Abstract

The ‘Blue Plaque’ scheme, which places memorial tablets on houses in London once occupied by distinguished people, was inaugurated in 1868, when the Royal Society of Arts placed the first plaque on the house in Holles Street (off Oxford Street) where Lord Byron was born. This was the first of many plaques: at least 33 were in place by the end of the century, with more planned. The distinctive blue circular design was adopted in 1901 and the scheme continues to operate today under the management of English Heritage. This essay argues that the scheme drew on key Romantic ideas about commemorative practice, expressed by William Godwin, William Wordsworth and Samuel Rogers, as well as memorialising Romantic authors. It suggests that the “Blue Plaques” should be read in the context of a number of pantheonic initiatives undertaken during the period of the Reform agitation, which aimed to promote cultural consensus in the present, by creating consensus about the noteworthy individuals of the past.

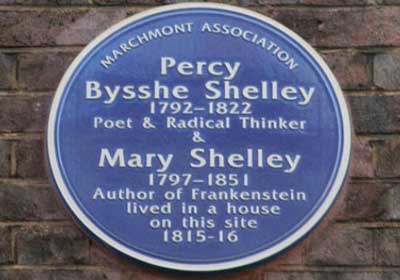

Figure 1: A plaque commemorating the Shelleys, Marchmont Street, London, installed by the Marchmont association as part of one of the many commemorative schemes that imitate the official ‘blue plaque’ scheme administered by English Heritage

This scheme should be understood as one of many efforts throughout the nineteenth century to construct a national, secular pantheon of notable individuals from the past. Such efforts gained new significance from the long debate about how to reform Parliament by redrawing constituency boundaries and extending the franchise. This debate extended from the agitation that preceded the Reform Bill of 1832, through the Second Reform Bill of 1867, to the repercussions that followed that of 1885 and into the agitation for women’s suffrage at the beginning of the twentieth century. Private pantheons, such as ![]() the Temple of British Worthies at Stowe, completed in 1735, constructed lists of the great, but did not necessarily represent public consensus (Robinson). From the 1790s on, however, “plans for national pantheonic structures were rife” (Yarrington 107). Pantheons could be discursive, like Hazlitt’s Spirit of the Age (1825), sculptural, like those in

the Temple of British Worthies at Stowe, completed in 1735, constructed lists of the great, but did not necessarily represent public consensus (Robinson). From the 1790s on, however, “plans for national pantheonic structures were rife” (Yarrington 107). Pantheons could be discursive, like Hazlitt’s Spirit of the Age (1825), sculptural, like those in ![]() Westminster Abbey and

Westminster Abbey and ![]() St Paul’s Cathedral, or popular, like the waxworks in

St Paul’s Cathedral, or popular, like the waxworks in ![]() Madame Tussaud’s collection and the busts that decorated the “pantheon” assembly rooms in

Madame Tussaud’s collection and the busts that decorated the “pantheon” assembly rooms in ![]() Oxford Street (1772-1814). But wherever they appeared, pantheonic lists of the individuals who counted from the past helped produce a consensus about the nation’s shared heritage, during a period of intense uncertainty about who would be counted–literally counted at the ballot box and metaphorically counted as members of the nation–in the present.

Oxford Street (1772-1814). But wherever they appeared, pantheonic lists of the individuals who counted from the past helped produce a consensus about the nation’s shared heritage, during a period of intense uncertainty about who would be counted–literally counted at the ballot box and metaphorically counted as members of the nation–in the present.

The scheme’s earliest supporters were closely associated with the cause of Reform. Ewart was “a Liberal with radical leanings” who advocated widening the reforms of 1832 and supported national education (Farrell). When his own commemorative plaque was installed in 1963 it described him simply as “Reformer” (E. Cole 10). The scheme’s “convenor” at the Society of Arts was George C. T. Bartley, a civil servant and later Member of Parliament who established the National Penny Bank in 1875 to promote thrift among the poor (Owen). The first tablet the Society installed was on Byron’s birthplace in ![]() Holles Street, in 1868.[1] The society published annual lists of the memorials it had installed; there were 33 of them by the end of the century, with many more planned (“Memorial Tablets” 827).

