Abstract

This essay gives a brief overview of the events of 26-27 August 1883, when the volcanic island of Krakatoa in Indonesia exploded; it generated tsunamis which killed over 36,000 people, was heard 3,000 miles away, and produced measurable changes in sea level and air pressure across the world. The essay then discusses the findings of the Royal Society’s Report on Krakatoa, and the reports in the periodical press of lurid sunsets resulting from Krakatoa’s dust moving through the atmosphere. It closes by examining literature inspired by Krakatoa, including a letter by Gerard Manley Hopkins, a poem by Alfred Tennyson, and novels by R. M. Ballantyne and M. P. Shiel.

On 27 August 1883, after a day of alarming volcanic activity, an obscure, uninhabited island now widely known as ![]() Krakatoa (or Krakatau)[1] erupted with a force more than ten thousand times that of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima (Thornton 1). The world quickly took notice. Officials reported the eruption via undersea telegraph cables. People thousands of miles away heard the explosion, and instruments around the world recorded changes in air pressure and sea level. In the months that followed, newspapers and journals printed vivid accounts of spectacular sunsets caused by fine particles that the volcano spewed into the upper atmosphere and that circled the globe, gradually spreading further north and south. The

Krakatoa (or Krakatau)[1] erupted with a force more than ten thousand times that of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima (Thornton 1). The world quickly took notice. Officials reported the eruption via undersea telegraph cables. People thousands of miles away heard the explosion, and instruments around the world recorded changes in air pressure and sea level. In the months that followed, newspapers and journals printed vivid accounts of spectacular sunsets caused by fine particles that the volcano spewed into the upper atmosphere and that circled the globe, gradually spreading further north and south. The ![]() Royal Society, a British academy of scientists, formed a special Krakatoa committee to collect these articles, other eye-witness testimony, and more precise data (such as barograph readings of air pressure) to analyze the material meticulously and to publish a thorough report of their findings. Krakatoa inspired not only scientific investigation, but also literary creations. Gerard Manley Hopkins published a letter describing the Krakatoa sunsets in evocative and figurative language. Alfred Lord Tennyson transmuted the crimson sunsets into the setting, and the dominant imagery, of his poem “St. Telemachus.” In Blown to Bits, R. M. Ballantyne interwove a detailed, factual account of Krakatoa’s destruction with an invented tale of exploration, revenge, and romance, centered on fictional characters who narrowly escape the eruption and tsunamis. M. P. Shiel used a volcanic eruption as the major plot device in his last man novel, The Purple Cloud, and, in his depiction of a fictional eruption, Shiel mimicked the central place of the telegraph and the periodical press for scientists’ and laymen’s knowledge of Krakatoa.

Royal Society, a British academy of scientists, formed a special Krakatoa committee to collect these articles, other eye-witness testimony, and more precise data (such as barograph readings of air pressure) to analyze the material meticulously and to publish a thorough report of their findings. Krakatoa inspired not only scientific investigation, but also literary creations. Gerard Manley Hopkins published a letter describing the Krakatoa sunsets in evocative and figurative language. Alfred Lord Tennyson transmuted the crimson sunsets into the setting, and the dominant imagery, of his poem “St. Telemachus.” In Blown to Bits, R. M. Ballantyne interwove a detailed, factual account of Krakatoa’s destruction with an invented tale of exploration, revenge, and romance, centered on fictional characters who narrowly escape the eruption and tsunamis. M. P. Shiel used a volcanic eruption as the major plot device in his last man novel, The Purple Cloud, and, in his depiction of a fictional eruption, Shiel mimicked the central place of the telegraph and the periodical press for scientists’ and laymen’s knowledge of Krakatoa.

The August 1883 eruption was not entirely unexpected, but nearly so. Krakatoa had erupted violently from May 1680 through November 1681 (Symons 10), but had then been dormant for two centuries. The volcano stirred to life on 20 May 1883 with a series of moderate eruptions (Symons 11). Locals took note but were not especially alarmed. In fact, the island briefly became a tourist attraction. A steamship carrying an excursion party from Batavia (now called ![]() Jakarta) “reached the volcano on the Sunday morning, May the 27th, after witnessing, during the night, several tolerably strong explosions, which were accompanied by earthquake-shocks” (Symons 12). These visitors may have been foolhardy, but some were quite observant, and later were able to provide valuable data, such as estimates of the size of the crater, the frequency of explosions, and the height of the vapor column. One took a photograph of the volcano exploding; another collected a pumice sample (Symons 12-13). Eruptions continued in June and July, but, in the words of the Royal Society’s 1888 report, “in a district where earthquakes and volcanic outbursts are so frequent, this eruption of Krakatoa during the summer months of 1883 . . . soon ceased to attract any particular attention” (Symons 13).

Jakarta) “reached the volcano on the Sunday morning, May the 27th, after witnessing, during the night, several tolerably strong explosions, which were accompanied by earthquake-shocks” (Symons 12). These visitors may have been foolhardy, but some were quite observant, and later were able to provide valuable data, such as estimates of the size of the crater, the frequency of explosions, and the height of the vapor column. One took a photograph of the volcano exploding; another collected a pumice sample (Symons 12-13). Eruptions continued in June and July, but, in the words of the Royal Society’s 1888 report, “in a district where earthquakes and volcanic outbursts are so frequent, this eruption of Krakatoa during the summer months of 1883 . . . soon ceased to attract any particular attention” (Symons 13).

Residents of the ![]() Javan and

Javan and ![]() Sumatran coasts near Krakatoa quickly became alarmed on 26 August 1883 when more serious explosions began, some accompanied by tsunamis (Thornton 11-12). The next morning the situation became much more dire. Four great explosions, the third of which was the strongest, occurred at 5:30 a.m., 6:44 a.m., 10:02 a.m., and 10:52a.m. Krakatoa time (Symons 22).[2] Two-thirds of the island of Krakatoa disappeared (Symons 23), likely by collapsing into the hollow cavity left by the eruption of pumice (Simkin and Fiske 18). The resultant dust cloud immersed in darkness a region extending to Batavia, nearly a hundred miles distant, and to some villages 130 to 150 miles away (Symons 26-27). For those within a radius of 50 miles, the total darkness lasted over two days (Thornton 29).[3]

Sumatran coasts near Krakatoa quickly became alarmed on 26 August 1883 when more serious explosions began, some accompanied by tsunamis (Thornton 11-12). The next morning the situation became much more dire. Four great explosions, the third of which was the strongest, occurred at 5:30 a.m., 6:44 a.m., 10:02 a.m., and 10:52a.m. Krakatoa time (Symons 22).[2] Two-thirds of the island of Krakatoa disappeared (Symons 23), likely by collapsing into the hollow cavity left by the eruption of pumice (Simkin and Fiske 18). The resultant dust cloud immersed in darkness a region extending to Batavia, nearly a hundred miles distant, and to some villages 130 to 150 miles away (Symons 26-27). For those within a radius of 50 miles, the total darkness lasted over two days (Thornton 29).[3]

The greatest destruction was caused not by ash and fire but by water. The most violent of the explosions, occurring at approximately 10:02 a.m. on 27 August 1883, triggered an immense tsunami. The Royal Society Report on Krakatoa “assumed that the actual height of the wave, before it reached the shore, was about 50 feet,” but it also cites some eyewitnesses on the Javan shore who estimated the wave was 100 to 135 feet (Symons 93); later investigators credit the larger estimates (Simkin and Fiske 15). Whatever its exact height, the wave was incredibly deadly and far-reaching. Officially, it killed 36,417 inhabitants of coastal towns and villages, though more may have died (Thornton 13; Simkin and Fiske 15), and its faint remnants were detected as far away as ![]() the English Channel (Thornton 18). The 10:02 a.m. explosion also produced the furthest-travelling audible sound in recorded history (Thornton 1); it was heard over almost one-thirteenth of the earth’s surface, including at

the English Channel (Thornton 18). The 10:02 a.m. explosion also produced the furthest-travelling audible sound in recorded history (Thornton 1); it was heard over almost one-thirteenth of the earth’s surface, including at ![]() Rodrigues Island approximately 3,000 miles across the Indian Ocean from Krakatoa (Symons 79).

