Abstract

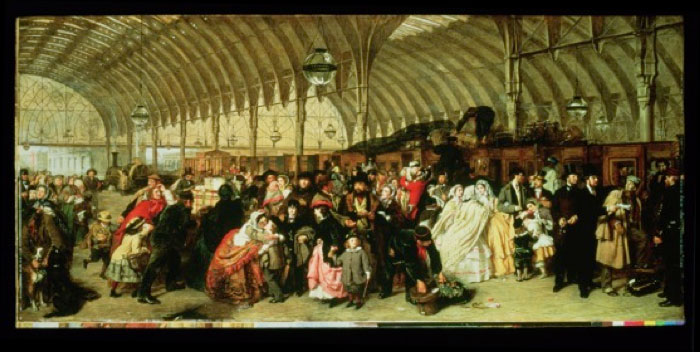

William Powell Frith’s oil painting, The Railway Station (1862), is an enlightening case study of the pressures and conditions that formed an art viewer in the second half of the nineteenth century in London. A painting of a contemporary urban crowd, displayed for that same crowd in a novel single-picture exhibition, has much to tell us about the emergence of modern structures of seeing and living based on new configurations of money, time, and space.

Ducking out of the bright daylight of the

The way in which Frith’s painting was exhibited illustrated several typical aspects of Victorian art viewing: 1. The single-picture show organized by the newly prominent art dealer engaging in speculative investment; 2. An interested public who felt personally involved through the purchase of prints by subscription; and 3. A type of viewing that involved reading a picture via its narrative details as a form of entertainment.

The Jewish art dealer Louis Victor Flatow (variant spelling Flatou) exhibited the work in the fall of 1862, in what was termed “one of the boldest speculations even in this speculative age” (Art Journal 1862, 147). Most newspapers reported Flatow’s expense as £8,750, trumpeting it as the highest sum ever paid to an artist for a single artwork. It was actually closer to £5250: As Pamela Fletcher notes in “On the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in London” (Fletcher, “On the Rise” n. pag.), Flatow first arranged for the purchase of preliminary sketches, the work itself, and reproduction rights for £4500, eventually demanding the exhibition rights as well for an additional £750. This sort of transaction and the publicity surrounding it promoted artist, picture, and dealer, as Flatow became a significant character in the story. The Art Journal noted in a preview of what it described as “a great national work,” that “as Mr. Flatou is known to be a gentleman of sound practical knowledge, as well as a thorough critic in modern Art, in which he is an extensive and successful dealer, we presume he has taken into wise account his chances of gain or loss by the transaction.” About Frith’s contribution, it was reported with some exaggeration that “the picture is ten feet in length. . . . he has, we understand, been during many years making studies for it, having long looked forward to the theme that was calculated to extend and establish his well-earned fame.” This journalist described Frith as “a man of rare genius and of matured knowledge in all that pertains to Art” (Art Journal 1861, 61).

Much was at stake in terms of the artist and dealer’s reputations and finances, a gamble that paid off when The Railway Station became one of the must-see sensations of the season, drawing up to 1,000 people per day and a rumored total of 80,000 over the course of its run (Athenaeum 793; Art Journal 1862, 210). Frith himself estimated attendance at 21,150 (Frith 1.225). Such volume speaks to the newly expanded art public in an era of increased consumption of consumer and luxury goods. The art dealing profession was thriving, and as Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich have found, London was a major center for the art market (5). Flatow used The Railway Station, which he commissioned in deliberate competition with dealer Ernst Gambart, to raise his profile and his income, which he did quite successfully for a year until his death in 1863 (Rubenstein 284). Frith describes Flatow’s irritatingly persistent salesmanship with a mixture of admiration and anti-Semitic stereotyping: “Flatow was triumphant; coaxing, wheedling, and almost bullying, his unhappy visitors. Many of them, I verily believe, subscribed for the engraving to get rid of his importunity.” The artist went on to describe the purchaser as a “victim” and Flatow as a “betrayer” (Frith 1.225).

