Abstract

On 28 August 1789, William Herschel began exploring the cosmos with his forty-foot telescope, which would remain the largest in the world for the next half century. Though the giant instrument gave Herschel and others greater access to the deep space of the cosmos, its cultural impact extended well beyond the realm of science.

In 1781, William Herschel’s star literally rose when his discovery of a new planet caused such excitement, the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande proposed it be named “Herschel” (Clerke 25). The discovery of Uranus catapulted Herschel into the position of the King’s Astronomer, and a few years later, with financial assistance from King George, he began work on what would be his most ambitious project: the construction of a forty-foot telescope. Herschel began the project in 1785 in Old Windsor, but less than a year later he and his sister Caroline, who was also an astronomer, were informed by the “litigious” owner of their rental house that, since the telescope would increase the property value, their rent would be raised annually (Sidgwick 129). They subsequently left Old Windsor and established a permanent residence near ![]() Windsor Castle at

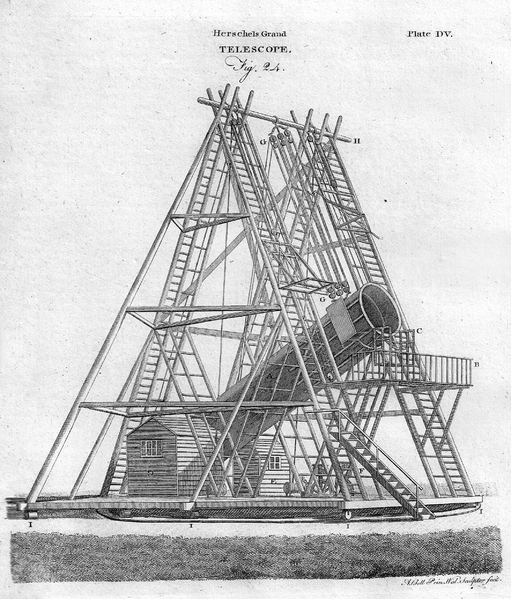

Windsor Castle at ![]() Slough, where they set up an observatory. Over the next few years, William oversaw the construction of the largest telescope in the world, a standing it would maintain for the next half century, and on 24 August 1789, he looked through the giant instrument for the first time. Four nights later, his telescopic viewing yielded a major discovery—the sixth satellite of Saturn—and he thereby designated 28 August 1789 as the date of completion of the forty-footer (Sidgwick 135-36; Herschel “Description” 350). The cultural impact of the giant telescope was enormous, though not for reasons anyone, including Herschel, expected. (See Fig. 1.)

Slough, where they set up an observatory. Over the next few years, William oversaw the construction of the largest telescope in the world, a standing it would maintain for the next half century, and on 24 August 1789, he looked through the giant instrument for the first time. Four nights later, his telescopic viewing yielded a major discovery—the sixth satellite of Saturn—and he thereby designated 28 August 1789 as the date of completion of the forty-footer (Sidgwick 135-36; Herschel “Description” 350). The cultural impact of the giant telescope was enormous, though not for reasons anyone, including Herschel, expected. (See Fig. 1.)

During his career, Herschel was as renowned as a maker of telescopes as he was as an astronomer, and he oversaw the construction of several hundred instruments, which were sold in England and on the continent. Though he contributed significantly to popularizing astronomy through this cottage industry, his dream was not to be an entrepreneur, as his sister indicates in a recollection of 1785:

It seemed to be supposed that enough had been done when my brother was enabled to leave his profession that he might have time to make and sell telescopes. [Before receiving the patronage of King George, Herschel earned a living as a music teacher, organist, and composer.] The King ordered four ten-foot himself, and many seven-foot besides had been bespoke, and much time had already been expended on polishing the mirrors for the same. But all this was only retarding the work of a thirty or forty-foot instrument, which it was my brother’s chief object to obtain as soon as possible; for he was then on the wrong side of forty-five, and felt how great an injustice he would be doing to himself and to the cause of Astronomy by giving up his time to making telescopes for other observers. (Mary Herschel 56-57)

J. A. Bennett, who describes the evolution of Herschel’s telescopes, which ranged in size from seven-feet to forty-feet, specifies the impetus behind Herschel’s desire to construct a very large instrument: “The sweeps [performed by the twenty-foot telescope] had . . . collected a great many specimens of nebulae, but Herschel was still convinced that they were all distant clusters of stars. . . . The greater resolving power of a larger telescope would provide further evidence for his view of the heavens as a distribution of stars moulded and arranged by the force of gravity” (88).