Rodrigues Island approximately 3,000 miles across the Indian Ocean from Krakatoa (Symons 79).

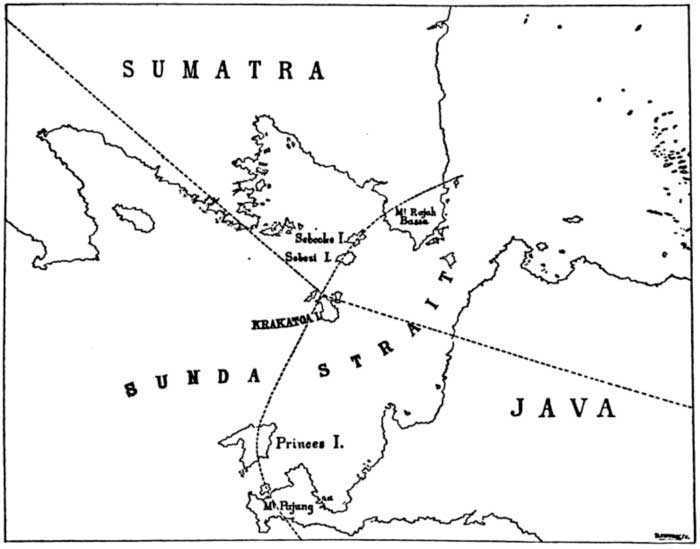

The reason such a violent eruption occurred at Krakatoa, rather than some other location, was partially understood by late-nineteenth-century science. According to the Royal Society’s 1888 Report on Krakatoa’s eruption, “The marked linear arrangement in this immense chain of volcanic mountains [across Java and Sumatra] points to the existence of a great fissure in the earth’s crust, along which the subterranean energy has been manifested” (Symons 4). At the ![]() Strait of Sunda, a second fissure crosses it almost at a right angle (Symons 4), and Krakatoa lies “at the point of intersection of these two great lines of volcanic fissure” (Symons 5; see Fig. 1).

Strait of Sunda, a second fissure crosses it almost at a right angle (Symons 4), and Krakatoa lies “at the point of intersection of these two great lines of volcanic fissure” (Symons 5; see Fig. 1).

Royal Society

Map” title=”1RoyalSocietyMap” width=”700″ height=”549″ class=”size-full wp-image-1981″ /> Figure 1: Map from the Royal Society Report, labeled “Sketch-map of the Sunda Strait, showing the lines of volcanic fissure which appear to traverse the district” (Symons 4)Modern geology affirms this general idea, but offers a more specific explanation for the convergence of volcanic activity. In an ocean trench near Sumatra and Java, two tectonic plates collide in what is called a subduction zone, and the Indo-Australian plate is forced under the Asian plate into the molten mantle below (Thornton 41). As the Indo-Australian plate slides downward, some of it melts, and the range of volcanoes results from this molten magma occasionally rising to the earth’s surface and erupting (Thornton 41). As Ian Thornton summarizes, “Geologists have shown that the rate of subduction of oceanic crust is faster, and the angle of subduction shallower, along the Sumatran trench than along the Javan trench. The change is abrupt and occurs at Sunda Strait” (43), the fulcrum around which Sumatra has slowly rotated twenty degrees clockwise in relation to Java over the past two million years (Thornton 42-43).

Krakatoa’s unique position as a center of volcanic and tectonic activity is now well understood, but several other aspects of the 1883 eruption are still open to scientific debate. Explanations for the cause of the third great explosion and the accompanying tsunami generally fall into two competing camps, with some arguing for an upward explosion as seawater reacted with hot magma, and others for the downward collapse of the volcano’s walls. Simkin and Fiske consider the debate settled: “Verbeek, the Dutch Mining engineer studying Krakatau immediately after the eruption, correctly deduced that the missing portion of the island had collapsed into the circular void left by the eruption of huge volumes of pumice. Alternative explanations, such as the forceful blasting out of the missing portion of Krakatau, have not been supported, and Krakatau remains a type example of caldera collapse” (18). Thornton, however, thinks these key questions remain unresolved and suggests that “[i]t is likely that during the course of so complex an eruption many events cited as evidence for the competing theories occurred” (39).

Scientists also continue to scrutinize Krakatoa as a case study in the formation and development of an island ecosystem. Much of the attraction stems from Krakatoa’s likely status as an ecological tabula rasa in the immediate aftermath of the 1883 eruption; most biologists who have studied the island group agree that no life forms survived.[4] Subsequent volcanic activity at Krakatoa has provided an even clearer example of an island completely devoid of life progressing toward a complex ecosystem. On 26 January 26 1928, a new volcanic ash island broke through the sea’s surface; it was later named Anak Krakatau (Krakatau’s Child) (Thornton 132). The new island was destroyed by sea erosion three times, but in August 1929 a fourth version of the island arose and became a permanent fixture in the Krakatoa island group (Thornton 133). The emerging ecosystems on both the remnants of the old Krakatoa islands and on Anak Krakatau could provide guidance for reconstructing ecosystems that have been devastated by human activity, such as logging and mining (Thornton 251). As Thornton explains, the rules by which different species arrive and interact in a new ecosystem “appear to depend strongly on the historical context” (262), and Krakatoa offers an unusually thorough historical record for current scientists because of the sustained and systematic attention it has received since 1883.

Such attention, from scientists and laymen around the globe, began within hours of the eruption, because news of it travelled rapidly via the worldwide network of telegraph lines. “The instantaneity of the telegraph reports,” Richard Hamblyn argues, “create[ed] an entirely new category of disaster: the universal news event, a story followed, in the case of Krakatau, by more than half the world’s population” (179). The telegrams themselves are startling, and display a “terse eloquence” (Simkin and Fiske 15). A telegram sent from Batavia to ![]() Singapore on 27 August 1883 reads:

Singapore on 27 August 1883 reads:

Noon. —Serang in total darkness all morning—stones falling. Village near Anjer washed away.

Batavia now almost quite dark—gas lights extinguished during the night—unable communicate with Anjer—fear calamity there—several bridges destroyed, river having overflowed through rush sea inland. (qtd. in Simkin and Fiske 14)

Calamity had, indeed, struck Anjer: at approximately 9:00 that morning, a large wave had inundated the coastal town (Simkin and Fiske 38). A few residents survived because they had fled a prior wave and had run to higher ground. Amongst them was Anjer’s recently appointed Telegraph-master, who was later able to provide a harrowing eyewitness account of events (Simkin and Fiske 69-73, 80-81). Despite, or perhaps because of, the horrifying nature of the eruption, some of the telegrams from Batavia are almost poetic in their condensed eloquence and evocative figurative language. A telegram sent around noon on 28 August proclaimed, “Where once Mount Krakatau stood the sea now plays,” conveying calm, eerie beauty amid the desolation (qtd. in Simkin and Fiske 14).

