Abstract

J. T. Grein’s founding of the Independent Theatre Society in 1891 marks a turning point in the cultural history of British theater. For the first time, the London stage had a theater that eschewed popular and profitable forms and embraced avant-gardism. While the Independent Theatre provided an alternative to the commercial theater, drama critics began to define their work as a non-commercial assessment of theater. Focusing on 1893, Miller demonstrates that reviewers in the early 1890s either directly used the Independent Theatre to define their own cultural roles or indirectly reflected the Independent Theatre’s concept of writing for an audience that is elevated above mass culture.

J. T. Grein established the Independent Theatre Society in 1891, providing London with a non-commercial, subscription-based theater that was the equivalent of ![]() Paris’s Théâtre Libre or

Paris’s Théâtre Libre or ![]() Berlin’s Freie Bühne. For decades, Victorian writers had decried the theater for catering to the masses, and such criticism led, in the late-nineteenth century, to a persistent call for a non-commercial theater.[1] The prominent theater critic William Archer praised Grein’s society specifically because he deplored the state of London theater:

Berlin’s Freie Bühne. For decades, Victorian writers had decried the theater for catering to the masses, and such criticism led, in the late-nineteenth century, to a persistent call for a non-commercial theater.[1] The prominent theater critic William Archer praised Grein’s society specifically because he deplored the state of London theater:

If such an institution was needed in Paris, how much more in London! Here we have not a single theatre that is even nominally exempt from the dictation of the crowd. Here the actor-manager reigns supreme. Here the upholsterer runs rampant, and it takes a hundred performances to pay his bill. Here the Censor swoops down on unconventional ethics, while he turns his blind eye to conventional ribaldry. Here the average intelligence of “the drama’s patrons” is much lower than in

France, and there are far fewer loop-holes of escape from its dominion. (“The Free Stage and the New Drama” 666)

Another proponent of a non-commercial venue was the novelist George Moore who called for a national “subventioned theater” that would “allow us to say what we have to say, and in the form which is natural and peculiar to us” (“Théâtre Libre” 227-29).[2] Grein himself, in an interview in the Chronicle, defined his society’s “mission” as “not so much to bring out new actors as to produce plays which have a literary and artistic merit, but no commercial value, so that they do not appeal to the ordinary theatre manager.”

The Independent Theatre Society marks a turning point in the cultural history of British theater. For the first time, the London stage had a theater that eschewed popular and profitable forms (which were, by extension, conservative) and embraced avant-gardism. Forward-thinking theater criticism such as that of Archer and Moore had prepared the way for the Independent Theatre, and in the early 1890s, theater criticism developed a strong emphasis on elevating not only the theater but also the drama critic above mass culture. This movement away from a theater that was dominated by commercial interests and public tastes would change not only the plays that were produced, but also the place of theater in society.

A. B. Walkley’s theater column, “Some Plays of the Day,” in the Fortnightly Review on April 1, 1893, demonstrates, through its omnibus title and its survey of various different plays, that the views of critics were shaped by the context in which they viewed a play—not only by the events of the day, but also by the other plays that they had recently seen. Moreover, in his introduction, Walkley suggests that a play’s “failure may be vastly more important than a success, and some luckless opuscule, which has been hissed off the stage, more significant, because marking a new departure, than some triumphant masterpiece which presents no essential variation of type” (468). This observation suggests not only that one must consider a play within its moment in theater history, but also that the failures of some plays were directly related to the successes of others as productions vied with each other for market share. Walkley offers his assessment of plays as an avant-garde alternative to the commercial marketplace: he can discern the importance of plays even if they do not enjoy popular success. Walkley thus reflects the division between the commercial and experimental theater that marked the early 1890s on the London stage, and his position is representative of a cluster of related phenomena in theater criticism in 1893—phenomena that marked a departure from earlier writing about the theater. These phenomena include the critic distancing himself from the theater audience, although not always for avant-garde purposes, and calling for an elevation of the stage in various ways.

These critical trends, emerging close in time to the establishment of the Independent Theatre, rightly belong to the 1890s generally and cannot be isolated strictly within a particular year. Nevertheless, I believe that 1893 is a watershed year for this shift in theater criticism. The success with which theater reviewers were defining themselves as professionals distinct from the theater-going public, and the importance of the year 1893 in this development, is evident in the fact that 1893 saw the publication of at least two collections of a theater critic’s reviews: Joseph Knight’s collection of earlier reviews from the Athenaeum, and the first annual volume of William Archer’s collected essays, The Theatrical World, a series which would continue through 1897. (Walkley’s Playhouse Impressions had appeared in 1892.) Paradoxically, distinguishing themselves from commercial measures of a play’s success provided critics with the professional platform from which to reap commercial rewards as they marketed their collected essays in book form.

