Abstract

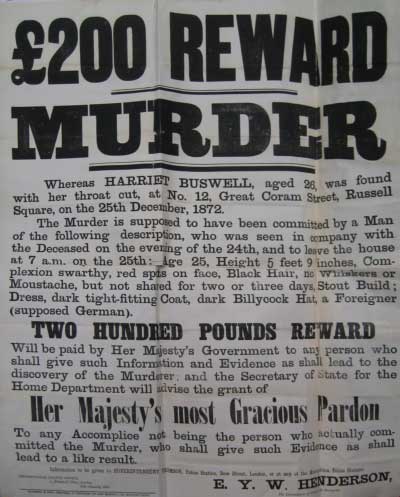

On 24 December 1872, a man murdered Harriet Buswell in her home. The perpetrator was never apprehended. This essay explores the relationship of Buswell’s murder to the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders, which occurred between 31 August and 9 November 1888.

People often assume that the “Jack the Ripper” case (1888), in which an unknown assailant or assailants murdered five women, was the definitive “cold case” of the nineteenth century. It has spawned books, movies, television shows, and countless theories about the perpetrator. Many writers have remarked on the symbolic potency of the “Ripper.” One has described him as a “blank slate” to which we can “attribute the most horrific appetites without troubling ourselves” about the source or even the historical context, since his identity remains unknown (McLaren xii). The Ripper case has dominated our perception of murder in the period, but this vision of nineteenth-century criminal activity and detection has been distorted by our broad disconnection from the deeper historical context the Victorians had for the case.

Before Jack the Ripper came Harriet Buswell. Called “The ![]() Great Coram Street-Murder” in the press, Buswell’s murder in 1872 preceded the Ripper case by a full sixteen years. In fact, what the Victorians knew about murder mysteries generally, and the murder of prostitutes in particular, was significantly affected by this earlier event. Buswell’s case gives us a glimpse into what the Victorians thought about unsolved murder and criminal detection in police history prior to the Ripper scandal. It also provides a meaningful perspective on the differences between unsolved murder in 1872 and 1888.

Great Coram Street-Murder” in the press, Buswell’s murder in 1872 preceded the Ripper case by a full sixteen years. In fact, what the Victorians knew about murder mysteries generally, and the murder of prostitutes in particular, was significantly affected by this earlier event. Buswell’s case gives us a glimpse into what the Victorians thought about unsolved murder and criminal detection in police history prior to the Ripper scandal. It also provides a meaningful perspective on the differences between unsolved murder in 1872 and 1888.

The Ripper case is complex; here, I will focus on the key themes that have contributed to a contemporary narrative about Victorian murder. Even this is difficult, however, because the crimes were unsolved and there are many uncertainties about them. We don’t know whether there was only a single perpetrator; whether the murders were, in fact, connected; or whether there were additional murders committed by the same perpetrator that have not come to the fore in the investigations. I proceed, therefore, with what have been called the “canonical five,” murders accepted by a broad range of historians and “Ripperologists” as having been committed by the same perpetrator.

The Ripper murders occurred in London, primarily in the poor community of ![]() Whitechapel (one of the murders crossed the boundary into

Whitechapel (one of the murders crossed the boundary into ![]() the City, the business district of London). All of the victims were prostitutes whose throats had been cut, and all but one of the bodies were mutilated. The single victim who escaped mutilation was Elizabeth Stride, and most critics believe that, in this case, the murderer was interrupted in the midst of the crime. The murders all happened at night on densely populated streets, and, while four of them took place out in the open, no witnesses saw the perpetrator well enough to identify him or offer a detailed description. There was no clear motive for the crimes, and the murderer was never brought to justice. Many writers discussing the crime in the nineteenth century and today have claimed that the murderer was a sexual deviant, particularly since the murders were enacted on prostitutes and much of the physical mutilation focused on the abdomen.

the City, the business district of London). All of the victims were prostitutes whose throats had been cut, and all but one of the bodies were mutilated. The single victim who escaped mutilation was Elizabeth Stride, and most critics believe that, in this case, the murderer was interrupted in the midst of the crime. The murders all happened at night on densely populated streets, and, while four of them took place out in the open, no witnesses saw the perpetrator well enough to identify him or offer a detailed description. There was no clear motive for the crimes, and the murderer was never brought to justice. Many writers discussing the crime in the nineteenth century and today have claimed that the murderer was a sexual deviant, particularly since the murders were enacted on prostitutes and much of the physical mutilation focused on the abdomen.