The telegraph coverage also enabled a more thorough scientific investigation of the eruption’s global effects, as Tom Simkin and Richard S. Fiske stress in their magisterial centennial review of Krakatoa:

Telegrams bearing news of the Krakatau eruption spread quickly and accounts soon appeared in newspapers around the world. . . . Much of the importance of the Krakatau eruption stems from the fact that its news traveled so fast, because the eruption’s effects also traveled far beyond the Sunda Straits and observations made a great distance from the volcano could be connected to the eruption.[5] (15)

Because the global scope of both Krakatoa’s effects and the news of its eruption quickly reached many interested observers, “for the first time, discrete local observations . . . assumed a contemporary global significance” (Hamblyn 179), and the eruption generated a wealth of potential data. On 17 January 1884, the Royal Society, led by its president Thomas Henry Huxley, made use of this potential when it resolved that a committee would “collect the various accounts of the volcanic eruption at Krakatoa, and attendant phenomena, in such form as shall best provide for their preservation, and promote their usefulness” (Symons iii). (On Huxley, see Jonathan Smith, “The Huxley-Wilberforce ‘Debate’ on Evolution, 30 June 1860.″) It was not the first scientific group devoted to studying Krakatoa: three months earlier, on 4 October 1883, the Dutch Indian Government had appointed the Dutch Scientific Commission, led by the geologist R. D. M. Verbeek, to study the eruption. Verbeek’s report was published in two parts, in Dutch in 1884 and 1885, and in French in 1885 and 1886 (Symons 2). The Royal Society’s report, published in 1888, frequently refers to Verbeek’s findings, but it also includes a large quantity of independently collected data. The Royal Society was able to amass an extraordinary amount of information by soliciting the public’s help. The committee placed an advertisement in the London Times in February 1884 asking for “authenticated facts” and published papers concerning drifts of pumice, changes in barometric pressure and sea level, locations where explosions were heard, and unusual optical effects in the atmosphere (Symons iv). After it received numerous accounts from scientists and amateur observers, the multidisciplinary committee spent 28 months analyzing the data and writing the report, which was edited by G. J. Symons, the committee’s chair (Symons vi).

The Times ad requested that “[c]orrespondents . . . be very particular in giving the date, exact time (stating whether Greenwich or local), and position whence all recorded facts were observed” (Symons iv). Such specificity was essential for calculating the distances and velocities of the oceanic and atmospheric phenomena associated with the eruption. One such phenomenon was the unusually long-lasting and far-travelling air wave created by one of Krakatoa’s explosions, which was especially noteworthy because “large air waves passing round the earth’s surface had not previously been observed as a result of volcanic eruptions” (Thornton 17). The air wave expanded outward from Krakatoa until it formed a circle around the earth’s circumference, then it contracted to a point on the globe directly opposite Krakatoa (a point which happens to lie near ![]() Bogotá, Colombia [Thornton 17]). The air wave then continued away from Bogotá and back toward Krakatoa, and the process repeated. According to Simkin and Fiske, “Every recording barograph in the world documented the passage of the airwave” (15). Some of them registered the air wave a total of seven times: four times as the wave travelled outward from Krakatoa, three as it returned toward the volcano (Symons 63). The committee used the precise times and locations of the barogram readings to calculate the speed of the air waves, which ranged from 674 to 726 miles per hour, “very nearly the characteristic velocity of sound” (Symons 72).

Bogotá, Colombia [Thornton 17]). The air wave then continued away from Bogotá and back toward Krakatoa, and the process repeated. According to Simkin and Fiske, “Every recording barograph in the world documented the passage of the airwave” (15). Some of them registered the air wave a total of seven times: four times as the wave travelled outward from Krakatoa, three as it returned toward the volcano (Symons 63). The committee used the precise times and locations of the barogram readings to calculate the speed of the air waves, which ranged from 674 to 726 miles per hour, “very nearly the characteristic velocity of sound” (Symons 72).

The committee also discussed the speed at which fine ash and dust travelled through the upper atmosphere. Scientists inferred the presence of microscopic particles from the unusual atmospheric effects they produced, which included intense and long-lasting sunsets, a blue or green tinge to the sun and moon, and a large, corona-like haze around the sun. Reverend Sereno E. Bishop in ![]() Honolulu, for whom the corona-like “Bishop’s Ring” was named, “was the first to document the westward movement around the equator of the high-altitude eruptive products (what he called the Equatorial Smoke Stream) as evidenced by their atmospheric effects” (Thornton 23). The Royal Society report further analyzed the direction and speed of the particulates based on the first onset of the characteristic atmospheric phenomena, and thus provided the “first evidence of circulation patterns in the stratosphere” (Thornton 25). The Krakatoa committee discovered that the equatorial smoke stream made a complete circuit around the globe several times, each time taking about thirteen days (Symons 322), “mov[ing] at about 73 miles an hour from east to west, and gradually spread[ing] southwards and northwards” (Symons 325). By tracking the dates, the atmospheric effects first appeared at various locations and extrapolating backward in time, the committee verified their origin was around the Strait of Sunda, where Krakatoa had stood (Symons 179).

Honolulu, for whom the corona-like “Bishop’s Ring” was named, “was the first to document the westward movement around the equator of the high-altitude eruptive products (what he called the Equatorial Smoke Stream) as evidenced by their atmospheric effects” (Thornton 23). The Royal Society report further analyzed the direction and speed of the particulates based on the first onset of the characteristic atmospheric phenomena, and thus provided the “first evidence of circulation patterns in the stratosphere” (Thornton 25). The Krakatoa committee discovered that the equatorial smoke stream made a complete circuit around the globe several times, each time taking about thirteen days (Symons 322), “mov[ing] at about 73 miles an hour from east to west, and gradually spread[ing] southwards and northwards” (Symons 325). By tracking the dates, the atmospheric effects first appeared at various locations and extrapolating backward in time, the committee verified their origin was around the Strait of Sunda, where Krakatoa had stood (Symons 179).

Some of the descriptions are remarkably precise about not only the date and geographical location where a sunset afterglow was first observed, but also about the timing and location in the sky of its particular colors. F. A. Rollo Russell, who compiled the Royal Society Report’s section on the unusual twilight glows, included his own description of the 11 December 1883 sunset in ![]() Surrey:

Surrey:

At 4.15 green spot about 10° above the horizon. Pink up to and beyond zenith, and on both sides . . . . Whole sky at 4.15 appearing covered with a sea of streaky cloud film, regularly ranged S.S.W. to N.N.E.; no appearance of a radiant point. At 4.20 spot of green being closed in by bright pink all over western sky . . . . At 4.30 pink edge about 22° from horizon. Green sunk beyond horizon. At 4.36 pink, about 15°. Sky blue. At 4.41 edge of red glow about 10° above horizon. (Symons 164)

Such precision about the order and duration of the sunset colors allowed the committee to hypothesize the composition of the stratospheric particles from Krakatoa: “small reflecting dust, partially transparent and partially opaque, or else . . . a mixture of transparent spherules and fragments” (Symons 186). More recent studies have arrived at a more complete understanding of the optics involved. H. H. Lamb, writing in 1970, explains the interaction of particles of different diameters with light of different wavelengths (and hence different colors). Lamb argues that volcanic dust smaller than ½ micrometer (½ µm = 1/51,000 inch) produces especially red suns, while blue suns and moons are produced by larger particles of 1 to 5 µm, and the Bishop’s rings seen after Krakatoa resulted from many particles in the narrow size range of 0.8 to 1 µm (qtd. in Simkin and Fiske 404-05). Since larger dust particles fall out of the atmosphere more quickly and do not spread as far, “the bigger the particles the rarer, more localized and short-lived the occurrence” (Lamb, qtd. In Simkin and Fiske 407); hence the large temporal and geographical range of the lurid red sunsets, and more limited range of the blue and green suns.

The widespread sunset effects attracted the attention of many observers, and the Royal Society Report quotes extensively from accounts of the sunsets previously published in the periodical press. One such account is the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins’s letter in the 3 January 1884 edition of Nature. The Royal Society Report offers this summary:

Mr. Gerard Hopkins of Stonyhurst College, notes the following difference between ordinary sunsets and the displays of 1883:—

‘(1). They differ in their time and in the place of the sky where they appear.

‘(2). They differ in their periodic action or behaviour.

‘(3). They differ in the nature of the glow, which is both intense and lustreless.

‘(4). They differ in the regularity of their colouring. Four colours in particular have been noticeable, orange lowest and nearest the sundown; above this and broader, green; above this, and broader still, a variable red, ending in being crimson; above this, a faint lilac. The lilac disappears, the green deepens, spreads, and encroaches on the orange, and the red deepens, spreads, and encroaches on the green, till at last one red, varying downwards from crimson to scarlet or orange, fills the west and south.

‘(5). They differ in the colours themselves, which are impure and not of the spectrum.

‘(6). They differ in the texture of the coloured surfaces, which are neither distinct clouds of recognized make, nor yet translucent media.’