In varying degrees, drama columnists of 1893 echoed Walkley in defining their reviews as a critical, rather than commercial, arena for plays. Notably, two very different publications, the Athenaeum and the Westminster Review, both defined their theater criticism as a non-commercial measure of a play’s success. Joseph Knight, in the Athenaeum, regularly distinguished his opinion from the way in which the audience received the play.[3] There is evidence of such a distinction between reviewer and audience in reviews of other genres at this time, as well. Reviews of novels and poems, however, do not rise to such a pitch of dismay over an audience’s judgment as does the Athenaeum’s pronouncement that an awful performance was well received by its viewers:

“Uncle Silas,” an adaptation by Mr. Seymour Hicks and Mr. Laurence Irving of the novel of Mr. Sheridan Le Fanu, obtained a favourable reception at the Shaftesbury on Monday afternoon. . . . Mr. Haviland acted with much melodramatic power as Silas, and Miss Irene Vanbrugh was agreeable in a small part. Besides being too long, however, the play lacks sympathy, and is terribly repellent. It is long since the public has been treated to such a banquet of horrors. (1893:1, 228)

On 28 January 1893, an Athenaeum review of W. Lestocq’s “The Sportsman,” an adaptation of Georges Feydeau’s “Monsieur Chasse,” took a nationalist position, attributing the play’s weakness to its Frenchness, but noted that the audience found it humorous: “Its situations are inconceivable in England, matters are brought forward and come to nothing, characters are introduced in a fashion equally purposeless and silly, and the whole, though the wit and the wickedness are together rooted up, remains obviously and flagrantly French. None the less it furnishes opportunities to actors, and on presentation extorts much laughter” (131). While “wit and wickedness,” specifically sexual forwardness, were qualities that Victorian critics associated with the French, so were formulaic and predictable plots, which is Knight’s objection here. Mentioned after the reviewer’s negative evaluation of the play, the enthusiasm with which the audience greets the production suggests that the spectators lack the discrimination of the critic. The reviewer in this case is not avant-garde; rather, his nationalism serves a conservative moral stance when he responds to a scene similar to one that appears in Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan: “When, again, the heroine is hidden in the bedroom of the man with whom she has taken refuge—when he takes off his coat and waistcoat, as if for the purpose of compromising her, and with dress thus ‘disarranged’ is visited by a police official, who duly enters particulars in a note-book—we feel that we are in Paris, not London” (132).

In contrast to the Athenaeum‘s relative conservatism, the Westminster Review in 1893 espoused an avant-garde stance, specifically by embracing the sexual forwardness of French writing that the Atheneaum had derided. It provided an ironic view of the conservatism of the London stage as it, too, enacted a division between critics and audiences in its review of Charles Hallam Elton Brookfield’s To-day, an adaptation of M. Victorien Sardou’s Divorçons, at the Comedy Theatre:

In spite of the excisions of the innuendos with which the original abounds, and which would be ill-suited to such a haven of virtue as our capital; notwithstanding all the liberties which have been taken in order to disfigure M. Sardou’s masterpiece beyond recognition, to the intense indignation of that eminent playwright, there is left in To-day more than enough wit and satire to suffice for one evening’s delectation for a large class of playgoers. (104)

The attitude here is one of lightly veiled contempt for the theater audience, both for its moral stodginess and for its unworldly lack of awareness of what it is missing in the continental theater. Similarly, the reviewer notes that “The progress of French music is great indeed at the present time, and is not being followed very closely in this country” (108).

In both the Westminster Review and the Athenaeum, the critic distances himself from the play’s commercial success and redefines the relationship between reviewer and audience. The reviewer is no longer representative of the theater audience. Rather, he judges not only the production, but also the taste of the audience. When Knight, in an April 8 review of The Black Domino, identified the audience’s continued enthusiasm for melodrama, he faulted the playgoers more than the playwrights. First, Knight judges the play within the specific context of the genre of melodrama, noting its popularity despite its lack of originality:

Melodrama becomes a more and more hopelessly conventional entertainment. It might almost be rolled off the reel and cut into lengths like tape. Neither better nor worse than a hundred previous pieces is “The Black Domino” of Messrs. Sims and Buchanan. It has, indeed, pretty and suggestive surroundings and it hits public taste, and is, consequently, a success. It is, on the other hand, evolved out of nothing, is a rifacimento of well-known situations; it has no characters that are not commonplace stage types; it proves nothing, and leads nowhere. (451)