Though a desire to test his hypothesis regarding the nature of nebulae impelled Herschel to build the forty-footer, as the largest telescope in the world it drew attention to other breakthroughs he had already made in understanding the cosmos. To this day, Herschel is best known for his discovery of Uranus, but his contributions to astronomy exceeded his sighting a new planet: he established the field of sidereal, as opposed to planetary, astronomy; he discovered thousands of nebulae and double stars; and he put forward the arresting idea that the universe, including our own galaxy, was both limitless and mutable.

Telescopic discoveries by Herschel and his fellow scientists caused theologians to reconsider conventional views of God and humankind. Thomas Dick, a Scottish minister and science teacher who makes a passing reference to Herschel’s forty-foot telescope in his book The Sidereal Heavens,[1] writes with exhilaration of the power of such instruments:

Beyond the range of natural vision the telescope enables us to descry numerous objects of amazing magnitude; and, in proportion to the excellence of the instrument and the powers applied, objects still more remote in the spaces of immensity are unfolded to our view, leaving us no room to doubt that countless globes and masses of matter lie concealed in the still remoter regions of infinity, far beyond the utmost stretch of mortal vision. But huge masses of matter, however numerous and widely extended, if devoid of intelligent beings, could never comport with the idea of happiness being coextensive with the range of the Creator’s dominions. . . . To consider creation, therefore, in all its departments, as extending throughout regions of space illimitable to mortal view, and filled with intelligent existence, is nothing more than what comports with the idea of HIM who inhabiteth immensity, and whose perfections are boundless and past finding out. (255)

The Rev. Dionysius Lardner, an astronomy professor at the ![]() University of London, also pursues the possibility of extraterrestrial life. Referring to other “orbs” in the universe, he writes:

University of London, also pursues the possibility of extraterrestrial life. Referring to other “orbs” in the universe, he writes:

Have not their intelligent beings, capable of perceiving the laws of the universe, and therefore at once manifesting and glorifying the power, the wisdom, and the goodness of the infinite and incomprehensible Centre of all Existence? Are these rolling worlds like ours in all things else, and yet inferior to ours in that? Or is it not probable, that they are the habitations of classes of creatures excelling us as far in intellectual power, as some of those planets exceed ours in magnitude and apparent importance. (18)

The excitement over telescopic discoveries and their implications for other cultural arenas, such as theology, was not shared by everyone, however. To some, telescopes were aggressive instruments since they dared to intrude upon the heavens. What follows are the views of three English poets, two of whom challenged the legitimacy of the telescope and a third who accepted its authority. Other Romantic-era writers weighed in on the value of telescopes, but, through these three poets, one gets a glimpse of how Herschel’s giant instrument put astronomy front and center in public consciousness and stirred up a debate over the merits of such scientific apparatuses.

In 1797 and 1798, William and Dorothy Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge viewed the night skies regularly in Nether Stowey, as Thomas Owens has described. Wordsworth’s interest in science has been well documented, but it is evident from the references to telescopes in his writing that he regarded them with a measure of wariness.[2] Though, as Owens points out, Wordsworth refers to a telescope in his 1798 poem “The Thorn,” the narrator indicates he uses the instrument for lateral rather than vertical viewing: “For one day with my telescope, / To view the ocean wide and bright, / . . . / I climbed the mountain’s height . . .” (170-74). Wordsworth’s decision not to introduce the telescope in “The Thorn” as a device for stargazing is somewhat surprising in light of the history of the poem, recounted by Owens:

Inspiration for “The Thorn” came from issues of the Monthly Magazine of February to December, 1796, that were amongst the first consignment of books that Wordsworth received at

Alfoxden from James Losh, and which included important source material for the poem in the form of William Taylor’s translations of poems by Bürger. . . . these papers also contained an enormous double-page illustration of Herschel’s forty-foot telescope, complete with a lengthy description of its operative and magnifying capacity. . . . (27)

The two-page spread of Herschel’s forty-footer either made little impression on Wordsworth, or the poet conveyed his tacit rejection of it by the limited use of the telescope in “The Thorn.”