In her brilliant study of sexual danger in Victorian London, Judith Walkowitz suggests that there was no “historical precedents for the Whitechapel ‘horrors’” (Walkowitz, City 196). However, late Victorian writers on unsolved murder cases often mentioned Harriet Buswell’s murder in the same breath with the Ripper murders (“Mysteries of Police and Crime” 786). This was, in part, due to some striking similarities in the crimes. Harriet Buswell, murdered in her bed early in the morning on December 25th in 1872, had her throat cut in two places like many of the Ripper victims. Like the Ripper victims, she had been a prostitute. Similarly, while arrests were made in the Buswell case, no one was ever convicted of the crime. The cases share enough parallels that former ![]() Scotland Yard detective and authority on Jack the Ripper, Trevor Marriot, argues in his new book on murder, due out in 2013, that Buswell was an early Ripper victim (Marriot).

Scotland Yard detective and authority on Jack the Ripper, Trevor Marriot, argues in his new book on murder, due out in 2013, that Buswell was an early Ripper victim (Marriot).

These similarities are compelling and suggest to us that we must examine the public response to the Ripper case against the backdrop of the Buswell case. Just as significantly, however, the differences help us understand why the Ripper murders dominate our perception of murder in the nineteenth century.

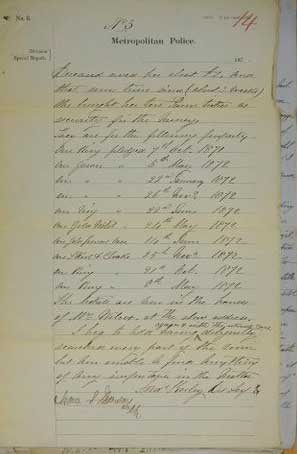

The police files of Buswell’s case reveal Buswell to have been a bright, intriguing, and genuinely likeable woman, who often inspired earnest devotion in the people with whom she engaged. They also evidence an active police force, working energetically to respond to each and every one of the hundreds of informational letters from the public—some suggesting perpetrators or clues, others proposing an interpretation of the crime based on the news coverage of the Coroner’s Inquest, and others critiquing the police’s failure to solve the case.

Figure 1: George Wright, bill for Mrs. Burton [Harriet Buswell], n.d., MEPO 3/114, National Archive of Great Britain

On that December night, Buswell had met a man, eaten dinner with him at a local restaurant, ridden home with him on an omnibus (at that time, horse-drawn), stopped with him at a grocer’s to purchase nuts and fruit, and, finally, brought her companion to her boarding house on Great Coram street. The landlady opened the door for them, and, after the man stumbled up the stairs alone, Buswell had a glass of stout with her landlady before heading up to her death in her apartment (“The Great Coram-Street Murder” 8). Along the way, the number of people who later became “witnesses” grew, and they were able to offer detailed descriptions of the supposed murderer. While most of them agreed that the man with whom Buswell went home that night was a foreigner, likely a German, and they could describe his attire with some uniformity (fairly significant evidence in a period in which people often had few changes of clothes), the murderer was never found.