Then, Knight effectively excuses the playwrights for having to write for such an undiscriminating crowd:

We are not scolding Messrs. Sims and Buchanan for writing down to that level of their patrons. They have aimed at higher work, and found no satisfactory market for their wares. Like most producers of melodrama, they have learnt that jerry buildings are practically better than more substantial structures. . . . In these things and in some scenes of hackneyed humour the audience finds unending delight. A certain form of entertainment awaits, moreover, the critic who recognizes the sources of situation or character, and spends his time metaphorically, like a French critic, in saluting his old acquaintance. (451-52)

Once again, the pleasures of the critic are distinct from the pleasures of the audience. While the familiar conventions of melodrama “carr[y] away the public,” the critic intellectually recognizes the history and references within those conventions (451). Knight thus underscores the critic’s possession of a particular intellectual faculty and a body of specialized knowledge. His comment on French critics refers to the English critics’ view of French drama as formally conventional even as it was socially and sexually forward-thinking for English audiences.

Such a distinction between drama critic and theatrical audience emerged in force only at the end of the century. Prior to the 1890s, drama critics invoked a greater sense of identification with playgoers, rather than a distance from them. On 13 January 1883, Knight draws a distinction among different types of playgoers, but not between them and the critic: “Miss Genevieve Ward’s reappearance in ‘Forget-me-Not’ adds one more to the entertainments in London which can be seen by the intellectual playgoer with pleasure and advantage” (61). Here, the critic is one of the intellectual class to which he refers. In fact, on 11 January 1873, an Athenaeum review of W. S. Gilbert’s The Wicked World notes that, “Close attention and some intelligence on the part of the audience are necessary to the enjoyment of the whole,” without suggesting that the audience is less capable than the critic of supplying such attention and intelligence (58). Additionally, the review includes a rhetorical gesture that serves to reach out to its readers: “Few readers of intelligence will fail, however, to be thankful for such a work, or would be otherwise than glad that pieces of this description should be frequently given at one, at least, of our theatres” (58). On 25 January 1873, Knight employs a unifying sense of national identity, referring to himself as “an average Englishman . . . contemplating the kind of morality engendered among Parisian writers,” in this case M. Alexandre Dumas, fils’s, La Femme Claude, produced in Paris (124). Although a 26 April 1873 review notes “the applause of ignorant crowds” for Henry Irving’s over-acting in The Fate of Eugene Aram, it limits such poor audience judgment to the assessment of acting, concluding, “The reception of the play was triumphant. In spite of the almost sepulchral character of the interest and in spite of, or, perhaps, by reason of the faults of the acting, it will probably enjoy an extended popularity” (544). In fact, in a review of Henry J. Byron’s “Fine Feathers,” the following week, Knight ascribes a faculty of self-awareness to the audience, a self-awareness that once again leads to rejection of French drama:

Want of probability is ordinarily a less serious drawback from a play than want of movement. There are few extravagances which an audience will not overlook when once its interest and attention are excited. Herein lies the secret of the success of the older Dumas. . . . So rapid, however, is the evolution of plot, and so constant the succession of incident, that the spectator has not time to investigate the truth or vraisemblance of what is put before him. When subsequently he turns over in his mind the nature of the entertainment by which he has been pleased, his feelings seldom extend beyond a whimsical discontent at his capacity to extract amusement from what, to his judgment, is wholly preposterous. (576)

Although the audience is easily swayed by action, this impressionability is distinct from its intellectual assessment of drama. In contrast, in the 1890s critics reserved this intellectual faculty of evaluation for themselves, suggesting that they were capable of appreciating the finer points of drama in a way that the typical playgoer could not.