The above is merely an abstract of Mr. Hopkins’s letter, to which he subjoins a very lucid description of the sunset of December 16, 1883. (Symons 172)

For the most part, the Report’s authors directly quote Hopkins, though they paraphrase points one and six. The remarkable aspect of their précis, however, is what it leaves out—extensive sections of evocative, metaphoric description. Hopkins describes the evening as follows:

After the sunset the horizon was, by 4.10, lined a long way by a glowing tawny light, not very pure in colour and distinctly textured in hummocks, bodies like a shoal of dolphins, or in what are called gadroons, or as the Japanese conventionally represent waves. The glowing vapour above this was as yet colourless; then this took a beautiful olive or celadon green, not so vivid as the previous day’s, and delicately fluted; the green belt was broader than the orange, and pressed down on and contracted it. Above the green in turn appeared a red glow, broader and burlier in make; it was softly brindled, and in the ribs or bars the colour was rosier, in the channels where the blue of the sky shone through it was a mallow colour. Above this was a vague lilac. (“Remarkable Sunsets” 223)

Hopkins’s poetic language has its own descriptive precision. As Thomas A. Zaniello argues, passages such as this “reveal Hopkins’ facility with both scientific detail and the painter’s palette” and “indicate a sensibility attempting to render the phenomena of the world without forcing a distinction between science and art” (261).[6] Indeed, to describe the texture of the “tawny light,” Hopkins first turns to nature (a metaphor drawn from a landscape and a simile from sea life) and then turns to art (both Western decorative carving and Eastern painting).

The letter also incorporates imagery and diction from some of the poems for which Hopkins is now best known. The “softly brindled” red glow evokes the opening of his 1877 poem “Pied Beauty,” which uses the more archaic form “brinded” to describe a streaked or flecked sky: “Glory be to God for dappled things— / For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow” (1-2). Consider, too, the language in Hopkins’s explanation of how normal, bright sunsets differ from the lusterless Krakatoa afterglows:

A bright sunset lines the clouds so that their brims look like gold, brass, bronze, or steel. It fetches out those dazzling flecks and spangles which people call fish-scales. It gives to a mackerel or dappled cloudrack the appearance of quilted crimson silk, or a ploughed field glazed with crimson ice. These effects may have been seen in the late sunsets, but they are not the specific after-glow; that is, without gloss or lustre. (“Remarkable Sunsets” 222-23)

The description of this streaked sky echoes both “Pied Beauty” and “The Windhover.” The letter’s use of “dappled” brings to mind the former poem’s praise of “dappled things” (1), and the latter poem’s description of the titular bird as a “dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon” (2). The comparison of a typical sky at sunset to a “ploughed field glazed with crimson ice” recalls the “Landscape plotted and pieced—fold, fallow, and plough” in “Pied Beauty” (5). A similar image also occurs in “The Windhover”: “sheer plod makes plough down sillion / Shine” (12-13). Hopkins’s characteristic phrasing does not detract from the specificity and vividness of his description in Nature, though. Patricia Ball rightly claims that the letter uses “turns of phrase or analogy and a choice of words which are characteristic of him,” but they “serve the purpose to which the whole correspondence is directed, the accurate plotting of remarkable skyscapes” (116).

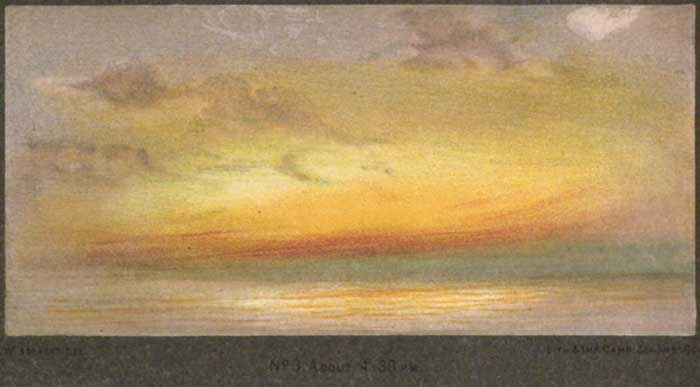

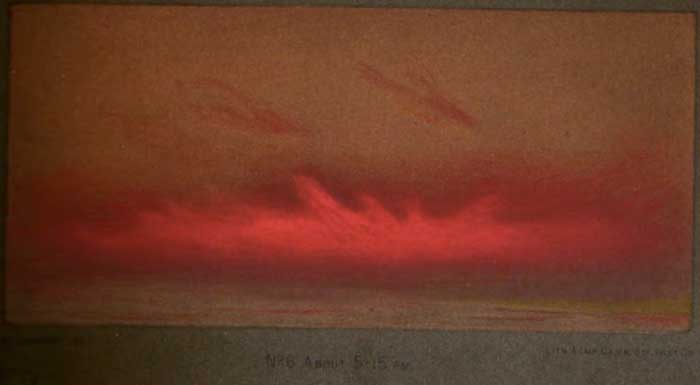

Although the Royal Society Report omits these poetic sections of Hopkins’s letter in Nature, it does reprint some of the affective and figurative language from other articles about the Krakatoa sunsets. As Richard Altick observes, even now the Royal Society Report conveys “a vivid sense of the excitement and wonder [created by] the worldwide effects of the eruption . . . . [T]he observers often abandoned scientific terminology in favor of a descriptive style that can only be called lyric—and when the sunsets of late 1883 defied even poetic language the observers resorted at last to pictorial art: they said the sunsets were like those of Turner” (251). Altick may have had in mind E. L. Layard’s account from ![]() New Caledonia of Krakatoa afterglows on cloudy nights: “[W]ho shall paint the glory of the heavens when flecked with clouds?— burnished gold, copper, brass, silver, such as Turner in his wildest dreams never saw, and of such fantastic forms!” (Symons 173). Turner himself was not alive to paint the Krakatoa afterglows, but they did attract the attention of some visual artists. Frederic Edwin Church’s “Sunset over the Ice of Chaumont Bay, Lake Ontario,” a watercolor painted on 28 December 1883, is “the only major painting to be created in the immediate aftermath of Krakatoa” (Winchester 281). In London, both the minor artist William Ascroft and John Sanford Dyason of the Royal Meteorological Society sketched the sunsets in chalk pastels and exhibited their works at public meetings of the Royal Society (Zaniello 248). The frontispiece to the Royal Society’s Krakatoa Report reproduces six of Ascroft’s sketches “made on the bank of the

New Caledonia of Krakatoa afterglows on cloudy nights: “[W]ho shall paint the glory of the heavens when flecked with clouds?— burnished gold, copper, brass, silver, such as Turner in his wildest dreams never saw, and of such fantastic forms!” (Symons 173). Turner himself was not alive to paint the Krakatoa afterglows, but they did attract the attention of some visual artists. Frederic Edwin Church’s “Sunset over the Ice of Chaumont Bay, Lake Ontario,” a watercolor painted on 28 December 1883, is “the only major painting to be created in the immediate aftermath of Krakatoa” (Winchester 281). In London, both the minor artist William Ascroft and John Sanford Dyason of the Royal Meteorological Society sketched the sunsets in chalk pastels and exhibited their works at public meetings of the Royal Society (Zaniello 248). The frontispiece to the Royal Society’s Krakatoa Report reproduces six of Ascroft’s sketches “made on the bank of the ![]() Thames, a little west of London, on the evening of November 26th, 1883,” which “represent the general colouring of the western sky from shortly after sunset (3h. 57m. p.m.) to the final dying out of the after-glow at about 5.15 p.m.” (Symons n.pag.). Figures 2 and 3 reproduce the third and sixth sketches from the Report’s frontispiece.

Thames, a little west of London, on the evening of November 26th, 1883,” which “represent the general colouring of the western sky from shortly after sunset (3h. 57m. p.m.) to the final dying out of the after-glow at about 5.15 p.m.” (Symons n.pag.). Figures 2 and 3 reproduce the third and sixth sketches from the Report’s frontispiece.