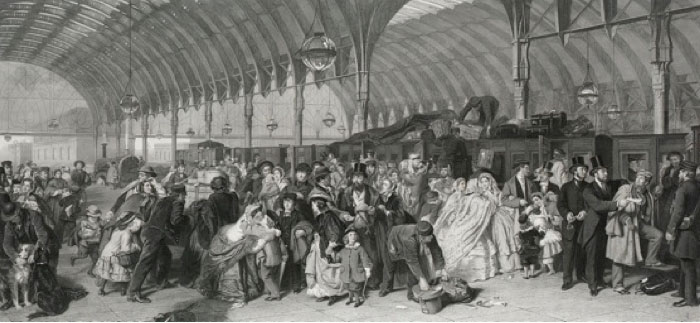

The picture was sold to Henry Graves & Co., who produced the official engraving after the work in 1866, done by artist Frank Holl (Fig. 2). The newspapers of the day make claims that the price paid to Flatow by the engraver was as much as £24,000 (Art Journal 1869, 159). Graves in turn said that he paid a total of £18,400: £16,300 for the painting and the list of subscribers and £2100 to buy out a previously contracted engraver (Belfast News-Letter n. pag.).

The Railway Station was therefore an experiment in modernity through the manner in which it was produced and marketed, its dependence on media promotion, and the mass sales and distribution of reproductions. Purchasing a black and white print reproduction in advance of its existence, the public became involved in the process as investors in both painting and print. As the Times commented about Flatow’s ploy: “The subject and price of Mr. Frith’s picture alike belong to the time. The one is typical of our age of iron and steam; the other is only possible in a period of bold speculating, enterprising publishers and picture dealers, [and] a large print-buying and picture-seeing public” (The Times qtd. in Taylor 31). The painting, produced on commission by a dealer willing to take a gamble on his profits, became a leap of capitalist faith. At the very center of the composition, in fact, is an outstretched palm of a cabbie demanding money (Fig. 3), acknowledging the importance of financial exchange as a generator of the picture. And not surprisingly, in the background to the right (Fig. 4), Flatow himself is portrayed in the painting having a discussion with the engineer; the dealer, together with the “driver”—Frith—makes the “train”—the artistic production—run. According to Frith’s daughter, Flatow said he had actually wanted to be the “hengine driver” because “after all, it’s my money will make the pictur’ go” (Panton 119).

Appearing in a private gallery rather than the ![]() Royal Academy, The Railway Station was not subject to a preliminary assessment by the elite art world but rather put directly before the public, who literally bought into it and made it possible through their financial support; they were therefore, as one critic commented, the true patrons of contemporary artworks such as this one (Chambers’s 404). Moreover, as Tom Taylor declared in a pamphlet written for the exhibition of The Railway Station, the artist “in choosing such a subject, makes every spectator his critic” (5). That is, most of the picture’s viewers would have had direct experience with the scene portrayed, or if they did not, they were free to inspect

Royal Academy, The Railway Station was not subject to a preliminary assessment by the elite art world but rather put directly before the public, who literally bought into it and made it possible through their financial support; they were therefore, as one critic commented, the true patrons of contemporary artworks such as this one (Chambers’s 404). Moreover, as Tom Taylor declared in a pamphlet written for the exhibition of The Railway Station, the artist “in choosing such a subject, makes every spectator his critic” (5). That is, most of the picture’s viewers would have had direct experience with the scene portrayed, or if they did not, they were free to inspect ![]() Paddington Station, London—the setting of the picture—for themselves at any time. The realist, detailed style of the work, suggesting a plausible and convincing transcription of an actual event, both asserted its truth value and at the same time addressed those who could verify its credibility. Visitors to the exhibition therefore felt empowered by their own expertise concerning the appearance of modern London and its rail stations: “I heard at least a score of people remark on the fidelity with which Mr. Frith had reproduced the features of the Great Western officials,” commented one viewer of the exhibition (Chambers’s 404). The “popularity” of this picture, in every sense of the word, created a great stir of publicity. Catering to the middle class, generating mass support, produced on speculation, the painting in fact resembled aspects of the railroads themselves.