In his 1806 poem “Star-Gazers,” Wordsworth is direct in communicating his skepticism of telescopes as astronomical instruments. His portrayal of a public viewing of the night sky as a theatrical event—“The Show-man chooses well his place; ‘tis Leicester’s busy Square”—reduces the telescope to a prop that turns the heavens into a spectacle (5). Though he describes everyone in the crowd as waiting impatiently to look through the instrument, the poem concludes in melancholy. With a sentiment that years later would be echoed by Walt Whitman’s Learn’d Astronomer, Wordsworth intimates that the atomizing of the cosmos through science depletes it of its soul:

Whatever be the cause, ’tis sure that they who pry and pore

Seem to meet with little gain, seem less happy than before:

One after One they take their turn, nor have I one espied

That doth not slackly go away, as if dissatisfied. (29-32)

In a note about the poem, Wordsworth writes that the event was “Observed by me in Leicester-square, as here described” (Selected Poems and Prefaces 568). Since at the viewing he chose to observe the observers rather than the stars, the stars were twice mediated for him. There is no hint in the poem that Wordsworth sees the irony in which he has implicated himself: by reading the observers’ faces, which function as a reflecting lens, he, in effect, mimics the operation of the telescope.

In Book II of The Excursion, a telescope makes a cameo appearance, but it appears only to disappear. Wordsworth’s description of the unkempt interior of a cottage includes a “shattered telescope, together linked / By cobwebs,” a visual prediction of what he evidently saw as its inevitable obsolescence (667-68). Unencumbered by astronomical devices, Wordsworth holds fast to conventional views of the universe throughout most of his poetry. In “If Thou Indeed Derive Thy Light from Heaven,” for example, he declares the stars to be “the undying offspring of one Sire,” implying that cosmic phenomena have a divine source and are as immortal as their Maker (14). The poem was first published in 1827, but the above line was one of several lines added to the poem late in his career in 1837 (Selected Poems and Prefaces 576).

Marilyn Gaull has argued that Herschel did exert some influence on Wordsworth, evidenced in a change he made to The Prelude in 1839. The amended version of a passage in Book 6 describes the effect “geometric science” had on him:

. . . I [did] meditate

On the relation those abstractions bear

To Nature’s laws, and by what process led,

Those immaterial agents bowed their heads

Duly to serve the mind of earth-born man;

From star to star, from kindred sphere to sphere,

From system on to system without end. (122-28)

Gaull’s observation that Wordsworth “contain[s] Herschel’s universe in Newton’s laws” is astute (40). To be precise, however, the poet contains one aspect of Herschel’s universe—deep space. Though Wordsworth portrays cosmic phenomena as existing “without end,” the lyrical cadence and harmonious description of the cosmos suggest he sidesteps Herschel’s more radical claim that the cosmos is in a state of dissolution. The influence of Herschel on Wordsworth is further mitigated in the poem by the context in which stars, spheres, and systems are mentioned: the narrator is meditating, not stargazing. Moreover, his meditation is inspired by mathematics, not a telescope, a point he amplifies in the passage that follows: geometric science, he argues, provided him with “A type, for finite natures, of the one / Supreme Existence, the surpassing life / Which – to the boundaries of space and time, / . . . [is] / Superior, and incapable of change . . .” (6.133-37). Wordsworth’s sublime description of the ability of math to enlarge one’s perspective suggests that it fulfilled for him the function of the telescope, rendering mechanical instruments, including Herschel’s forty-footer, unnecessary.

The dismissal of the telescopic probing of the heavens by one of England’s preeminent thinkers gives one pause. The telescopes Herschel designed and built were hardly a sideshow; they altered dramatically the stubbornly held view of the universe as an enclosed dome with stationary stars and revealed it to be unbounded space with stars in flux. Wordsworth’s resistance to such instruments was, no doubt, strengthened by his seeing more clearly than most the threat of encroaching technology, which would redefine what it meant to be human. He was not, however, the only poet to prosecute the cultural value of the telescope. William Blake also rejected it on epistemological grounds though, unlike Wordsworth, he did not have a sentimental view of the naked eye.

To Blake, seeing was an imaginative act, as he concisely states in a letter: “Every body does not see alike” (702). Though today such an observation seems obvious to the point of being unworthy of mention, for nearly two centuries, telescopes, along with microscopes, had literalized the theory that perception is mechanical and uniform, a view of perception that, to Blake, was antagonistic to both optical and imaginative vision. In his annotations to Thornton’s translation of The Lord’s Prayer, Blake makes a snide reference to “a Lawful Heaven seen thro a Lawful Telescope,” insinuating that the telescope is part of a government conspiracy to regulate perception (668). He further goes on to parody the well-known opening lines of The Lord’s Prayer: “Our Father Augustus Caesar who art in these thy <Substantial Astronomical Telescopic> Heavens” (669).[3] Blake’s hyperbolic mockery sounds comical, but underlying those remarks is a serious concern. During the Romantic era, astronomy became a public enterprise as more telescopes were built and made accessible to people in all walks of life. From Blake’s perspective, this democratizing of science had a downside, however: it implanted a mechanical eye in people across Europe.