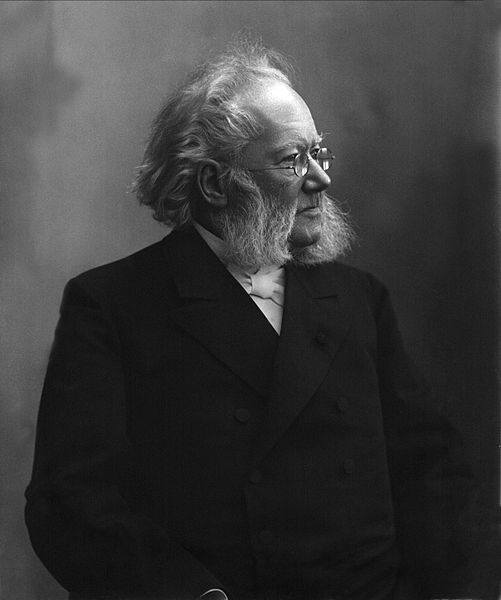

The Independent Theatre played an important and explicit role in the way in which the Westminster Review distinguished itself from theater audiences in 1893. The Westminster Review began its theater column a few months after the Independent Theatre opened in 1891, and by 1893, when the its theater column peaked in frequency before petering out in 1896, the Review was a strong supporter of the Independent Theatre.[4] In commenting on Wilde’s A Woman of No Importance at theAlan’s Wife is not a cheerful play, but . . . we have no right to ask whether a thing is cheerful, or pleasant, or painful, or awe-inspiring. We have but to ask, Is it art? and to deny that Alan’s Wife, with its directness, its exquisite writing, its soul-stirring power, is not a work of art, is simply anathematising tragedy altogether; for if ever true tragedy has been written by a modern Englishman, Alan’s Wife has a right to claim that title. We know but one more powerful play, equally sad and equally simple, Ibsen’s Ghosts; that is all. (708)

The review’s praise of Ghosts further reveals that the Westminster Review was a staunch advocate of the Independent Theatre. William Archer’s translation of Ghosts, a play that shares with Alan’s Wife the theme of a mother euthanizing her child, had been the first production of the Independent Theatre in 1891.

Sharing the Westminster Review’s belief in the value of controversy, Knight explained that although he was not an enthusiast of Ibsen, he nevertheless recognized the importance of Ibsen’s influence because:

In the outcry raised by the production of Ibsen’s quaint, absorbing, perverse, and I fear I must add provincial pieces, the strongest and most spontaneous if most unconscious tribute to his merit is paid. The effect of a bad play is weariness. . . . A man who inspires such admiration and such passion as Ibsen, and who is the subject of nightly discussion and recrimination in literary circles, is not nobody. (Theatrical Notes xv)

Maintaining his sense that popularity is not a good index of cultural importance, Knight specifically identifies “literary circles,” distinct from mass audiences, as arbiters of cultural value. Knight identified specific productions of commercial theaters as works of high culture on par with those produced by European independent theaters: “That the stage is in a more flourishing condition now than at any time in the last half of the century few will deny who recognize that London possesses half-a-dozen theatres able to challenge comparisons with the subventioned houses of the continent” (Theatrical Notes xv-xvi). Similarly, the Westminster Review, which in its comments on Alan’s Wife evinced its partiality to tragedy as a mode of increasing the stage’s cultural capital, praised the commercial production of G. Stuart Ogilvie’s Hypatia, based on Charles Kingsley’s novel, at the Haymarket. Its review claims cultural prestige for drama: “The production of Hypatia at the Haymarket Theatre is an event of more than ordinary importance, as all those who would invest the stage with a special mission in society as a temple of culture will readily admit” (223). The Athenaeum favored Hypatia because it was a history play, and its comparison between Hypatia and Romeo and Juliet reveals the cultural cachet of Shakespeare (31).

Henry Irving’s 1893 production of Alfred Tennyson’s Becket at ![]() the Lyceum was a commercial production that capitalized on the high-culture associations of both Shakespeare and the poet laureate. Because Irving strove to restore cultural status to the British stage while still attracting a popular audience, his production can be viewed as an alternative to the Independent Theatre. Thus, critical responses to Becket’s hybrid nature are particularly revealing. The play, which was heavily revised not only by Irving but also by his leading lady Ellen Terry, strategically drew on the theatrical and historical pasts while simultaneously employing Victorian popular theatrical modes. Becket was inspired by Shakespeare and was written as a history play about Henry II’s appointment of his friend, Thomas Becket, as archbishop of Canterbury, the rift that develops between them as state and church are pitted against one another, and the murder of Becket by the King’s men. These features make it easy to view Becket as an example of the sort of “literary drama” that theater critics such as Archer called for in the 1880s and 1890s (“The Stage and Literature” 219). Indeed, Archer himself praised Becket even as he called it “‘undramatic’ verse,” and the Westminster Review suggested a movement away from commercial valuations when it enigmatically wrote, “The British public is becoming less and less materially minded, more artistic” (Rev. of Becket 346). In addition to Tennyson as poet laureate investing the stage with greater cultural capital, poetry by its very un-theatrical, or even anti-theatrical nature could divest the theater of its commercialism, even in the commercial theater management of Irving’s Lyceum. The Athenaeum praised other poetic dramas such as Tennyson’s “The Foresters,” which was staged by Augustin Daly in