Holles Street, in 1868.[1] The society published annual lists of the memorials it had installed; there were 33 of them by the end of the century, with many more planned (“Memorial Tablets” 827).

These memorial tablets were part of a reconfiguration of urban space brought about by a variety of factors. London’s population exploded, rising from about one million in 1801 to over seven million by 1911, leaving the metropolis feeling both teeming and sprawling.[2] New civil engineering projects were undertaken, such as the ![]() Chelsea,

Chelsea, ![]() Victoria and

Victoria and ![]() Albert embankments (1874), and new landmarks constructed, such as the Crystal Palace (1851, relocated 1854), the rebuilt Houses of Parliament (1840-1870) and the Albert Hall (1871). More extensive transport links were required, including roads and railways, several bridges across the

Albert embankments (1874), and new landmarks constructed, such as the Crystal Palace (1851, relocated 1854), the rebuilt Houses of Parliament (1840-1870) and the Albert Hall (1871). More extensive transport links were required, including roads and railways, several bridges across the ![]() Thames, and the London Underground Railway (from 1863). Gaslight and smog changed the experience of the city streets, while music halls and the

Thames, and the London Underground Railway (from 1863). Gaslight and smog changed the experience of the city streets, while music halls and the ![]() London Zoo (opened to the public in 1847) offered new ways to pass leisure time. These developments were accompanied by an imaginative remapping of the city undertaken by writers and artists such as Thomas De Quincey, Pierce Egan, Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold, Henry Mayhew and Charles Dickens.

London Zoo (opened to the public in 1847) offered new ways to pass leisure time. These developments were accompanied by an imaginative remapping of the city undertaken by writers and artists such as Thomas De Quincey, Pierce Egan, Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold, Henry Mayhew and Charles Dickens.

The physical renovation of London and its imaginative recreation came together in an extraordinary range of plans for new public memorials to distinguished individuals. What Stephen Behrendt has called an “explosion of public monumental sculpture” at the beginning of the nineteenth century remade the city’s public spaces as quasi-national galleries of civic memorials (72). As part of the “statuemania” that seized several European capitals in the nineteenth century, many public memorial sculptures were erected in London, including Nelson’s column (1839-43), the ![]() Albert Memorial (1872-76), and

Albert Memorial (1872-76), and ![]() Eros in

Eros in ![]() Piccadilly Circus (1893), which commemorates the Earl of Shaftesbury.[3] As a result, London developed significant clusters of commemorative sculpture, formed into pantheons which were not enshrined in a single structure, but distributed across newly developed geographies of urban space (Read 67). The Blue Plaque scheme contributed to this drive to memorialise the past and extended it to urban spaces that were unsuitable for statues. At the same time, it resisted the waves of demolition that often accompanied urban renovation projects, by insisting that plaques could only be erected where the original building was still standing.

Piccadilly Circus (1893), which commemorates the Earl of Shaftesbury.[3] As a result, London developed significant clusters of commemorative sculpture, formed into pantheons which were not enshrined in a single structure, but distributed across newly developed geographies of urban space (Read 67). The Blue Plaque scheme contributed to this drive to memorialise the past and extended it to urban spaces that were unsuitable for statues. At the same time, it resisted the waves of demolition that often accompanied urban renovation projects, by insisting that plaques could only be erected where the original building was still standing.

The coordination and ambition that the Society of Arts brought to the scheme was unprecedented, but the conception was Romantic through and through, from the understanding of commemoration it endorsed, to the experience of the city it promoted, to the individuals it memorialised. William Godwin’s Essay on Sepulchres (1809) was an early and prescient example of the rising interest in constructing a national pantheon. Rejecting “sumptuousness of decoration” in funerary monuments, Godwin proposed to erect simple markers over the graves of notable individuals throughout the country (Godwin 18). Contemporary commentators found it difficult to reconcile this plan with Godwin’s politics: the Monthly Review pointedly remarked that the proposal was “more in the style of antient piety than of modern philosophy” (qtd. in Godwin 3). “[M]odern philosophy” is a code-word here for radicalism, but although Godwin’s proposal was not avowedly radical, it was nonetheless part of his Reformist agenda. He insisted that honouring the past was not “hostile to that tone of spirit which should aspire to the boldest improvements in future.” Instead, he asserted that “The genuine heroes of the times that have been, were the reformers,” and, so, commemorating them would inspire emulation (Godwin 6). Godwin’s concluding claim that maps showing the location of the monuments would be more valuable than “the ‘Catalogue of Gentlemen’s Seats,’ which is now appended to the ‘Book of Post-Roads through Every Part of Great Britain’” reveals his Reformist agenda (30). His scheme would help to redraw the imaginative map of Britain; no longer navigating by aristocratic landmarks, the citizens of the Reformed nation would locate themselves in relation to the great individuals of the past, whatever their class or party.