In his poem Milton, Blake suggests that telescopes shrink the universe of the viewer:

The Sky is an immortal Tent built by the Sons of Los

And every Space that a Man views around his dwelling-place:

Standing on his own roof, or in his garden on a mount

Of twenty-five cubits in height, such space is his Universe. (29:4-7)

Blake’s description of the dwelling-place from which a man observes the sky conveniently evokes an image of the Herschels’ viewing sites. The roof of Caroline’s cottage at Slough was a viewing platform from which she conducted sweeps of the sky with a smaller instrument while the main observatory with the giant telescope was situated nearby in a garden. But Blake’s reference to Herschel is even more acute in the above passage. To peer through the forty-footer, an observer had to climb a flight of stairs to a gallery and then scale a ladder to the observing-platform. Though the distance from the ground to the observing-platform was shorter than what Blake describes in the poem, Herschel’s giant telescope (whose tube, to be exact, was 39’, 4”) was approximately twenty-six cubits in length. Blake’s math is even more precise when one considers a detail Herschel provides in his description of the instrument: “the observer is elevated 30 or 40 feet above the assistant [who records the measurements]” (“Description” 365, 385). 25 cubits is the rounded-off average of 30 feet and 40 feet.

Blake further depicts in Milton the malleability of the universe, which, he argues, conforms to the imagination of the person who views it: “The Starry heavens reach no further but here bend and set / On all sides & the two Poles turn on their valves of gold: / And if [the observer] move his dwelling-place, his heavens also move” (29:10-12). Since the heavens move with the observer, we might transpose one of Blake’s proverbs from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and conclude that, where man is not, the cosmos is barren (9.68). Blake’s portrayal of a person’s perception of the universe concludes with a direct critique of mechanical visual aids:

As to that false appearance which appears to the reasoner,

As of a Globe rolling thro Voidness, it is a delusion of Ulro

The Microscope knows not of this nor the Telescope. they [sic] alter

The ratio of the Spectators Organs but leave Objects untouchd. (29.15-18)

The unnamed “reasoner,” is quite likely Herschel, who, when looking through a telescope, saw stars as “Globe[s] rolling thro Voidness.” Blake rejects the claim that the telescope has the capacity to extend vision and portrays it as an instrument that does just the opposite. In his words, it contributes to the delusion of “Ulro,” his term for the lowest level of perception. In an article on Blake and scientific objects, Mark Lussier remarks on the above passage, “Instruments simply alter the ratio of ‘Organs’ yet impact not ‘Objects’ thereby widening the gap between imaginative and sensory experience . . .” (122). By altering the “ratio of the Spectators Organs,” which is what happens when you look through any configuration of convex or concave mirrors, the telescope, from a Blakean perspective, does not enhance vision; it merely creates an alternative distortion. Blake’s argument in opposition to the telescope is compelling: adding a filter to the human eye, which is already an instrument of mediation, will not lead to unmediated perception.

Ironically, Blake’s observation that “Every body does not see alike” resonates with a statement made by Herschel seventeen years earlier:

Seeing is in some respect an art, which must be learnt. To make a person see with such a power is nearly the same as if I were asked to make him play one of Handel’s fugues upon the organ. Many a night have I been practising to see, and it would be strange if one did not acquire a certain dexterity by such constant practice. (qtd. in Lubbock 101)

Anna Henchman has noted, “The act of ‘practicing to see’ is not available to a telescope; it must be performed by a human agent. Only with the help of an experienced eye and a synthesizing mind can the visual information gathered through a telescope be properly understood; the expertise of the scientist who learns to see makes this material intelligible” (24). The interplay between the viewer and the telescope is particularly interesting in light of Herschel’s intimation that the telescope performs an imaginative role for viewers. After noting the dates when he discovered two of Saturn’s satellites with the forty-footer, he admits, “It is true that both satellites are within reach of the 20-feet telescope,” and then states, “but it should be remembered, that when an object is once discovered by a superior power, an inferior one will suffice to see it afterwards” (“On the Power” 77). Though Herschel and Blake diverge on the value of the telescope, they both reject the idea that seeing is passive, mechanical, and uniform among all people and argue that it engages the imagination.