Figure 2: Sketch by William Ascroft of Krakatoa afterglow as seen in London at 4:30p.m. on 26 November 1883, from the frontispiece to the Royal Society Report

Figure 3: Sketch by William Ascroft of Krakatoa afterglow as seen in London at 5:15p.m. on 26 November 1883, from the frontispiece to the Royal Society Report

Earlier in E. L. Layard’s description of the sunset on 6 January 1884, he uses what was arguably the most common simile in all the verbal descriptions of Krakatoa afterglows: “about 8 p.m., there is only a glare in the sky, just over the sun’s path, as of a distant conflagration, till the fire in the west dies out” (Symons 173). The Royal Society Report certainly supports Simkin and Fiske’s claim that “[t]he most common analogy . . . was fire, and the word ‘conflagration’ was repeatedly used” (157). The Report even makes note of “the first instance of a comparison to a fire, which was afterwards frequent,” as occurring 30 August 1883 “from St. Helena, 16˚S. 6˚W., where at 4 a.m. on the 30th a red light in the south-east and south-west, ‘like a fire,’ alarmed one of the inhabitants” (Symons 316). Though it was originally published somewhat later, in September 1883, another quoted description has the distinction of appearing first among those reprinted in the Royal Society Report, and it, too, compares the afterglows to an immense fire. The Reverend Sereno E. Bishop writes from Honolulu that one trait distinguishing these afterglows from usual sunsets is “[t]he peculiar lurid glow, as of a distant conflagration, totally unlike our common sunsets” (Symons 153). In some cases, observers actually mistook the glows for distant fires and brought in local fire brigades, as happened on 27 November 1883 in New York and ![]() Connecticut (Thornton 24).

Connecticut (Thornton 24).

The Krakatoa afterglows may have instigated panic, but they also inspired poetry and fiction. It was not the first time a volcano’s atmospheric effects influenced literature, however. The June 1783 eruption of ![]() Laki in

Laki in ![]() Iceland released massive amounts of sulfur dioxide, which produced noxious fogs, an unusually red sun, and an extremely hot summer followed by an extremely cold winter, conditions which influenced William Cowper’s depiction of time and weather in The Task (Menely 480-89; Hamblyn 101-102).

Iceland released massive amounts of sulfur dioxide, which produced noxious fogs, an unusually red sun, and an extremely hot summer followed by an extremely cold winter, conditions which influenced William Cowper’s depiction of time and weather in The Task (Menely 480-89; Hamblyn 101-102). ![]() The gas and dust spewed into the atmosphere by the April 1815 eruption of Tambora in

The gas and dust spewed into the atmosphere by the April 1815 eruption of Tambora in ![]() Indonesia disrupted usual rainfall patterns, cooled global temperatures, caused famines and epidemics, and instigated political upheavals, conditions which in turn inspired Mary Shelley’s desolate novel Frankenstein and Lord Byron’s apocalyptic poem “Darkness” (Wood). (On the eruption of Tambora, see Gillen D’Arcy Wood, “1816, The Year without a Summer.”)

Indonesia disrupted usual rainfall patterns, cooled global temperatures, caused famines and epidemics, and instigated political upheavals, conditions which in turn inspired Mary Shelley’s desolate novel Frankenstein and Lord Byron’s apocalyptic poem “Darkness” (Wood). (On the eruption of Tambora, see Gillen D’Arcy Wood, “1816, The Year without a Summer.”)

Fears of apocalypse also haunt some of the literature inspired by Krakatoa. Altick has gathered and compared writings by four Victorian poets that incorporate descriptions of the Krakatoa sunsets, including poems by Robert Bridges, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and Alfred Tennyson, and Hopkins’s letter in Nature. The most cheerful of them is the “March” section of Robert Bridges’s Eros and Psyche (1885), which includes a three-stanza description of a sunset, the second stanza of which reads:

Broad and low down, where late the sun had been

A wealth of orange-gold was thickly shed,

Fading above into a field of green,

Like apples ere they ripen into red,

Then to the height a variable hue

Of rose and pink and crimson freak’d with blue,

And olive-border’d clouds o’er lilac led. (st. 25)

Altick suspects the passage is derivative of Hopkins’s letter in Nature; he notes the almost identical color terminology, and quotes a letter from Hopkins to Bridges in which Hopkins politely comments on the similarity and inquires if Bridges read his Nature piece (256).

Swinburne’s “A New-Year Ode: to Victor Hugo” repeatedly uses images of sunset and sunrise, clouds and storms, and fire to represent both the eras Hugo depicted, and the one through which he lived. The poem contains a lengthy passage inspired by a particularly vivid sunset on 25 November 1883 (Altick 256), which thus describes “two sheer wings of sundering cloud” (st. 17) above the set sun:

As midnight black, as twilight brown, they spread,

But feathered thick with flame that streaked and lined

Their living darkness, ominous else of dread,

From south to northmost verge of heaven inclined

Most like some giant angel’s, whose bent head

Bowed earthward, as with message for mankind

Of doom or benediction to be shed

From passage of his presence. Far behind,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Heaven, manifest in manifold

Light of pure pallid amber, cheered with fire of gold. (st. 18)

The detailed description of the sunset continues, and leads into a comparison of the sunset glow to “light like fire of love” (st. 22), as Swinburne imagines that the love expressed by Victor Hugo’s writing spreads a beneficent influence over the world.[7]

Flame also figures prominently in “St. Telemachus” (1892), a poem by Tennyson whose opening lines were, according to Tennyson’s note, “[s]uggested by the memory of the eruption of Krakatoa”:

Had the fierce ashes of some fiery peak

Been hurled so high they ranged about the globe?

For day by day, through many a blood-red eve,

In that four-hundredth summer after Christ,

The wrathful sunset glared against a cross

Reared on the tumbled ruins of an old fane

No longer sacred to the Sun, and flamed

On one huge slope beyond. . . (1-8)

The poem tells the story of the hermit Telemachus’s divine inspiration to walk to the ![]() Roman Colosseum where he attempts to stop the gladiatorial combat. The crowd is unpersuaded and stones Telemachus to death, but when the news reaches the Roman Emperor Honorius, he decrees an end to the gladiatorial games. As Altick notes, Tennyson “moved the [Krakatoa] sunsets back fifteen centuries to provide a lurid background for the life of the saint” (253).

Roman Colosseum where he attempts to stop the gladiatorial combat. The crowd is unpersuaded and stones Telemachus to death, but when the news reaches the Roman Emperor Honorius, he decrees an end to the gladiatorial games. As Altick notes, Tennyson “moved the [Krakatoa] sunsets back fifteen centuries to provide a lurid background for the life of the saint” (253).

If the Krakatoa sunsets struck some observers as “almost apocalyptic, often unnerving” (Winchester 290), then Tennyson’s portrayal of the sunsets as “blood-red” and “wrathful” captures their unnerving quality (3, 5), and his transposition of the sunsets to Telemachus’s “deed that woke the world” (70) associates them with the transition to a new epoch in history (from polytheism to Christianity). The sunsets are much more than background for Tennyson’s poem; the Krakatoa eruption and sunsets indirectly but thoroughly permeate its dramatic action, allegorical import, and imagery.[8] Tennyson imagines that St. Telemachus, in the evenings when the fane was

Bathed in that lurid crimson—asked ‘Is earth

On fire to the West? or is the Demon-god

Wroth at his fall?’ . . . (18-20)

His questions juxtapose a common reaction to the Krakatoa sunsets (mistaking them for a distant conflagration) with Tennyson’s thematic use for them (the transition from paganism to Christianity). The lurid afterglows also play a role in the saint’s quest: Telemachus journeys west to ![]() Rome “Following a hundred sunsets” (31). Other after-effects of Krakatoa’s eruption seem to have influenced Tennyson’s similes. When Telemachus arrives in Rome, he comes upon a crowd:

Rome “Following a hundred sunsets” (31). Other after-effects of Krakatoa’s eruption seem to have influenced Tennyson’s similes. When Telemachus arrives in Rome, he comes upon a crowd:

And borne along by that full stream of men,

Like some old wreck on some indrawing sea,

Gained their huge Colosseum. . . (43-45)

The image of rushing sea water bearing a ship inward accords with the Krakatoa-induced tsunamis, one of which carried a ship two miles inland (Thornton 13).[9] Tennyson’s description of Telemachus’s death at the hands of the Colosseum crowd— “Then one deep roar as of a breaking sea, / And then a shower of stones that stoned him dead” (67-68)—literally depicts the saint’s death by stoning but also evokes the sound of a tsunami and the hail of pumice unleashed by Krakatoa’s eruption.