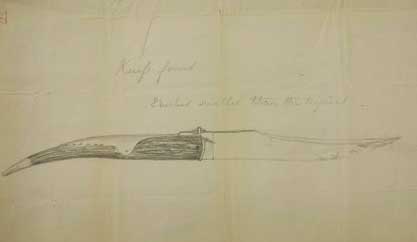

Figure 2: “Knife Found,” Metropolitan Police, E Division, MEPO 3/111, National Archive of Great Britain

Finally, a promising arrest was made in January, 1873. Three of the chief witnesses in the case positively identified Dr. Gottfried Hessel, a minister immigrating with a group of Germans to South America. His ship had stopped for repairs in ![]() Ramsgate, and he had, in fact, traveled to a hotel in the city on December 22nd and been in London on the night of the crime. His defense attorneys argued, however, that his boots were outside the door of his room on the night of the murder; that he had been ill in his room for several days; and that several witnesses could corroborate this story. Thus, they argued, he had been incapable of committing murder.

Ramsgate, and he had, in fact, traveled to a hotel in the city on December 22nd and been in London on the night of the crime. His defense attorneys argued, however, that his boots were outside the door of his room on the night of the murder; that he had been ill in his room for several days; and that several witnesses could corroborate this story. Thus, they argued, he had been incapable of committing murder.

Of course, it was far more than the location of his boots that made him an unlikely murderer to the public. Though a foreigner (something that might have been enough to raise people’s suspicions in 1873), Hessel was a calm, soft-spoken, educated clergyman and a married man—all of which were read as signs of his respectability. In spite of the fact that the maid at the lodging house claimed that she had been given several bloody handkerchiefs to wash by Hessel’s wife, the strong evidence in his favor exonerated him in the eyes of the court and the public. The Magistrate freed him with commendatory remarks on his behavior and insisted upon his innocence. The police appeared foolish for even bringing him forward to the courts as a suspect when he had such a clear alibi and cut an unlikely figure for a murderer. Hessel’s discharge seemed to bring the painful drama to an end; it closed the Buswell case for the public, if not for the police, even though the perpetrator had never been nabbed.

This was not so with the Ripper crimes, which differed in many significant ways. The police were developing increasingly sophisticated and scientific detection methods, and the case was conducted by the elite detective unit at Scotland Yard, rather than one of the divisional police units. During the Buswell investigation, the public believed that the police had bungled the case, rather than that the criminal was particularly slippery; whereas in the Ripper case, in spite of some stringent criticism of the detectives, the murderer was perceived to be especially shrewd. Moreover, the deluge of killings in the Ripper case—murder following upon murder, week after week—had left the public in a much greater state of agitation. However horrifying Buswell’s murder had been, it only happened once. Finally, no one had seen or could identify the perpetrator in the Ripper case, whereas there were dozens of witnesses in Buswell’s. Witnesses could describe Buswell’s murderer down to the blemishes on his face. The Ripper seemed more like smoke or a ghoul than an ordinary man. All of these factors steeply increased public anxiety.

Though the Buswell crime had prepared the Victorian populace for the possibility of a gruesome unsolved murder, her death seemed a singular event, which made it easier for the public to read it as anomalous or to dismiss it as an “ordinary” robbery or crime of passion. In fact, the press and publications on the case continued to minimize the potential concerns it raised about psychologically motivated violence against women by insisting that the murderer had been motivated by the desire to steal her scant possessions or that he was the agent of someone with a secret vendetta against Buswell—possibly her child’s father or a former lover (Peacock 9). With the rising number of mutilated bodies in 1888, however, motives of theft or rage against the victims seemed a ridiculous prospect. Instead, primarily psychological motives were proposed, most of which argued that the murderer hated prostitutes or women in general (a doctor with a special knowledge of venereal disease had suspected this as a motive in Buswell’s case [Acton], but this didn’t get much traction in the mainstream media).

A deranged but cunning serial killer can induce much more fear than a thief or angry lover, regardless of their similar modus operandi. In the Ripper case, too, the police—perhaps having learned their painful lesson in the Buswell murder—avoided the arrest of those outside the working class. As Walkowitz puts it, “[d]espite the theories about upper-class perverts and maniacal reformers, police still arrested the same motley collection of ![]() East End down-and-outers” (City 212). Unspoken boundaries may have undermined the investigation and had the effect of helping the murderer seem almost super-human in his power to escape detection.