Any affinity between Herschel and Blake, empiricist and metaphysician, is counterintuitive and, therefore, all the more intriguing. Along with conceiving of seeing in a way that would later be associated with Blake, Herschel (like Blake) participates in both invention and execution, constructing the medium through which he sees the universe.[4] In a letter to her nephew, written in 1786, Caroline Herschel provides a close-up of the building of the technological behemoth, revealing how intimately her brother was involved in the execution of his design:

It would be impossible for me, if it were required, to give a regular account of all that passed around me in the lapse of the following two years, for they were spent in a perfect chaos of business. The garden and workrooms were swarming with labourers and workmen, smiths and carpenters going to and from between the forge and the forty-foot machinery, and I ought not to forget that there is not one screw-bolt about the whole apparatus but what was fixed under the immediate eye of my brother. I have seen him lie stretched many an hour in a burning sun, across the top beam whilst the iron work for the various motions was being fixed.

At one time no less than twenty-four men (twelve and twelve relieving each other) kept polishing day and night; my brother, of course, never leaving them all the while, taking his food without allowing himself time to sit down to table. (Mary Herschel 73)

M. Pictet, a professor of astronomy from ![]() Geneva who visited Herschel in 1786, later marveled at his dual capacities: “Herschel has shown himself as great a Mechanician as a consummate Astronomer . . .” (qtd. in Lubbock 159). In an article published the following year, he provides a first-hand account of the polishing of the mirror of the forty-footer:

Geneva who visited Herschel in 1786, later marveled at his dual capacities: “Herschel has shown himself as great a Mechanician as a consummate Astronomer . . .” (qtd. in Lubbock 159). In an article published the following year, he provides a first-hand account of the polishing of the mirror of the forty-footer:

It follows that besides the most perfect polish the mirror of the telescope must have a parabolic figure. The work, as directed by Herschel, to achieve these two conditions, would make a subject for a picture. In the middle of his workshop there rises a sort of altar; a massive structure terminating in a convex surface on which the mirror to be polished is to rest and to be figured by rubbing. To do this the mirror is encased in a sort of twelve-sided frame, out of which protrude as many handles which are held by twelve men. . . .

The mirror is moved slowly on the mould, for several hours at a time and in certain directions, which by pressing more on certain parts of the surface than on others, tends to produce the parabolic figure.

It is then removed on a truck and carried to the tube, into which it is lowered by a machine expressly contrived for the purpose. This labour is repeated every day for a considerable time and by the observations he makes at night, Herschel judges how nearly the mirror is approaching the standard he desires. (qtd. in Lubbock 158)

Pictet’s portrayal of the work scene as an altar, as well as his note that the mirror was polished by twelve men who strived to attain the high standard set by their master, is suggestive. Herschel was revered by those close to him. As an unusually skilled seer, he was in their eyes a prophet of sorts in the biblical sense of the word.[5] If, as Herschel suggests, seeing is indeed an art, then science, an enterprise that rests heavily on observation, is not only a religion (as Herschel’s followers and admirers conveyed by their devotion to him) but also an art, a view that Blake himself held.[6]

Blake’s shortsightedness in recognizing the common ground he shared with Herschel was inevitable in light of his rejection of empirical science, both in theory and in practice. Even if Blake had had sufficient resources, it is improbable he would have joined the stream of visitors who visited Slough to look through the forty-footer. Those curious celestial sightseers, however, did include Lord Byron, and the effect on him was profound, as he indicates in an 1813 letter: “the comparative insignificance of ourselves & our world when placed in competition with the mighty whole of which it is an atom . . . first led me to imagine that our pretensions to eternity might be over-rated” (Letters and Journals 3: 64).

Byron’s response was hardly unique. The telescopic view of the cosmos in the nineteenth century was a jolt to an earth-centric perspective of the universe. When Herschel sighted Uranus, he gained instant celebrity among the public, as well as patronage from the king, who, as noted earlier, subsidized the building of the large telescope. Notwithstanding the enthusiastic reaction, the discovery of Uranus did not change the course of science but simply identified another cosmic body on the well-established celestial map. A few years later, however, Herschel made a discovery that all but shredded that map. Through his telescopic viewing, he recognized that some nebulae originate in the decay of other nebulae, and, as mentioned earlier, he argued that the cosmos is always in a state of dissolution and reconstitution (Scientific Papers 1: 252). In one of his papers, he zeroes in on our own galaxy and offers unsettling news: “it is evident that the milky way must be finally broken up, and cease to be a stratum of scattered stars” (Scientific Papers 2: 540). He further argues, “the breaking up of the parts of the milky way affords a proof that it cannot last for ever [and] it equally bears witness that its past duration cannot be admitted to be infinite” (Scientific Papers 2: 541). For an astronomer to announce in the late eighteenth century that our own galaxy was gradually dissolving was startling. Herschel’s high-powered telescopes, jutting into the air, pierced the calm and stable dome that had sheltered the thinking of lay people and many astronomers from time immemorial.