Godwin’s pantheon would not transform the national landscape so much as reform the national consciousness. Drawing on contemporary associationist psychology, he explained that his object was “to mark the place where the great and excellent of the earth repose, and to leave the rest to the mind of the spectator” (18).[4] The resulting pantheon would exist as much in the consciousness of the informed individual as in the physical environment. Godwin didn’t hope to incite dissent by celebrating historical radicals, but to foster consensus. He wanted the list of those commemorated to be “made on the most liberal scale,” claiming that his project offered “scanty room for party and cabal” (27). The new national pantheon needed to be sufficiently “liberal” to transcend party and class allegiance, and embody a new consensus about the nation’s identity. Godwin acknowledged that the simple wooden cross he prescribed for marking graves might be impractical in the crowded city. In this case, he asserted, “A horizontal stone on the level of the pavement, or a mural tablet, where the grave is enclosed within a building, is abundantly enough” (25).

Samuel Rogers, in the “Genoa” section of his poem Italy (1822-28), visited the house of Andrea Doria –the admiral who re-established the Republic of ![]() Genoa in the sixteenth century– and took special note of the memorial plaque on its outside wall:

Genoa in the sixteenth century– and took special note of the memorial plaque on its outside wall:

He left it for a better; and ’tis now

A house of trade, the meanest merchandise

Cumbering its floors. Yet, fallen as it is,

’Tis still the noblest dwelling – even in Genoa!

And hadst thou, Andrea, lived there to the last,

Thou hadst done well; for there is that without,

That in the wall, which monarchs could not give,

Nor thou take with thee, that which says aloud,

It was thy Country’s gift to her Deliverer. (Rogers 44)

The custom of marking houses in this way, Rogers added in a note to this passage, was “well worthy of notice”; remarking how “rare are such memorials among us,” he asserted that they were “evidences of refinement and sensibility in the people” (54). Rogers’ note (but not his poem) was quoted in the Journal of the Society of Arts when the idea of setting up memorial tablets was being mooted (“Memorials of Eminent Men” 437).

The text that shaped the Society’s understanding of the city most, even if it went unmentioned, was Wordsworth’s The Prelude. Among the wonders he looked forward to seeing in London in the 1805 version, Wordsworth included “Statues, with flowery gardens in vast Squares” (1805: 7.134). By 1850, when the secular pantheon was much more extensive, he made clear that these statues were elements of a well-ordered and maintained pantheon of mostly military heroes: “Statues– man,/ And the horse under him–in gilded pomp/ Adorning flowery gardens, ’mid vast squares” (1850: 7.133-35). When he arrived, however, he found a pantheon not among statues (which are not mentioned again) but among shop signs showing “physiognomies of real men,/ Land-warriors, kings, or admirals of the sea,/ Boyle, Shakespeare, Newton, or the attractive head/ Of some quack-doctor, famous in his day” (1850: 7.164-67). These commercial signs were accompanied by a cacophony of written messages, “blazon’d Names. . . [on] fronts of houses, like a title page/ with letters huge inscribed” (1850: 7.158-61). Wordsworth’s simile here probably fuses two observations: firstly, booksellers’ practice of pasting up title pages on boards outside their shops to serve as advertisements, and secondly, tradesmen’s practice of using a famous author’s name or likeness as a shop sign, especially if the site of the shop was associated with him or her (Raven 170). The piratical publisher William Benbow used Byron’s head as his shop sign in the 1820s and a correspondent of the Society of Arts noted in 1866 that a pub in ![]() Fetter Lane bore the sign “Here lived Dryden, the poet” (A.S. Cole 588). One source of the complex anxiety that London generated for Wordsworth in The Prelude, then, was the realisation that the city did not have a stable, prestigious pantheon of great men commemorated in statues, as he had imagined, but a shifting, commercialised and debased pseudo-pantheon of advertisements and shop signs, in which Boyle, Shakespeare or Newton were pressed into the service of tradesmen and forced to mingle with quack doctors.