Paddington Station, London—the setting of the picture—for themselves at any time. The realist, detailed style of the work, suggesting a plausible and convincing transcription of an actual event, both asserted its truth value and at the same time addressed those who could verify its credibility. Visitors to the exhibition therefore felt empowered by their own expertise concerning the appearance of modern London and its rail stations: “I heard at least a score of people remark on the fidelity with which Mr. Frith had reproduced the features of the Great Western officials,” commented one viewer of the exhibition (Chambers’s 404). The “popularity” of this picture, in every sense of the word, created a great stir of publicity. Catering to the middle class, generating mass support, produced on speculation, the painting in fact resembled aspects of the railroads themselves.

It was also its very popularity that made the work controversial. “Mr. Frith’s picture is really a poor affair,” groused London Review, “popular as is the subject, popular the artist, and popularity-hunting the devices which have been and will be adopted to make the work a ‘screaming success’—screaming as a railway whistle” (392). The public enthusiasm for the work made it questionable as fine art. Noted a critic, “If the artist were successful in production of a popular work, the exhibition of which would be generally attractive, the speculation might be remunerative. But the very fact that such elements of popularity were essential to its financial success somewhat imperilled its character in an artistic sense” (Art Journal 1862, 122-3). The equivocal position of Frith’s painting somewhere between high art and sensational entertainment was clear from an article in Chambers’s Journal listing “the Flying Man,” Charles Dickens reading David Copperfield, and Frith’s painting as equivalent attractions (404).

Those who attended Frith’s one-picture exhibition were availing themselves of a complex multi-layered opportunity: most of all to be entertained by seeing themselves in representation but also to experience a social event endowing them with a particular form of cultural capital, and finally, to absorb the artist’s genius. Ironically, although the one-picture exhibition both fed upon and helped invent the notion of the individual genius, The Railway Station involved many producers. W. Scott Morton contributed to the work by painting the architectural details of Paddington Station (Chapel 90). An article in Photographic News announced that Frith also relied on photographs, as another nod to modern technology: “Mr. Samuel Fry [is] engaged in taking a series of negatives 25 x 18 inches and 10 x 8 inches of the interior of Great Western Station, engine, carriage, &c., for Mr Frith, as aids to the production of his great painting Life at a Railway Station. Such is the value of the photograph in aiding the artist’s work, that he wonders now how he ever did without them!” (Photographic News 204). The Railway Station, then, was a collaborative production.

Figure 5: William Holman Hunt, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860, oil on canvas, Birmingham Museum and Art Galleries)

Viewers were entranced by the novel method of display and happily bought into the myth it helped to produce. Encountering a single painting in a luxurious environment such as Flatow’s was a relatively new experience, as this form of exhibition had only recently come to prominence with such works as William Holman Hunt’s Finding of the Savior in the Temple (Fig. 5) in 1860, which appeared in Gambart’s German Gallery and subsequently traveled to the UK and ![]() Ireland (Bronkhurst, 1.173-177). Indeed, at the same time that The Railway Station appeared at the

Ireland (Bronkhurst, 1.173-177). Indeed, at the same time that The Railway Station appeared at the ![]() Haymarket, Ernest Gambart’s

Haymarket, Ernest Gambart’s ![]() French Gallery in Pall Mall was exhibiting Frith’s Derby Day (fig. 6) (The Standard 3). Individual pictures began to go on tour like musicians or lecturers, and Derby made a circuit in

French Gallery in Pall Mall was exhibiting Frith’s Derby Day (fig. 6) (The Standard 3). Individual pictures began to go on tour like musicians or lecturers, and Derby made a circuit in ![]() Australia (Montana). The Railway Station itself toured Ireland in 1863 (The Belfast News-Letter n. pag.).

Australia (Montana). The Railway Station itself toured Ireland in 1863 (The Belfast News-Letter n. pag.).