the Lyceum was a commercial production that capitalized on the high-culture associations of both Shakespeare and the poet laureate. Because Irving strove to restore cultural status to the British stage while still attracting a popular audience, his production can be viewed as an alternative to the Independent Theatre. Thus, critical responses to Becket’s hybrid nature are particularly revealing. The play, which was heavily revised not only by Irving but also by his leading lady Ellen Terry, strategically drew on the theatrical and historical pasts while simultaneously employing Victorian popular theatrical modes. Becket was inspired by Shakespeare and was written as a history play about Henry II’s appointment of his friend, Thomas Becket, as archbishop of Canterbury, the rift that develops between them as state and church are pitted against one another, and the murder of Becket by the King’s men. These features make it easy to view Becket as an example of the sort of “literary drama” that theater critics such as Archer called for in the 1880s and 1890s (“The Stage and Literature” 219). Indeed, Archer himself praised Becket even as he called it “‘undramatic’ verse,” and the Westminster Review suggested a movement away from commercial valuations when it enigmatically wrote, “The British public is becoming less and less materially minded, more artistic” (Rev. of Becket 346). In addition to Tennyson as poet laureate investing the stage with greater cultural capital, poetry by its very un-theatrical, or even anti-theatrical nature could divest the theater of its commercialism, even in the commercial theater management of Irving’s Lyceum. The Athenaeum praised other poetic dramas such as Tennyson’s “The Foresters,” which was staged by Augustin Daly in ![]() New York in 1892 (“English Literature in 1892” 24). Moreover, in discussing Swinburne’s play “The Sisters,” which was staged in London in 1892, the Athenaeum not only notes that the audience did not appreciate its poetic qualities, but also specifically identifies the poetic drama as possessing the ability to recapture the lost grandeur of the English stage:

New York in 1892 (“English Literature in 1892” 24). Moreover, in discussing Swinburne’s play “The Sisters,” which was staged in London in 1892, the Athenaeum not only notes that the audience did not appreciate its poetic qualities, but also specifically identifies the poetic drama as possessing the ability to recapture the lost grandeur of the English stage:

Mr. Swinburne’s somewhat structureless tragedy, “The Sisters,” was not generally regarded as a success, though it contained some magnificent lines and several charming songs. There is little doubt, however, that if the author of “Erectheus” and “Mary Stuart” would consent to pay a little more attention to his plots he might give us a modern play of a realistic type that would confer upon the Victorian age some of the prestige that now attaches to the Elizabethan drama alone. (“English Literature in 1892” 25)

Becket, however, is not merely a poetic drama with Shakespearean ambitions. It also employs the melodrama of the popular Victorian stage, particularly in its handling of the conflict between Henry’s wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and his lover, Rosamund, whom Henry had entrusted to Becket’s care. For this reason, other reviews of Becket reflect a conflict between high culture and popular appeal, as many reviewers criticized the play precisely because of its hybrid qualities, but predicted its success because it would appeal to audiences. Archer panned the play’s inclusion of the sub-plot of Queen Eleanor’s murderous rage against Rosamund. Calling it “unhistorical, inconceivable, and profoundly uninteresting,” the critic suggests that

we . . . untwine them in our minds as much as possible, and . . . concentrate on the two or three really noble, moving, and dramatic passages in which Becket commands the stage. The Council at

Northampton and the murder scenes are, of course, the culminating points of the action. It is futile to deny a certain order of dramatic faculty to the man who wrote these scenes. They are very fine examples of that large, pictorial treatment of history which is one of the noblest possibilities of the romantic drama.

This review seeks to separate the high-culture appeal of historical (male) drama from the popular appeal of melodrama in the subplot of female jealousy.

Another crowd-pleasing element of Becket was its staging. Both Rosamund’s and Becket’s transformations during the play are realized visually with striking costume changes. The stage sets, meanwhile, were historical settings with picturesque architecture, many supernumeraries populating the stage, beautifully painted backdrops, and pastoral external scenes (Partridge et al.). The Westminster Budget detailed how “‘Becket’ is a success de spectacle. There is splendidly set out a collection of pictures of England and ![]() Normandy in the time when the Byzantine or Norman architecture touched its full glory to wane in the splendour of the Gothic. Hardly a scene not full of interest” (4). It mentions stage sets in which the combination of three-dimensional architecture combines with painted backdrops to provide an illusion of depth: “the north transept of