Fetter Lane bore the sign “Here lived Dryden, the poet” (A.S. Cole 588). One source of the complex anxiety that London generated for Wordsworth in The Prelude, then, was the realisation that the city did not have a stable, prestigious pantheon of great men commemorated in statues, as he had imagined, but a shifting, commercialised and debased pseudo-pantheon of advertisements and shop signs, in which Boyle, Shakespeare or Newton were pressed into the service of tradesmen and forced to mingle with quack doctors.

The Society of Arts’ plan to mark the houses of eminent men in London aimed to provide the benefits that Rogers praised, while counteracting the disappointment Wordsworth felt. Having noted that some foreign cities displayed signs at the houses of notable individuals which “few would notice. . . if to do so required hunting in a ‘Murray’s Guide,’” Bartley imagined an annotated city, whose buildings would be written over with its own tourist handbook (“Memorials of Eminent Men” 437).[5] The Blue Plaque scheme thus participated in the general rise of interest in literary tourism and the homes of authors exemplified by William Howitt’s Homes and Haunts of the Most Eminent British Poets (1847) and studied by Nicola Watson. Unlike Wordsworth’s cacophonous experience of the city, in which every building seemed to be shouting at once, Bartley imagined a decorous register of past achievements. The Times remarked that “[n]othing could be more fertile in interest than to make our houses their own biographers” (“Memorial Tablets in London” 5). The intended readers of the plaques, however, were not primarily tourists but residents of the city, especially the lower classes who were the focus of Ewart and Bartley’s philanthropic and political work. “To travellers up and down in omnibuses, &c”, Bartley wrote, the plaques would provide “an agreeable and instructive mode of beguiling a somewhat dull and not very rapid progress through the streets” (“Memorials of Eminent Men” 437).

In order not to be confused with the pseudo-pantheon Wordsworth discovered in London’s shop signs, this scheme carefully distanced itself from the taint of commerce. Bartley cautioned that “any attempt which might be made in this advertising age to utilize the memory of a former inhabitant for commercial advantages. . . should be as much as possible avoided” (“Memorials of Eminent Men” 437). For the lower-class man on the omnibus, only recently admitted to full political membership of the nation, the city was imagined by the scheme’s supporters as a space of monotony and alienating drudgery, choked with traffic and studded with advertisements. The blue plaque scheme offered an alternative experience of the city, in which its monotony was relieved by instructive diversions, its commercialism was accompanied by civic pride, and its alienating character was overcome by a sense of shared inheritance. Everyday reminders of past greatness could make the modern city navigable, intelligible, and edifying. The plaques offered to construct a pantheon that would not be gathered in one structure but distributed across the whole city. It would be equally accessible to all its inhabitants, and would invite them to imagine themselves as part of the same nation as each other and as the celebrated city-dwellers of the past.

published December 2012

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Mole, Tom. “Romantic Memorials in the Victorian City: The Inauguration of the ‘Blue Plaque’ Scheme, 1868.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Baker, Margaret. Discovering London Statues and Monuments. 5th ed. Princes Riseborough, UK: Shire Publications, 2002. Print.

Bayley, Stephen. The Albert Memorial: The Monument in its Social and Architectural Context. London: Scolar Press, 1981. Print.

Behrendt, Stephen C. “The Visual Arts and Music.” Romanticism: An Oxford Guide. Ed. Nicholas Roe. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. 62-76. Print.

Bremner, G. Alex. “The ‘Great Obelisk’ and Other Schemes: The Origins and Limits of Nationalist Sentiment in the Making of the Albert Memorial.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 31.3 (2009): 225-249. Print.