These one-picture events were popular in Victorian London, producing—and produced by—new expectations of art viewers, particularly regarding the type of focus required at an exhibition. An encounter with an artwork was to be experienced through time, and a type of prolonged viewing very different from our more casual glancing of today. One review of the Royal Academy show in 1872, for instance, advised that a viewer should spend ten minutes before a picture: “let him think himself into the picture till its life speaks out of it. He will soon find that there is something human in it when it does begin to speak, that a picture, like a man or woman, opens out wonderfully upon better acquaintance, always changing” (Morley 695).

Viewing the picture was also accompanied by reading a pamphlet written by playwright and art critic Tom Taylor, who seems to have consulted directly with Frith himself. This description helped visitors to Flatow’s gallery decipher the painting’s many scenes taking place on the platform of the Great Western Railway. On the far right of the work is the arrest of a criminal (Fig. 7). Next to this incident is a wedding party in which newlyweds take leave of bridesmaids and family. To the left is a foreign couple confused by the vehement solicitations of a hansom cab driver seeking a higher tip. And in the center a family sends its boys to school. An episode like the one depicted here may very well have occurred in the artist’s own life, as in 1861 his two eldest sons, who modeled for the picture, William Powell and Charles George, were schoolboys in Somerset, the terminal for which was Paddington Station (1861 Census). Behind this family appears a much more harassed family group in a rush (Fig. 8).

The Great Western Railway train itself stretches into the distance on the right, getting up steam and accepting a wide range of passengers from different walks of life struggling with luggage and taking leave of each other before the departure to “Southampton, Portsmouth, or ![]() Plymouth,” according to Taylor (5). Though they travel for an array of purposes, including tourism, education, escape from justice, military or naval service, health, and sport, the people are yet united in their need to catch the train at an exact and predictable scheduled time. Out of the confusion on the platform will gradually emerge a coherent unified mass. And not only will the disorderly become ordered, it will also be conveniently categorized according to class; the words “First Class” are legible on one of the carriages. The train was recognized as a “mixed down” train, consisting of first, second, and third class carriages (Illustrated London News 457). The chaotic crowd will be tidied and sorted into different class carriages in the train itself and borne through the countryside by an engine titled “Great Britain,” much as the new English style of modular glass and iron architecture orders the painting itself.

Plymouth,” according to Taylor (5). Though they travel for an array of purposes, including tourism, education, escape from justice, military or naval service, health, and sport, the people are yet united in their need to catch the train at an exact and predictable scheduled time. Out of the confusion on the platform will gradually emerge a coherent unified mass. And not only will the disorderly become ordered, it will also be conveniently categorized according to class; the words “First Class” are legible on one of the carriages. The train was recognized as a “mixed down” train, consisting of first, second, and third class carriages (Illustrated London News 457). The chaotic crowd will be tidied and sorted into different class carriages in the train itself and borne through the countryside by an engine titled “Great Britain,” much as the new English style of modular glass and iron architecture orders the painting itself.

Indeed, as the title suggests, the railway was central to the meaning of the picture. Despite the apparent foregrounding of the crowd, critics were quick to suggest that the painting meditated on the awesome power of man’s technological innovation—that is, on modernity itself, since so many things about the railway were new that its invention seemed to many to mark out a new era (Thackeray 64). The train station itself was a distinctively modern, English building type; as a writer for the Building News described railway termini in 1875, they represented “the only real representative kind of building we have” (Building News 1875 93). Innovative use of glass and iron building materials allowed walls and roofs to become surfaces that marked off space rather than remaining obdurate forms in themselves, creating structures that emphasized line over mass and filtered light in new ways. Historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch has noted that a lack of dramatic light contrasts within the space of the station contributed to the novel effect by removing the traditional benchmarks by which people had estimated interior size and distance. Frith’s overall illumination suggests an attempt to capture this effect (Schivelbush 50-55).