The evidence that Byron’s view of the cosmos was agitated by Herschel’s forty-footer is overt in his poem “Darkness,” but it can also be detected in Manfred, in which he dramatizes the cultural ramifications of Herschel’s theory. Early in the poem, Manfred invokes the “Spirits of earth and air,” declaring that they are subject to “a power . . . / Which had its birth-place in a star condemn’d, / The burning wreck of a demolish’d world, / A wandering hell in the eternal space . . .” (1.1.41-46). The seventh spirit who responds to Manfred’s call provides a backstory that suggests Manfred has the same trajectory as a stray comet:

The star which rules thy destiny

Was ruled, ere earth began, by me:

It was a world as fresh and fair

As e’er revolved round sun in air;

Its course was free and regular,

Space bosom’d not a lovelier star.

The hour arrived—and it became

A wandering mass of shapeless flame,

A pathless comet, and a curse,

The menace of the universe;

Still rolling on with innate force,

Without a sphere, without a course,

A bright deformity on high,

The monster of the upper sky!

And thou! beneath its influence born. . . . (1.1.110-24)

From Byron’s poetry, especially Manfred, it is tempting to consider that the legacy of Herschel’s telescopes (including the forty-footer)—namely, that we live in an unfathomable cosmos in a state of dissolution—may have exacerbated his mood swings between euphoria and despair. The spirit’s associating Manfred with the star that rules his destiny, a star that initially was a “fresh and fair” world but then turned into “A wandering mass of shapeless flame,” further suggests that Manfred, and by extension Byron, is bipolar because as a part of the cosmos he is also bi-solar.

Byron’s tersest description of the inescapable link between the quantum and the cosmic appears in “Heaven and Earth” where he writes of a “wandering star, which shoots through the abyss, / Whose tenants dying, while their world is falling, / Share the dim destiny of clay” (1.1.87-89). In his poem “The Dream,” Byron alludes to the role of the telescope in exposing this demise. By presenting the nature of truth through the metaphor of a telescope, he intimates the veracity of the instrument: “the telescope of truth . . . / . . . strips the distance of its phantasies, / And brings life near in utter nakedness, / Making the cold reality too real!” (180-83). He abandons the metaphor in the final stanza of “The Vision of Judgment” and states directly, “The telescope . . . / . . . kept my optics free from all delusion” (842-43). It must have come as no small surprise to Byron, who was openly dismissive of religion, to find that the telescope, which he revered for its undistorted view of the universe, had awakened in him a deeper consciousness. In a note, he writes: “The Night is also a religious concern—and even more so—when I viewed the Moon and Stars through Herschell’s [sic] telescope—and saw that they were worlds” (Letters and Journals 9: 46).

Discovering other worlds in the universe was, indeed, a religious concern. Some nineteenth-century astronomers argued that the expanded universe revealed by the telescope did not signal the obsolescence of religion but demanded a more expansive view of God. Thomas Dick (the Scottish minister and science teacher mentioned earlier) muses that it is “highly probable . . . that that portion of the universe which lies within the range of telescopic vision, and which contains so many millions of splendid suns and systems, is but a small part of the universal kingdom of Jehovah, compared with what lies beyond the utmost boundaries of human vision . . .” (284). For many, the telescope had a purpose that exceeded its empirical function: it liberated the imagination, enabling them to conceive of God in more expansive terms. Margaret Bryan, for example, declares, “most probably our system is composed of not one hundred-thousandth part of the whole creation; for, in the most crowded parts of the milky way, [Herschel] has seen 588 stars pass through the field of his large telescope in the space of one minute” (175). Earlier in her book she affirms, “God has created nothing in vain,” and later reasons that fixed stars, which have no use to Earth or other planets in our solar system, must serve other worlds (126, 169).