Brooks, Chris, ed. The Albert Memorial. The Prince Consort National Memorial: its History, Contexts, and Conservation. London and New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2000. Print.

“Byron Memorial in Holles-Street.” Journal of the Society of Arts. 48 (1900): 620. Print.

Carpenter, Humphrey. The Seven Lives of John Murray. London: John Murray, 2008. Print.

Cole, A.S. “Memorial Tablets.” Letter. Journal of the Society of Arts 14 (1866): 588. Print.

Cole, Emily, ed. Lived in London: Blue Plaques and the Stories Behind Them. London and New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2009. Print.

‘Epsilon.’ “Memorial Tablets.” Letter. Journal of the Society of Arts 12 (1864): 362. Print.

Farrell, S. M. “Ewart, William (1798–1869).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Web. 3 September 2009. <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9011>.

Getsy, David J. Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877-1905. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2004. Print.

Godwin, William. “Essay on Sepulchres.” Political and Philosophical Writings of William Godwin. Ed. Mark Philp. Vol. 6. London: Pickering and Chatto Ltd., 1993. Print.

Grytzell, Karl Gustav. County of London: Population Changes 1801-1901. Lund, Sweden: The Royal University of Lund, 1969. Print.

Hansard, Thomas Curson. “Residences of Deceased Celebrities.” Parliamentary Debates. London: Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, 1863. Print.

Howitt, William. Homes and Haunts of the Most Eminent British Poets. 2 vols. London: 1847. Print.

Journal of the Society of Arts 12 (1864): 364. Print.

“Memorials of Eminent Men.” Journal of the Society of Arts 14 (1866): 437-439. Print.

“Memorial Tablets.” Journal of the Society of Arts 48 (1900): 827. Print.

“Memorial Tablets in London.” The Times 4 September 1873: 5. Print.

Michalski, Sergiusz. Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage, 1870-1997. London: Reaktion, 1998. Print.

Owen, W. B. “Bartley, Sir George Christopher Trout (1842-1910).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Rev. Anita McConnell. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Web. 17 August 2009. < http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/30629>.

Plaque Guide. http://www.plaqueguide.com/. Uses geospatial data to mark plaques on an interactive map. Web. 25 October 2012.

Phillips, Mark Salber. Society and Sentiment: Genres of Historical Writing in Britain, 1740-1820. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2000. Print.

Raven, James. The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade, 1450-1850. London and New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2007. Print.

Read, Benedict. Victorian Sculpture. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1982. Print.

Robinson, John Martin. Temples of Delight. London: National Trust, 1994. Print.

Rogers, Samuel. “Genoa.” Italy: A Poem. London: Edward Moxon, 1840. 44-45. Print.

Walsh, John. “Heritage: Byron in the Bathware Section,” The Independent (London). Web. 4 October 2012. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/heritage-byron-in-the-bathware-section-8196494.html.

Ward-Jackson, Philip. Public Sculpture of the City of London. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 2003. Print.

Watson, Nicola J. The Literary Tourist: Readers and Places in Romantic and Victorian Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2006. Print.

Yarrington, Alison. “Popular and Imaginary Pantheons in Early Nineteenth-Century England.” Pantheons: Transformations of a Monumental Idea. Eds. Richard Wrigley and Matthew Craske. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2004. 107-21. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] Byron’s birthplace was demolished in 1889, and the site became part of John Lewis Department Store, which erected a new memorial to Byron, in the form of a bronze relief bust, in 1900 (“Byron Memorial in Holles-Street” 620) and a plaque inside the store in 2012 (Walsh).

[2] The 1801 Census recorded London’s population as 1,114,644; the 1911 census recorded it as 7,251,358 (Grytzell 120).

[3] For a comparative account of Parisian statuemania, see Michalski, 13-55. The history of the Albert Memorial is examined in detail in Brooks, Bayley and Bremner. Alfred Gilbert’s Eros (Memorial to Antony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury) is discussed in Getsy, 87-117 passim. Useful reference works on London’s statuary include Ward-Jackson and Baker.

[4] On the connection between Godwin’s Essay and associationist psychology, see Phillips, 324-27.

[5]> On the publishing success of Murray’s tourist guidebooks, see Carpenter, 165-76.