As the Illustrated London News propounded, “The railway has now infinitely varied relations with English life. It is the grandest exponent of the enterprise, the wealth, and the intelligence of our race. The iron rails are welded into every life-history, and sometimes interwoven with our very heartstrings. The steam-engine is the incarnate spirit of the age—a good genius to many, an evil demon to some” (Illustrated London News 457). In his pamphlet, Taylor reminded readers of the importance of railroads’ influence in this regard by citing William Wordsworth’s belief that railroads suggested “the conquest of space” (3). As scholars have noted, train travel produced a radical reorganization in concepts of space and time (Schivelbusch 44). Altering routes, shortening travel times and bringing formerly remote communities in contact with cities—and with London in particular—the railway remapped the world. Space itself shrank due to new estimations of how long it took to traverse, resulting in the proliferation of leisure travel such as that enjoyed by the fisherman in The Railway Station. Furthermore, scattered throughout the crowd are newsboys hawking the Daily Telegraph, reminding us that the world is smaller too as a consequence of the modern invention of both the telegraph and the newspaper.

Time is also a major theme in Frith’s picture, in which, as noted, various groups and vignettes are all unified by the shared goal of punctually boarding the train. Trains also forever changed British consciousness by standardizing times nationwide through the imposition of schedules. As late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century sociologist Georg Simmel observed, this new importance of time developed alongside market capitalism, which similarly placed a new value on temporal units. In Frith’s picture, we see individuals obeying the new dictates of “clock time,” an urban capitalist phenomenon linked to the rise of factories and opposed to “agrarian time” (Simmel in Harvey 6). The Railway Station was a novel mode of using the structures of modernity itself to unite people in a picture manifestly about the present and about time itself (Arscott).

Frith portrays plainclothes detectives, visible only at the moment they step forward to act in a punitive fashion. Modeled on the real figures of James Brett and Michael Haydon, the detectives demonstrate their renowned, finely-honed faculties for identifying and apprehending the dangerous elements of society. The Illustrated London News identified Haydon as the individual holding the handcuffs and Brett as the man with the sealed warrant, adding that this pair had “discovered the gold-dust robbery, brought Hughes from Australia, traced Kiss all over the continent to ![]() Venice, and discovered the Guinness-Hill lost child of fortune” (457).

Venice, and discovered the Guinness-Hill lost child of fortune” (457).

Moreover, the moment that the law appears, we experience a satisfying sense of narrative closure, since the criminal’s plot so clearly ends in justice. Such close reading of pictures was common in the Victorian period. One reviewer actually observed the compositional balance Frith arranged between the so-called “modern bloodhounds” (Critic 397) on the right side of the picture and the actual hunting dogs on the far left, attended by a gamekeeper and shackled together in much the same way the detectives handcuff the criminal (Morning Herald 3). Victorian viewers were accustomed to look for tiny parallel occurrences in images. In his treatise on pictorial composition, for example, Henry Peach Robinson illustrated what he termed the “law of repetition” with David Wilkie’s First Earring of 1835 (Fig. 9), in which the dog scratches his ear in empathy with the little girl in the central vignette (75). Viewers understood that the theme of discipline and control of the animal or the unruly framed this work and, implicitly, the public sphere that it represented.

Frith’s composition itself also places stark moral extremes in direct juxtaposition. It includes both light and dark areas, which correspond to the moral valence of the events taking place in them: Directly next to the vignette of the arrest of the criminal is a happy bride in yellow taking leave of her bridesmaids to start her new life with her husband. Such an arrangement was perceived and appreciated by Frith’s audience: “So it is that the darkest shadows and brightest lights of life come together; that joy is intensified by sorrow, and sorrow deepened by joy, as the painter uses his darks and lights to relieve each other” (Taylor 9). Another reviewer perceived “two extremes of pictorial almost as much as moral light and shade” (Daily News 2). In this obvious contrast, Frith drew on elements of melodrama, a literary form based on the stark polarization of good and evil. As Peter Brooks has observed in The Melodramatic Imagination, “cops and robbers fiction” and similar genres are forms of realism that insist that reality can be exciting rather than mundane. He posits that the psychological function of melodrama is to compel the viewer to experience a sense of wholeness in response to the simpler emotions of the depicted characters. According to Brooks,

melodrama comes into being in a world where the traditional imperatives of truth and ethics have been violently thrown into question, yet where the promulgation of truth and ethics, their instauration as a way of life, is of immediate, daily, political concern. . . . We may legitimately claim that melodrama becomes the principal mode for uncovering, demonstrating, and making operative the essential moral universe in a post-sacred era. (15)

The Railway Station created a reassuring sense of an intact, integrated self in its viewers, insisting on the modern world as a place of truth and justice.