Herschel’s giant telescope, which caught the attention of scientists and lay people alike, had an aura even before its completion. During the construction of the telescope, the forty-foot tube, which was 15-1/3 feet in diameter, rested on the grass for a time. Caroline recalls in an 1840 letter to a niece: “Perhaps you may have heard that [on one occasion] in the early part of its existence, ‘God save the King’ was sung in it by the whole company, who got up from dinner and went into the tube . . .” (Mary Herschel 308). In a postscript to the letter, she writes: “Before the optical parts were finished, many visitors had the curiosity to walk through it, among the rest King George III., and the Archbishop of Canterbury, following the King, and finding it difficult to proceed, the King turned to give him the hand, saying, ‘Come, my Lord Bishop, I will show you the way to Heaven!’” (309). The king’s rapture was echoed by Herschel after the telescope was in use. In his paper “On the Power of Penetrating into Space by Telescopes,” he writes:

I remember, that after a considerable sweep with the 40 feet instrument, the appearance of Sirius announced itself, at a great distance, like the dawn of the morning, and came on by degrees, increasing in brightness, till this brilliant star at last entered the field of view of the telescope, with all the splendour of the rising sun, and forced me to take the eye from that beautiful sight. (54)

Though many swooned over the forty-footer, Herschel was not immune to criticism. In the January 1803 issue of the Edinburgh Review, a reviewer of his recently published papers writes: “Dr Herschel’s passion for coining words and idioms, has often struck us as a weakness wholly unworthy of him. The invention of a name is but a poor achievement for him who has discovered worlds. Why, for instance, do we hear him talking of the space-penetrating power of his instrument—a compound epithet and metaphor which he ought to have left to the poets, who, in some further ages, shall acquire glory by celebrating his name?” (qtd. in Lubbock 282). The reviewer’s concern with Herschel’s rhetoric is odd, but it does anticipate the legacy of the giant telescope. In step with the forty-footer, which penetrated space, Herschel’s coined phrase penetrated the public discourse and expanded the cultural imagination. A few years after the commentary in the Edinburgh Review, a harsh critique of the telescope came from the very astronomer who had proposed in 1781 that the newly discovered planet be named “Herschel.” Lalande, in his annual record of astronomical events for 1806, disparaged the forty-footer (Lubbock 313). Though Herschel’s brother Dietrich wrote a rebuttal, he was unable to point to any significant discoveries beyond the sighting of one of Saturn’s satellites (Lubbock 313-14).

In truth, the forty-footer did not deliver to the extent that Herschel himself had hoped it would. To perform a sweep of the skies required the telescope be moved, which was cumbersome and time-consuming to the point of hindering the sweeps. Several other factors, enumerated by Bennett, contributed to the limited value of the forty-foot instrument:

The limited zone [Herschel] could cover with the large instrument made a survey of the heavens quite impossible. . . . His other difficulties concerned the speculum. The thick mirror tarnished very quickly, a fact which is usually attributed to the large proportion of copper he used to increase its strength. Because of its size, it adjusted only slowly to changes in the surrounding temperature and so attracted much condensation, which accelerated the tarnishing. (92)

Along with the practical difficulties of operating the behemoth instrument and the tedium of its maintenance, it posed another problem: on at least one occasion it proved to be nearly lethal. In an 1807 diary entry, Caroline writes: “In taking the forty-foot mirror out of the tube, the beam to which the tackle is fixed broke in the middle, but fortunately not before it was nearly lowered into its carriage, &c., &c. Both my brothers had a narrow escape of being crushed to death” (Mary Herschel 113). But the inability of the forty-footer to fulfill the high expectations it inspired was largely due to Herschel’s own discoveries. Herschel had assumed a large telescope would be able to resolve nebulae into star clusters, but, as one biographer notes, “a year or so after its completion, Herschel recognized that many intractable nebulae are in fact gaseous and therefore, by their very nature, irresolvable” (Armitage 46).

In spite of its limitations as an instrument to advance understanding of the universe, as the largest telescope in the world, the forty-footer became an indelible image of human conquest. Oberamtmann Schroeter, an amateur German astronomer with whom Herschel corresponded for several years, articulated the symbolic value of the giant telescope in response to Herschel’s “Description of a Forty-feet Telescope”:

Your forty-foot Reflector is in truth a monument of astronomical and mechanical ingenuity. It shows how far human perseverance and zeal for the sublimest science can attain; though I am quite of your opinion that wide apertures do interfere with distinctness and that size renders the use of very large instruments more difficult and limited, yet in special cases, where increase of light is called for, they are of the greatest service, as your many important discoveries abundantly prove. (qtd. in Lubbock 215)

Late in his life Herschel, who was compelled to recognize the constraints of the giant instrument, advised his son John never to rebuild it (Bennett 101). This marked a precipitous change in his thinking since, in his 1795 description of the forty-footer, he lays out the nuts and bolts of how the giant instrument was constructed, suggesting that in the early days he saw the forty-footer as a model for future telescopes. As it happened, twenty years after Herschel published his manual on the forty-footer, the giant instrument was retired (Lubbock 342). Herschel, however, held onto the romance of his mechanical child. In less than a month before his passing, Caroline visited her brother, who was in very poor health. She notes in a diary entry that “as soon as he saw me I was sent to the Library to fetch one of his last papers and a Plate of the 40 feet telescope” (qtd. in Lubbock 360).