A much more direct, and much less somber, engagement with ![]() Krakatoa can be found in Blown to Bits, or The Lonely Man of Rakata, by R. M. Ballantyne. This 1889 adventure novel for boys shares many of the characteristics of a group of earlier, Pompeii-inspired eruption narratives recently discussed by Nicholas Daly. In late-eighteenth- and early-nineteeenth-century disaster narratives, “the volcano is there as a smoldering presence from the start, and our pleasure in other elements of our experience is both shadowed and enhanced by our knowledge that in the end it will explode” (Daly 257). The very title of Ballantyne’s work directs his readers towards the novel’s explosive culmination, and the subtitle’s mention of

Krakatoa can be found in Blown to Bits, or The Lonely Man of Rakata, by R. M. Ballantyne. This 1889 adventure novel for boys shares many of the characteristics of a group of earlier, Pompeii-inspired eruption narratives recently discussed by Nicholas Daly. In late-eighteenth- and early-nineteeenth-century disaster narratives, “the volcano is there as a smoldering presence from the start, and our pleasure in other elements of our experience is both shadowed and enhanced by our knowledge that in the end it will explode” (Daly 257). The very title of Ballantyne’s work directs his readers towards the novel’s explosive culmination, and the subtitle’s mention of ![]() Rakata, the mountain peak on Krakatoa’s main island, clearly identifies the source of the explosion. Ballantyne’s ominous foreshadowing is frequent and strong. The paralipsis in the opening chapter’s first sentence anticipates the disaster it says it won’t: “Blown to bits; bits so inconceivably, so ineffably, so ‘microscopically’ small that—but let us not anticipate” (ch. 1; n. pag.). Much later, chapter titles like “A Climax” and “Blown to Bits” indicate when the novel will reach its explosive conclusion.

Rakata, the mountain peak on Krakatoa’s main island, clearly identifies the source of the explosion. Ballantyne’s ominous foreshadowing is frequent and strong. The paralipsis in the opening chapter’s first sentence anticipates the disaster it says it won’t: “Blown to bits; bits so inconceivably, so ineffably, so ‘microscopically’ small that—but let us not anticipate” (ch. 1; n. pag.). Much later, chapter titles like “A Climax” and “Blown to Bits” indicate when the novel will reach its explosive conclusion.

Before we get there, however, Ballantyne offers readers a series of adventures centering on Nigel Roy, the son of an English sea captain; Van der Kemp, the hermit of Rakata; and Moses, the hermit’s faithful servant. Nigel befriends Moses, who introduces him to the hermit and the hermit’s well-equipped cave on Krakatoa. The three embark on a journey to several nearby islands and always are greeted hospitably by the locals, since Van der Kemp, despite his nickname of hermit, has travelled extensively and made loyal friends seemingly everywhere. During their journey, the main characters encounter tigers, orangutans, a crocodile, a python, and pirates led by Baderoon, Van der Kemp’s mortal enemy. Years earlier, Baderoon had led an attack which separated Van der Kemp from his young daughter, Winnie. When Nigel hears the story, he suspects an orphan he met in the ![]() Cocos-Keeling Islands is Winnie, and he asks his father to transport Winnie to Anjer. Van der Kemp and his daughter are prematurely reunited when the hermit’s canoe is washed onto the deck of Captain Roy’s boat in the midst of Krakatoa’s catastrophic eruption. The tsunami generated by Krakatoa’s third and largest explosion propels the boat over the ruined city of Anjer and more than a mile inland, safely depositing the protagonists in a coconut grove.[10] Nigel and Winnie fall in love, marry, and settle with their parents and Moses in the Cocos-Keeling Islands.

Cocos-Keeling Islands is Winnie, and he asks his father to transport Winnie to Anjer. Van der Kemp and his daughter are prematurely reunited when the hermit’s canoe is washed onto the deck of Captain Roy’s boat in the midst of Krakatoa’s catastrophic eruption. The tsunami generated by Krakatoa’s third and largest explosion propels the boat over the ruined city of Anjer and more than a mile inland, safely depositing the protagonists in a coconut grove.[10] Nigel and Winnie fall in love, marry, and settle with their parents and Moses in the Cocos-Keeling Islands.

Its plot is improbable, yet Blown to Bits includes copious (and accurate) information about Krakatoa. As Joel D. Chaston remarks, “Ballantyne’s books are . . . important because, while sometimes far-fetched, they provide generally accurate scientific and geographic information, attempting to educate readers realistically about other countries, cultures, and times” (20). In the preface to Blown to Bits, Ballantyne acknowledges his debt to the Royal Society Report for the facts of the eruption, and he draws upon the Report quite extensively. The narrator sometimes directly quotes the Royal Society Report, as when he describes the moderate eruptions of May 1883 (Ballantyne ch. 8; Symons 11). More often, the narrator slightly paraphrases or summarizes the Report, as he does in the extensive discussion in Chapter 29 of Krakatoa’s global effects, including the sounds heard as far as Rodriguez, the air waves measured by barometers, the changes in sea level, the dust particles and their rate of travel, and the resultant atmospheric effects. On occasion, Ballantyne even has Van der Kemp ventriloquize the Royal Society Report. The hermit thus informs Nigel of Krakatoa’s dangerous position in a highly volcanic region:

The island of Java, with an area about equal to that of England, contains no fewer than forty-nine great volcanic mountains, some of which rise to 12,000 feet above the sea-level. Many of these mountains are at the present time active . . . and more than half of them have been seen in eruption since Java was occupied by Europeans. Hot springs, mud-volcanoes, and vapour-vents abound all over the island, whilst earthquakes are by no means uncommon. There is a distinct line in the chain of these mountains which seems to point to a great fissure in the earth’s crust, caused by the subterranean fires. This tremendous crack or fissure crosses the Straits of Sunda, and in consequence we find a number of these vents—as volcanic mountains may be styled—in the Island of Sumatra, which you saw to the nor’ard as you came along. But there is supposed to be another great crack in the earth’s crust—indicated by several volcanic mountains—which crosses the other fissure almost at right angles, and at the exact point where these two lines intersect stands this island of Krakatoa! (ch. 7; n. pag.)[11]

Clearly, as Van der Kemp educates Nigel about the region, so, too, does Ballantyne educate his young readers, in keeping with his stated intention “to bring the matter [of Krakatoa’s 1883 eruption], in the garb of a tale, before that portion of the juvenile world which accords me a hearing” (preface; n. pag.)

Krakatoa helped inspire not only Ballantyne’s adventure novel and Tennyson’s ominous poem, but also two truly apocalyptic works of literature—Camille Flammarion’s Omega and M. P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud. Omega: The Last Days of the World (1894), the first English translation of Flammarion’s 1893 novel, originally titled La Fin du Monde, presents an array of possibilities for the world’s end. In the twenty-fifth century, astronomers predict a comet composed partly of poisonous carbon monoxide will collide with the earth, and scientists speculate about numerous ways the comet might extinguish humanity. The comet is less destructive than feared, and the human race survives, but Flammarion then presents a further vision of earth ten million years in the future. Only two people remain alive amidst an entropic wasteland in which the earth’s elevations have eroded to a near-uniform surface, its water vapor has dissipated, and its surface temperature has dropped too low to sustain life. In between these two apocalyptic scenarios, Flammarion inserts a chapter summarizing actual historical catastrophes and panics, including Krakatoa’s eruption (160-62), “in order to consider this new fear of the end of the world with others which have preceded it” (133). Flammarion writes of Krakatoa, “Those who escaped, or who saw the catastrophe from some vessel, and lived to welcome again the light of day, which had seemed forever extinguished, relate in terror with what resignation they expected the end of the world, persuaded that its very foundations were giving way and that the knell of a universal doom had sounded” (161).