The picture also conveyed notions about race to its audience, producing and reinforcing some dominant beliefs. Frith’s England is one of racial hierarchy dominated by whiteness. In the center of the painting, Frith contrasted Englishness and generic “foreignness,” a disparity noticed by reviewers. “In immediate conjunction with [Frith’s own family] we have a coarse and darkly complexioned foreigner, deeply tinged, as it would appear, with African blood, but richly bedizened in jewelry and furs,” commented the Observer (6). The reference to “African blood” was an extreme way of suggesting the difference of the man, and of underscoring that he was as unlike the whiteness of Frith’s pure English family as possible (the foreigner was variously interpreted as Italian, South American Spanish, French, and German) (Taylor 13; The Critic 397; Daily News 2). As another reviewer claimed, Frith “impersonates paterfamilias capitally with his fair, ruddy, Saxon face, buttoning up his coat and his feelings at parting with his two elder boys . . . Materfamilias [is] perfect as such in her motherly comeliness.” Pater and mater are equated with fairness, beauty, and emotional restraint. As the viewer realizes, not only is the bearded man most likely being cheated by the canny British cabdriver, he is also henpecked, incapable even of sustaining the appropriate power relations between a man and his wife. Taylor contrasted the “sturdy cabman” of “British bull-doggedness” with the poor foreigner who “has no knowledge nor will of his own,” claiming that “the fair-haired Signora is the head of the family to all intents and purposes” (13-14). Unlike the dubious foreigner and his problematic marriage with a dominating shrew, or the criminal whose horrified wife witnesses his arrest from the door of the railway carriage, the bourgeois gentleman at the center of the canvas is the proper pater. Further emphasizing the harmony in his own central group, Frith contrasts it with the badly organized, vulgar family to the left, in which a florid mother irritably tows along her children while giving nervous directions about her luggage. The criminal, as well, was interpreted as not entirely white: “In the face of the detected swindler, whose expression is the only discordant part of the picture, we perceive with some satisfaction that the man is of a different race from our own. There is a strong African tinge about his physiognomy” (Saturday Review 622). Such juxtapositions reinforced the central position and superiority of the white British middle-class family, defining the members of such a family in contrast with the foreign, dark-skinned, humorous, disempowered, or disorderly.

In another gambit that both instructed people in how to see and relied on their preconceptions, Frith included such physiognomical stereotypes as the thug, recognizable by his low forehead and brutish face, standing behind the bridal grouping with his cane to his mouth (Fig. 10). In the brochure for the picture, Taylor described his “low brow, flattened nose and gapped teeth” and drew attention to his “seal-skin cap and tweed coat,” noting that he was probably a “costermonger, choice fruit of ![]() Westminster slums” and possibly a burglar as well, since “low excess has written and stamped the character in every line of his face” (Taylor 12-13). Other reviewers drew on this same combination of dress and appearance to recognize the repulsive nature of this figure (Daily News 2; Illustrated London News 457). As suggested by the ease with which the character was categorized, pre-existing notions of what moral and immoral human beings looked like allowed the artist to communicate with his viewers at the same time he consolidated certain stereotypes through repetition of them.

Westminster slums” and possibly a burglar as well, since “low excess has written and stamped the character in every line of his face” (Taylor 12-13). Other reviewers drew on this same combination of dress and appearance to recognize the repulsive nature of this figure (Daily News 2; Illustrated London News 457). As suggested by the ease with which the character was categorized, pre-existing notions of what moral and immoral human beings looked like allowed the artist to communicate with his viewers at the same time he consolidated certain stereotypes through repetition of them.