Normandy in the time when the Byzantine or Norman architecture touched its full glory to wane in the splendour of the Gothic. Hardly a scene not full of interest” (4). It mentions stage sets in which the combination of three-dimensional architecture combines with painted backdrops to provide an illusion of depth: “the north transept of ![]() Canterbury cathedral, with a chapel on the left, huge arches in the centre borne on massive columns crowned by cushion capitals, and behind two wide flights of steps, both apparently leading to the choir—the whole a triumph of stage pictorial art, and full of majesty,” “a terrace in a Norman castle, with a covered flight of steps leading to a keep, and a vast champaign of pasture land and winding river at the back,” and “a street in Northhampton, framed by a huge arch, through which is seen high, gabled, overhanging houses that lead to a large, towered city gate” (4). Despite its own quibbles with the play, the Budget ultimately concluded: “On the whole, the mounting is so magnificent, the acting of Mr. Irving and Miss Terry so admirable, and the play had such great adventitious interest, that whilst it has been our duty to point out what we deem serious faults, there can be no doubt most people will deem that ‘Becket’ can hold its own in charm with almost any of the Lyceum productions” (6). These are the lavish, spectacular stage sets of Shakespearean histories that Victorian audiences had come to know in the productions of Charles Kean. Such spectacle was popular, but its connection to history and Shakespeare also provided cultural capital for the drama. Therefore, while the Budget reviewer concedes the success of Becket through predicting that others will approve of it, the Westminster Review was more enthusiastic about the production: “Is Lord Tennyson a dramatist? It is certainly not the fault of Mr. Henry Irving and the management of the Lyceum Theatre if he is not; for a more successful drama could not well have been devised. The scenic effects are more artistic, if less gorgeous, than those of Henry VIII, in the production of which it was generally held that the Lyceum had surpassed itself” (345).

Canterbury cathedral, with a chapel on the left, huge arches in the centre borne on massive columns crowned by cushion capitals, and behind two wide flights of steps, both apparently leading to the choir—the whole a triumph of stage pictorial art, and full of majesty,” “a terrace in a Norman castle, with a covered flight of steps leading to a keep, and a vast champaign of pasture land and winding river at the back,” and “a street in Northhampton, framed by a huge arch, through which is seen high, gabled, overhanging houses that lead to a large, towered city gate” (4). Despite its own quibbles with the play, the Budget ultimately concluded: “On the whole, the mounting is so magnificent, the acting of Mr. Irving and Miss Terry so admirable, and the play had such great adventitious interest, that whilst it has been our duty to point out what we deem serious faults, there can be no doubt most people will deem that ‘Becket’ can hold its own in charm with almost any of the Lyceum productions” (6). These are the lavish, spectacular stage sets of Shakespearean histories that Victorian audiences had come to know in the productions of Charles Kean. Such spectacle was popular, but its connection to history and Shakespeare also provided cultural capital for the drama. Therefore, while the Budget reviewer concedes the success of Becket through predicting that others will approve of it, the Westminster Review was more enthusiastic about the production: “Is Lord Tennyson a dramatist? It is certainly not the fault of Mr. Henry Irving and the management of the Lyceum Theatre if he is not; for a more successful drama could not well have been devised. The scenic effects are more artistic, if less gorgeous, than those of Henry VIII, in the production of which it was generally held that the Lyceum had surpassed itself” (345).

Even so, the avant-gardism of the Westminster Review relative to the Athenaeum is evident in the fact that the Review praised Becket for its “originality in design,” emphasizing that its innovative dramatic qualities, rather than the characteristics of its production, would lead to its endurance:

we should be inclined to say that as an acting play, Becket in the future will be crowned with a far more real success than has been accorded to Shakespeare’s Lear. The frequent plaudits in a crowded house betokened a deep-felt interest in all that was passing—an interest which implied something else besides any mere satisfaction of curiosity that could be supplied by luxurious upholstery, scenic art, or even clever acting. (345-46)

The review, however, depicts the audience’s plaudits as ephemeral and inconstant:

What is held to be undramatic in one age is considered quite the reverse in the next, not out of any disrespect for the judgment of the earlier date, but simply that the tastes and feelings of the public are different, and the writer has lived before his time. We all know that Shakespeare was spoken of in the last century in terms anything but flattering, and at the present time his works are not so popular as they were ten years ago. They are becoming a little used up, and the appetite for fresh matter, style, and ideas is now so voracious that it becomes the severest tax upon the resources at the command of the acting manager to obtain the materials for plays which will be calculated to satisfy this craze of the public for what is new and what is original. (345-46)

Yet even as the review questions both the preeminence of Shakespeare and the distinction of originality, it claims for Becket a place in the dramatic canon. More significantly, while audience taste may be ephemeral, the review, “notwithstanding all that has been written, and all that has been said upon the Tennysonian drama,” claims for itself the position of arbiter of canonicity: “in our humble opinion Becket is not only a poem of beautiful versification, but is also a drama, of a special and distinctive character we admit, but nevertheless one that will make its way inevitably into the store-rooms of English dramatic literature” (346).