M. P. Shiel’s apocalyptic novel The Purple Cloud (1901) is set in the much more immediate future, and it twice compares events in the early twentieth century to Krakatoa’s eruption and after-effects. In the first instance, the narrator, Adam Jeffson, recounts:

[I]t was at sunset that my sense of the wondrously beautiful was roused and excited, in spite of that burden which I bore: for, certainly, I never saw sunsets . . . so flamboyant, exorbitant and distraught. . . . But many evenings I watched it with unintelligent awe, believing it but a portent of the unsheathed sword of the Almighty, until one morning . . . I suddenly remembered the wild sunsets of the nineteenth century witnessed in Europe, America, and, I think, everywhere, after the eruption of the volcano of Krakatoa. (77-78)

Adam has good reason to think the wild sunsets are a portent of apocalypse since the burden he bears is to live in the aftermath of a worldwide catastrophe. Having been the first man to reach the ![]() North Pole, Adam gradually realizes, as he returns home to England, that he is the last man left alive. A purple cloud of poisonous gas has enveloped nearly the entire planet, sparing only the very northernmost latitudes. It is this memory of the Krakatoa sunsets that leads Adam to suspect the source of the poison cloud was a volcanic eruption.

North Pole, Adam gradually realizes, as he returns home to England, that he is the last man left alive. A purple cloud of poisonous gas has enveloped nearly the entire planet, sparing only the very northernmost latitudes. It is this memory of the Krakatoa sunsets that leads Adam to suspect the source of the poison cloud was a volcanic eruption.

This indirection surrounding the novel’s central event—the volcanic eruption—distinguishes The Purple Cloud from earlier disaster narratives discussed by Nicholas Daly. In Shiel’s story, the volcano’s eruption is not the dramatic climax; instead, over eighty percent of the novel focuses on Adam’s survival after the disaster.[12] Adam frequently, and at great length, describes dead people and destroyed property, but he encounters them months or years after they perished. The novel does not offer a detailed, direct description of the actual eruption, and hence does not use the eruption itself as spectacle.

Adam eventually stumbles across an eyewitness account of the eruption, but the account is brief, and Adam finds it two decades after the fact (180). Albert Tissu, a passenger on board the ship the Marie Meyer (180), witnesses a volcanic island emerging from the sea and records the event in his journal: “we descry a shade rising, a shade, a mighty back, a new-born land, bearing skyward ten flames of fire, slowly, steadily, out of the sea” (181). Tissu hopes to be immortalized for documenting such an extraordinary event. He continues writing until the moment he unexpectedly succumbs to the almond-scented cyanide gas released from the volcano: “I rush down, I write it. . . . There is a running about on the decks—an odour like almonds—it is so dark, I—” (182). Shiel’s inclusion of a shipboard eyewitness is in keeping with the significance of sailors’ accounts for understanding Krakatoa. The Royal Society Report suggested, “Perhaps . . . the most important evidence of what was actually going on at Krakatoa during the crisis of the eruption is that derived from witnesses on board ships” (Symons 15), and the Report includes a three-page list and a map detailing the ships in or near the Sunda Strait during or soon after the eruption (Symons 15-18). Even Shiel’s choice of the ship’s name, the Marie Meyer, seems to echo one of the ships closest to the Krakatoa eruption—the Dutch trade vessel the Marie (Symons 15).

Tissu’s shipboard account is not the only example of The Purple Cloud mimicking the methods of representation through which witnesses reported and scientists studied the Krakatoa eruption. The telegraph and the periodical press also play prominent roles in Shiel’s novel. As Adam returns to Europe from the North Pole and searches for other survivors, he thinks of, but rejects, the telegraph and the wireless (the recently invented radio) as means of expediting his search: “I had some knowledge of the Morse code, of the manipulation of tape-machines, telegraphic typing-machines, wireless transmitting . . . so I could have wirelessed, or tried to wire from Bergen, to somewhere; but I would not: I was so afraid; afraid lest for ever from nowhere should occur one replying click, or stir of dial-needle” (78). Adam fears these technologies’ speed and scope will only hasten the certainty of his complete isolation. So horrifying is this prospect that he focuses on the absence of impersonal, mechanical clicks and dials rather than the absence of the urgent interpersonal communication they were meant to facilitate.

Adam has good reason to fear the telegraph’s silence. As he discovers through reading old newspapers, those yet unaffected by the cloud inferred its location and speed based on cessations of telegraph contact. One report in The Kent Express laments,

Communication with Tilsit,

Insterburg, Warsaw,

Cracow . . . and many smaller towns immediately east of the 21st of longitude has ceased during the night, though in some at least of them there must have been operators still at their posts, undrawn into the westward-rolling torrent: but as all messages from Western Europe have been met only by that mysterious muteness which, three months and two days since, astounded civilisation in the case of Eastern

New Zealand, we can only assume that these towns, too, have been added to the mournful catalogue; . . . the rate of the slow-riding vapour which is touring our globe is no longer doubtful, having now been definitely fixed by Professor Craven at 100 ½ miles a day—4 miles 330 yards an hour. (86-87)

Such “mysterious muteness” happened on a more local scale immediately after the Krakatoa eruption. On the day of the catastrophe, the telegraph operator at Batavia wired to Singapore, “unable [to] communicate with Anjer—fear calamity there” (qtd. in Simkin and Fiske 14). Shiel’s fictional newspaper article also resonates with the scientific analysis of Krakatoa in the periodical press, which included discussion of the speed at which particles from the eruption spread over the earth’s surface. Adam finds additional scientific analysis when he reads the archives of The Times in their London office, and finds an ongoing debate about the composition of the deadly cloud. He finds an article by a ![]() Dublin scientist named Sloggett to be most persuasive, and Adam’s praise of Sloggett includes the novel’s second explicit reference to Krakatoa:

Dublin scientist named Sloggett to be most persuasive, and Adam’s praise of Sloggett includes the novel’s second explicit reference to Krakatoa:

This article was remarkable for its discernment, because written so early—not long, in fact, after the cessation of communication with

Australia, at which date Sloggett stated that the character of the devastation not only proved an eruption—another, but far greater Krakatoa, doubtless in some South Sea region—but indicated that its most active product must be, not CO, but potassic ferrocyanide (K4FeCn6). (109)

Shiel here uses the public’s memory of Krakatoa and intensifies it, by making his fictional eruption even more catastrophic in force and more deadly in content than the disaster that inspired it.

When Krakatoa exploded on 27 August 1883, it cloaked the surrounding area in darkness, inundated nearby shores, and killed tens of thousands. Over 7,000 miles away in England, sensitive instruments recorded air and sea waves, and observers admired and feared the lurid atmospheric effects. But Krakatoa’s eruption also instigated scientists from varied specialties to cooperate with each other and to seek the public’s help in producing the massive Royal Society Report. The eruption and its aftereffects inspired Tennyson to depict a turning point in Western history and Shiel to imagine a harrowing future of human history’s end. Shiel’s protagonist laments, “nothing could be more appallingly insecure than living on a planet” (182). Krakatoa’s catastrophic eruption and its worldwide effects demonstrated the precariousness, and the interconnectedness, of life on earth.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published January 2013

Morgan, Monique R. “The Eruption of Krakatoa (also known as Krakatau) in 1883.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Altick, Richard D. “Four Victorian Poets and an Exploding Island.” Victorian Studies 3.3 (1960): 249-60. JSTOR. Web. 5 Sept. 2011.

Ball, Patricia M. The Science of Aspects: The Changing Role of Fact in the Work of Coleridge, Ruskin, and Hopkins. London: Athlone, 1971. Print.

Ballantyne, R. M. Blown to Bits, or The Lonely Man of Rakata. 1889. London: James Nisbet & Co., 1894. Project Gutenberg. Web. 20 Jan. 2012.