The Railway Station, exhibited at the Haymarket Gallery in 1862, thematized modernity in its modes of production and reception, as well as in its subject matter. The gallery space itself, thronged with people, mobilized notions of contemporary urban crowd behavior and surveillance, inculcating skills related to effective participation in London public life. Moreover, its realist, narrative style produced a spectator who read in detail while understanding art viewing as a form of social entertainment. Both painting and exhibition created viewers aware of their roles as public performers in—and authoritative, careful scrutinizers of—the contemporary crowd, the legibility of which, it seemed, might be grasped by the initiated.

Linked article: Pamela Fletcher, “On the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in London.” http://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=pamela-fletcher-on-the-rise-of-the-commercial-art-gallery-in-london. For more on Victorian London art galleries, see also Fletcher and Helmreich’s digital London Gallery Project at http://learn.bowdoin.edu/fletcher/london-gallery/index.html

published January 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Marshall, Nancy Rose. “On William Powell Frith’s Railway Station, April 1862.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

This article is drawn in part from my article “Family Affair: Realism, Detection and the Family in William Powell Frith’s The Railway Station of 1862,” British Art Journal 26 (Summer, 2007) and from my book City of Gold and Mud: Painting Victorian London (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Reviews and Announcements: The Railway Station

Art Journal (1861): 61.

Art Journal (1862): 210.

Art Journal 1869, 159.

Athenaeum, 14 June 1862, 793.

Belfast News-Letter, 30 July, 1863, npn.

Building News (1875). In David Thomson, England in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Penguin, 1978.

Chambers’s Journal (1862): 404-406.

The Critic, 19 April 1862, 397-8.

Daily News, 18 April 1862, 2.

Illustrated London News, 3 May 1862, 457.

London Review, 26 April 1862, 392-3.

Morning Herald, 17 April 1862, 3.

Observer, 20 April 1862, 6.

Photographic News, 26 April 1861, 204.

Times, 19 April 1862, cited in Taylor, The Railway Station, 31.

Saturday Review, 31 May 1862, 621-623.

The Standard, 17 April 1862, 3.

1861 Census records.

Scholarship

Arscott, Caroline. “William Powell Frith’s The Railway Station: Classification and the Crowd.” William Powell Frith: Painting the Victorian Age. Eds. Mark Bills and Vivien Knight. New Haven: Yale UP, 2006. 79-94. Print.

Bronkhurst, Judith. William Holman Hunt, A Catalogue Raisonné. Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. London: Yale UP, 2006. Print.

Brooks, Peter The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. New Haven: Yale UP, 1976. Print.

Chapel, Jeanne. Victorian Taste: The Complete Catalogue of Paintings at the Royal Holloway College. London: A. Zwemmer, 1982. Print.

Fletcher, Pamela and Anne Helmreich. “Introduction.” The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London: 1850-1939. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2012. 1-23. Print.

Frith, William Powell. My Autobiography and Reminiscences. London: Richard Bentley, 1888. Print.

Montana, Andrew. “From the Royal Academy to a Hotel and Kapunda: The Tour of William Powell Frith’s Derby Day in Colonial Australia.” Art History 31 (Nov. 2008) : 5, 754–785. Web. 5 January 2015.

Morley, Henry. “Pictures at the RA.” Fortnightly Review 11 (1872): 692-704. Print.

Panton, Jane Ellen Frith. Leaves from a Life. London: Eveleigh Nash, 1908. Print.

Robinson, Henry Peach. Pictorial Effect in Photography. London: Piper & Carter, 1869. Print.

Rubenstein, William D. The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print.

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. The Railway Journey: Trains and Travel in the Nineteenth Century. Trans. Anselm Hollo. New York: Urizen, 1979. Print.

Simmel, George. In David Harvey, Consciousness and Urban Experience: Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanization. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1985.

Taylor, Tom. The Railway Station. London: Henry Graves, 1865. Print.

Thackeray, William Makepiece. “De Juventute.” 1860. The Roundabout Papers, The Works of William Makepeace Thackeray, 1910-11, Vol, XX, 73. The Bourgeois Experience, Victoria to Freud, vol. 1: Education of the Senses. Ed. Peter Gay, Oxford: Oxford UP, 1984. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Paul Fyfe, “On the Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, 1830″