At the same time that theater critics elevated themselves as a specialized class of theatergoer, they elevated late-Victorian dramas above their popular mid-century predecessors. To this day, no earlier-century dramas remain as commonly in print and in production as the late-Victorian works of Shaw, Wilde, and Ibsen. As Jackie Bratton has argued, our understanding of the Victorian theater has been shaped by Victorian cultural forces that were not disinterested but rather cast the theater in particular cultural roles. Whether theater critics in the early 1890s distinguished themselves and the theater through a conservative interest in past forms or by supporting path-breaking innovation, their reviews reveal the cultural work performed by theater critics, who helped to define the late-nineteenth-century theater as a conflict between the commercial and popular stage in opposition to avant-garde and independent theater companies, and leant cultural influence to the latter. Their work undoubtedly helped shape twentieth- and twenty-first-century generalizations not only about Victorian drama, but also about Victorian theater audiences—generalizations that demand investigation such as that of the fine-grained analysis performed Jim Davis and Victor Emeljanow. Critics’ adoption of the terms of non-commercialism helped to redefine the world of the theater from one of popular entertainment to one that had greater cultural cachet. They themselves defined the 1890s as a significant break from earlier Victorian theater and the beginning of a new era for British drama.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published February 2013

Miller, Renata Kobetts. “The Cultural Work of Drama Criticism in the Early 1890s.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Archer, William. “The Free Stage and the New Drama.” Fortnightly Review n.s. 50 (1891): 663-72. Print.

—. “The Stage and Literature.” Fortnightly Review n.s. 51 (1892): 219. Print.

[Archer, William.] Rev. of Becket. The World 15 February 1893. Print.

Barrett Browning, Elizabeth. Aurora Leigh. 1856. Intro. and notes Kerry McSweeney. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1993. Print.

“‘Becket’ at the Lyceum.” The Westminster Budget 9 February 1893. Print.

Bratton, Jacky. New Readings in Theatre History. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

[Collins, Wilkie.] “Dramatic Grub Street: Explored in Two Letters.” Household Words 17 (1858): 265-70. Print.

Davis, Jim and Victor Emeljanow. Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840-1880. Hatfield, Hertfordshire: U of Hertfordshire P, 2001. Print.

“The Drama.” Westminster Review 139:1 (1893), 104-8. Print.

“The Drama. Westminster Review 139:1 (1893), 223-38. Print.

“The Drama.” Westminster Review 139:2 (1893), 346-48. Print.

“The Drama.” Westminster Review 139:1 (1893), 706-8. Print.

“English Literature in 1892.” Athenaeum (1893:1), 19-24. Print.

Francis, John Collins. Notes by the Way with Memoirs of Joseph Knight , F.S.A.: Dramatic Critic and Editor of ‘Notes and Queries,’ 1883–1907 and the Rev. Joseph Woodfall Ebsworth, F.S.A. Editor of the Ballad Society’s Publications (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1909). Wikisource. Web. 11 April 2012. <http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Notes_by_the_Way.djvu/31>.

Gates, Joanne E. Elizabeth Robins, 1862-1952: Actress, Novelist, Feminist. Tuscaloosa and London: U of Alabama P, 1994. Print.

Gilcher, Edwin. A Bibliography of George Moore. DeKalb: Northern Illinois Press, 1970. Print.

Grein, J. T. Interview. Chronicle. Clipping in Michael Field’s journals. British Library Add. MS 46781, vol. 6 (1893). Print.

John, Angela V. Elizabeth Robins: Staging a Life, 1862-1952. London and New York: Routledge, 1995. Print.

Knight, Joseph. Theatrical Notes (London: Lawrence and Bullen, 1893). Google books. 11 April 2012.

[Knight, Joseph]. “Drama.” Athenaeum (1873: 1), 57-8. Print.

—. “Drama.” Athenaeum (1873: 1), 543-45. Print.

—. “Drama.” Atheneaum (1873: 1), 576-77. Print.

—. “Drama.” Athenaeum (1883:1), 61-2. Print.

—. “Drama: The Week.” Athenaeum (1893:1), 31-2. Print.