Bridges, Robert. Eros and Psyche. The Poetical Works of Robert Bridges. 2nd ed. London: Oxford UP, 1964. 87-184. Print.

Chaston, Joel D. “R. M. Ballantyne (24 April 1825 –8 February 1894).” British Children’s Writers, 1800-1880. Ed. Meena Khorana. Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 163. Detroit: Gale Research, 1996. 8-20. Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online. Gale. Web. 23 Aug. 2012.

Daly, Nicholas. “The Volcanic Disaster Narrative: From Pleasure Garden to Canvas, Page, and Stage.” Victorian Studies 53.2 (2011): 255-85. Print.

Flammarion, Camille. Omega: The Last Days of the World. 1893. Intro. Robert Silverberg. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1999. Print.

Hamblyn, Richard. Terra, Tales of the Earth: Four Events that Changed the World. London: Picador, 2009. Print.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “Pied Beauty.” The Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Ed. Norman H. Mackenzie. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1990. 144. Print.

—–. “The Windhover.” The Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Ed. Norman H. Mackenzie. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1990. 144. Print.

Menely, Tobias. “‘The Present Obfuscation’: Cowper’s Task and the Time of Climate Change.” PMLA 127.3 (2012): 477-92. Print.

“The Remarkable Sunsets.” Nature 29.740 (3 Jan. 1884): 222-225. Nature Publishing Group. Web. 27 Oct. 2011.

Roos, David A. “The ‘Aims and Intentions’ of Nature.” Victorian Science and Victorian Values: Literary Perspectives. Eds. James Paradis and Thomas Postlewait. Spec. issue of Annals of the New York Academy of the Sciences 360 (20 Apr. 1981): 159-80. Print.

Shiel, M. P. The Purple Cloud. 1901. Rev. ed. 1929. Intro. John Clute. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2000. Print.

Simkin, Tom and Richard S. Fiske. Krakatau 1883: The Volcanic Eruption and Its Effects. Washington: Smithsonian Institution P, 1983. Print.

Swinburne, Algernon Charles. “A New-Year Ode: To Victor Hugo.” Swinburne’s Collected Poetical Works. Vol. 2. London: William Heinemann, 1927. 865-82. Print.

Symons, G. J., ed. The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society. London: Trübner, 1888. Google Books. Web. 4 Sept. 2011.

Tennyson, Alfred Lord. “St. Telemachus.” The Poems of Tennyson. Ed. Christopher Ricks. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Berkeley: U of California P, 1987. 224-27. Print.

Thornton, Ian. Krakatau: The Destruction and Reassembly of an Island Ecosystem. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1996. Print.

Winchester, Simon. Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883. New York: Harper, 2003. Print.

Wood, Gillen D’Arcy. “1816, The Year without a Summer.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 4 Sep. 2012.

Zaniello, Thomas A. “The Spectacular English Sunsets of the 1880s.” Victorian Science and Victorian Values: Literary Perspectives. Eds. James Paradis and Thomas Postlewait. Spec. issue of Annals of the New York Academy of the Sciences 360 (20 Apr. 1981): 247-67. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] Discussions in English usually refer to the island and volcano as “Krakatoa.” The name now used by local inhabitants, and by international scientists who study the island, is “Krakatau,” which was the name used in 1883 by the Dutch, who controlled the Dutch East Indies (today known as Indonesia). Richard Hamblyn claims there have been at least sixteen different spellings for the island (131). Since this essay is concerned with late-nineteenth-century British representations of the volcano, it adopts the usage in most of its sources and refers to the island and volcano as Krakatoa.

[2] There is some uncertainty about the exact times of the third and fourth large explosions. Ian Thornton estimates the third to have occurred just after 10:00 a.m. (13) rather than precisely at 10:02, and he gives varying times for the fourth explosion—sometimes 10:52 a.m. (14), and sometimes 10:45 a.m (18). Simkin and Fiske note previous reports of 9:58, 10:00, and 10:02 for the time of third great explosion, but decide on 9:58 for their chronology (38), and they give 10:45 as the time of the last explosion but acknowledge that the Royal Society claims 10:52 (40). Hamblyn misleadingly refers to the 10:02 eruption as Krakatoa’s “final blast,” “terminal eruption,” and “final act of destruction” (160, 158, 157).

[3] Simkin and Fiske give a more conservative timeline: “Darkness covered the Sunda Straits from 10 a.m. on the 27th until dawn the next day” (15).

[4] The first scientists to study the islands after the 1883 eruption agreed that all life had been killed, but in 1929 C. A. Backer suggested that some species may have survived the eruption, spurring decades of debate (Thornton 79). Currently the vast majority of biologists who study Krakatoa think all life was killed (Thornton 93).

[5] The authors of the Royal Society’s 1888 report on Krakatoa also emphasized the global reach of Krakatoa’s effects, and the telegraph cables which carried news of them. The Royal Society report begins: “During the closing days of the month of August, 1883, the telegraph-cable from Batavia carried to Singapore, and thence to every part of the civilised world, the news of a terrible subterranean convulsion—one which in its destructive results to life and property, and in the startling character of the world-wide effects to which it gave rise, is perhaps without a parallel in historic times” (Symons 1).

[6] According to David Roos, such a conjunction of science and art would have appealed to Nature’s founder and editor, Norman Lockyer, who wanted the journal’s contents to include all branches of knowledge and its readers and contributors to include both trained scientists and interested laymen. As evidence of Lockyer’s success, Roos cites Hopkins’s letter (173), Lockyer’s own reviews of ![]() Royal Academy of Art exhibitions (172), and the frequent contributions of John Brett, “a member of both the Astronomical Society and the Royal Academy of Arts” (171).

Royal Academy of Art exhibitions (172), and the frequent contributions of John Brett, “a member of both the Astronomical Society and the Royal Academy of Arts” (171).

[7] Altick claims Swinburne “hold[s] the mirror of artifice up to nature” by “using his favorite image of flame and fire to describe sunsets which witnesses agree were marked by diffused rather than concentrated light” (259). Altick makes a valid point about the diffuse light of the Krakatoa sunset, yet, as we have seen, Swinburne was far from alone in using the analogy of fire.

[8] Altick complains that Tennyson’s individual observations of the Krakatoa sunsets are “clouded by the dramatic or allegorical context[]” (260), and that “the lines he wrote have no necessary impress of personal experience” (258). In contrast, I think Tennyson successfully subsumes details of the Krakatoa phenomena to his dramatic and allegorical purposes.

[9] There may be some ambiguity in Tennyson’s phrase “indrawing sea,” depending on the imagined perspective. The sea could be surging in toward the land, or the sea could be drawing itself in away from the shore and stranding a ship that had been anchored. Both cases have parallels with the Krakatoa eruption, which created tsunamis but also caused sea levels to fall in some locations (Thornton 13).

[10] In its happy ending, Blown to Bits differs from other disaster narratives designed to elicit “the pleasure of the reader or viewer in destruction—of people, of property, of hopes” (Daly 255). Ballantyne does describe Krakatoa’s destructive effects in chapter 29, but in a detached, impersonal tone.

[11] Compare the opening of this passage to the nearly identical phrasing in the Royal Society Report: “The Island of Java, with an area about equal to that of England, contains no fewer than forty-nine great volcanic mountains, some of which rise to a height of 12,000 feet above the sea-level. Of these volcanoes, more than half have been seen in eruption during the short period of the European occupation of the island, while some are in a state of almost constant activity. Hot springs, mud-volcanoes, and vapour-vents abound in Java, while earthquakes are by no means unfrequent” (Symons 4).

[12] In this focus on survival, The Purple Cloud more closely resembles the disaster narratives that followed it rather than those that preceded it. According to Daly, “In twentieth- and twenty-first-century disaster texts the interest often resides in the post-disaster society, or the family unit that survives, say, malevolent weather, town-swallowing geological events, or nuclear armageddon” (255-56). Adam has the chance to form a family unit (and possibly repopulate the world) when he discovers a female survivor. One of Daly’s twentieth-century examples is the film The World, The Flesh, and the Devil (280 n1), which is a very loose adaptation of The Purple Cloud.