[10] Norris’s novel was first serialized monthly in The English Illustrated Magazine from April to July 1892 with illustrations by Leslie Brook. Methuen published the novel in one volume shortly after the serialization with a selection of the serial illustrations.