East End down-and-outers” (City 212). Unspoken boundaries may have undermined the investigation and had the effect of helping the murderer seem almost super-human in his power to escape detection.

The Ripper crimes still have the power to shock even without reference to the social context; however, we can better understand why they have stayed with us with such tenacity if we see them as the Victorians would have—against the backdrop of their differences from the most similar crime that preceded them. Though the murderer remained undiscovered in both cases, the Ripper crimes resisted the stories that the Victorians had told about the Buswell case—that it was motivated by robbery or jealousy. This difference makes clear why the 1888 events have so thoroughly dominated our sensibility of crime in the nineteenth century while Buswell has disappeared from our cultural memory. Buswell’s case could be dispatched by the public with narratives that explained away its violence. Strikingly, the Ripper’s could not. This contrast has helped the Ripper continue to haunt us to this day.

published December 2012

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Tromp, Marlene. “A Priori: Harriet Buswell and Unsolved Murder Before Jack the Ripper, 24-25 December 1872.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Acton, W[illiam]. “Reflections on the Possible Motives for the Coram-Street Murder.” The Lancet 101 (18 January 1873): 115. ScienceDirect Journals. Web. 6 June 2012.

Brown, Howard G. “Trips, Traps and Tropes: Catching Thieves in Post-Revolutionary Paris.” Police Detectives in History, 1750-1950. Eds. Clive Emsley and Haia Shpayer-Makov. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006: 33-60. Print.

Dimock Drapers, High Holborn. Bill for silks, satins, and flannels (June 10, 1872), MEPO 3/114, National Archive of Great Britain. Print.

Emsley, Clive. Crime, Police and Penal Policy: European Experiences 1750-1940. New York: Oxford, 2007. Print.

—. The English Police: A Political and Social History. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Pearson Education Limited, 1996. Print.

“The Great Coram-Street Murder.” The Times (December 28, 1872): 8. British Library Newspapers Online. Web. 8 May 2011.

Kerley, Fred, Det Sergeant. “Harriet Buswell Murder: German Consul, London.” Metropolitan Police, E Division Special Report (January 10, 1873) MEPO 3/112, National Archive of Great Britain. Print.

“Knife Found.” Metropolitan Police, E Division, MEPO 3/111, National Archive of Great Britain. Print.

Lewis Grave and Company, bill for Mrs. Burton [Harriet Buswell], n.d., National Archive of Great Britain. Print.

Marriott, Trevor. The Evil Within. London: John Blake Publishing, 2013. Print.

McLaren, Thomas. A Prescription for Murder: The Victorian Serial Killings of Dr. Thomas Neill Cream. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995. Print.

“Mysteries of Police and Crime.” The Graphic (December 17, 1889): 786. British Library Newspapers Online. Web. 8 May 2011.

Peacock, Waldemar Fitzroy. Who Committed the Great Coram Street Murder? An Original Investigation. The Track Shown; The Criminal Indicated. London: F. Farrah, 282, Strand, [1873]. Print.

Popham, R. H., MD. Bill for medical services (March 1872), MEPO 3/114, National Archive of Great Britain. Print.

Reward Poster. Metropolitan Police, E Division, MEPO 3/110, National Archive of Great Britain. Print.

Shpayer-Makov, Haia. “Explaining the Rise and Success of Detective Memoirs in Britain.” Police Detectives in History, 1750-1950. Eds. Clive Emsley and Haia Shpayer-Makov. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006: 103-134. Print.

Walkowitz, Judith. City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992. Print.

Walkowitz, Judith. Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class, and the State. New York: Cambridge UP, 1982. Print.

Wright, George. Bill for Mrs. Burton [Harriet Buswell], n.d., MEPO 3/114, National Archive of Great Britain. Print.