—. “Drama: The Week.” Athenaeum (1893:1), 131-132. Print.

—. “Drama: The Week.” Athenaeum (1893:1), 451-52. Print.

—. “Dramatic Gossip.” Athenaeum (1873: 1), 123-24. Print.

—. “Dramatic Gossip.” Athenaeum (1893:1), 228. Print.

Mazer, Cary M. “New Theatres for a New Drama.” The Cambridge Companion to Victorian and Edwardian Theatre. Ed. Kerry Powell. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004: 207-21. Print.

Moore, George. Impressions and Opinions. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891. Print.

Partridge, J. Bernard, W. Telbin, J. Harker, and Hawes Craven, illus. Souvenir of Becket by Alfred, Lord Tennyson: First Presented at the Lyceum Theatre, 6th Feb., 1893 by Henry Irving. London: George Bell and Sons, 1904. Print.

Postlewait, Thomas. Prophet of the New Drama: William Archer and the Ibsen Campaign. Contributions in Drama and Theatre Studies, 20. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1986. Print.

Walkley, A. B. “Some Plays of the Day.” Fortnightly Review n.s. 52 (1893), 468-76. Print.

Watts, Theodor. “Tennysoniana.” Athenaeum (1893), 154. Print.

ENDNOTES

Support for this project was provided by a PSC-CUNY Award, jointly funded by The Professional Staff Congress and The City University of New York. I am grateful to Jim Davis for his thoughts on this essay, and to the members of the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals for their suggestions and collegial support at the Society’s 2011 conference in ![]() Canterbury.

Canterbury.

[1] A notable example of the Victorian view that drama was corrupted by the need to appeal to a mass audience is Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1856), in which the eponymous poet describes how drama is by its very nature more responsive to audience demands. According to Aurora, in contrast to poetry, drama

Makes lower appeals, submits more menially,

Adopts the standards of the public taste

To chalk its height on, wears a dog-chain round

Its regal neck, and learns to carry and fetch

The fashions of the day to please the day,

Fawns close on pit and boxes, who clap hands

Commending chiefly its docility

And humour in stage-tricks—or else indeed

Gets hissed at, howled at, stamped at like a dog,

Or worse, we’ll say. (154-55)

Wilkie Collins, in “Dramatic Grub Street” (1858) more specifically execrates the lack of discrimination in the broad-based, working-class audience of the Victorian theater. According to Collins, theater managers cater to a

vast nightly majority . . . whose ignorant sensibility nothing can shock. Let him cast what garbage he pleases before them, the unquestioning mouths of his audience open, and snap at it. . . . If you want to find out who the people are who know nothing whatever, even by hearsay, of the progress of the literature of their own time—who have caught no vestige of any one of the ideas which are floating about before their very eyes—who are, to all social intents and purposes, as far behind the age they live in, as any people out of a lunatic asylum can be—go to a theatre, and be very careful, in doing so, to pick out the most popular performance of the day. (269)

[2] “Théâtre Libre,” which originally appeared in the Hawk on June 24, 1890, as “The New Théâtre Libre,” is reprinted in Moore’s collection of essays, Impressions and Opinions. See also Moore, “Our Dramatists and Their Literature,” “Note on ‘Ghosts,’” and “On the Necessity of an English Théâtre Libre,” in Impressions and Opinions, 181-214, 215-26, 238-48. These essays originally appeared under different titles in periodicals. For details about the original publication of these essays, see Edwin Gilcher, A Bibliography of George Moore.

[3] The theater reviews in the Athenaeum are unsigned. In Notes by the Way, John Collins Francis, who was the son of Athenaeum publisher John Francis, identifies Joseph Knight as the drama critic for the Athenaeum beginning in 1869. Knight’s own Theatrical Notes, a collection of his earlier reviews that promises a second volume of more recent columns, is written from the vantage point of drama critic for The Athenaeum. The second volume was never published.

[4] The regular theater column of the Westminster Review reached its height in 1892 and 1893, with eight columns each of those years. In 1894 the column appears once a month between January and June before vanishing. For the rest of the century, there is only one column in 1895 (in December) and one column in 1896 (in January).

[5] The relationship between Archer and Robins is a source of debate among biographers. Joanne Gates allows that the two loved each other, yet holds that “Archer’s own sense of propriety and his own dedication to a lasting creative relationship suggest that their intimacy was not sexual despite temptation to make it so in the early stages” (53). Angela John and Thomas Postlewait, however, have marshaled compelling evidence that the deep love that the two shared over many years did include a sexual relationship and that Robins may even have been pregnant with Archer’s child.