As a symbol, the giant telescope literally became imprinted in English culture when it was adopted as the official seal of the ![]() Royal Astronomical Society, an honor it retains to this day. As an instrument, it did not fare so well. Though Wordsworth underestimated the cultural power of the telescope, his image in “The Excursion” of one covered with cobwebs was prescient. In 1839, seventeen years after William Herschel’s death and nearly a quarter of a century after its final use, the Herschel family dismantled the forty-footer in a formal ceremony. William’s son John composed a requiem for the occasion, and, in what must have been a surreal moment, they sang the requiem from inside the giant tube (Lubbock 343). Free from the quotidian realm, their voices echoing back to themselves, the family could well have been singing a requiem to English Romanticism since only two years earlier, Victoria had begun her reign.

Royal Astronomical Society, an honor it retains to this day. As an instrument, it did not fare so well. Though Wordsworth underestimated the cultural power of the telescope, his image in “The Excursion” of one covered with cobwebs was prescient. In 1839, seventeen years after William Herschel’s death and nearly a quarter of a century after its final use, the Herschel family dismantled the forty-footer in a formal ceremony. William’s son John composed a requiem for the occasion, and, in what must have been a surreal moment, they sang the requiem from inside the giant tube (Lubbock 343). Free from the quotidian realm, their voices echoing back to themselves, the family could well have been singing a requiem to English Romanticism since only two years earlier, Victoria had begun her reign.

If one (fittingly) telescopes the lifespan of Herschel’s giant instrument, its historical moment is arresting. Six and a half weeks after the ![]() Bastille was razed to the ground, the forty-footer was raised to the heavens. If Herschel had had a stronger sense of history, he might have delayed the inauguration of his imposing instrument by a few months. (1789 would not be remembered as the year of the giant telescope.) The respective dates of the appearance and demise of the forty-footer, however, fortuitously frame the Romantic era. The heady, unbounded imagination with which the period has often been associated could hardly have a better symbol.

Bastille was razed to the ground, the forty-footer was raised to the heavens. If Herschel had had a stronger sense of history, he might have delayed the inauguration of his imposing instrument by a few months. (1789 would not be remembered as the year of the giant telescope.) The respective dates of the appearance and demise of the forty-footer, however, fortuitously frame the Romantic era. The heady, unbounded imagination with which the period has often been associated could hardly have a better symbol.

In that regard, one more dimension of the telescope’s cultural reach deserves mention. Though John Keats does not refer to Herschel’s forty-footer, he does allude to his discovery of Uranus in his sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.”[7] In a description of the exhilaration of navigating Chapman’s translation of Homer, Keats writes:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific — and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise —

Silent, upon a peak in Darien. (9-14)

Keats’s linking of cosmic exploration to the conquest of other lands exemplifies how in the European imagination, the telescope, aimed vertically at the cosmic unknown, was repositioned and directed horizontally into unknown regions of the earth. To Keats and his contemporaries, the darker side of conquest was often overlooked, however, and in 1811, when Herschel’s forty-footer was still in active use, John Bonnycastle, a professor of mathematics, offered a sublime defense for such cosmic instruments, intimating their ability to transform humanity. His words cogently describe the telescope of the imagination, an ideal to which Herschel’s colossal instrument could only aspire: “The progress of reason, and the powers of the imagination, are almost without bounds; and if we add to these, the invention of instruments, which are so many new organs of power and perception, man becomes a being worthy of admiration. . . . [He] creates to himself a new being . . .” (242).

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published July 2012

Lundeen, Kathleen. “On Herschel’s Forty-Foot Telescope, 1789.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Armitage, Angus. William Herschel. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd., 1963. Print.

Bennett, J. A. “`On the Power of Penetrating into Space’: The Telescopes of William

Herschel.” Journal for the History of Astronomy 7 (1976): 75-108. Print.

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry & Prose. Newly rev. ed. Ed. David V. Erdman. New York: Doubleday, 1988. Print.

—. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. The Complete Poetry & Prose. Newly rev. ed. Ed. David V. Erdman. New York: Doubleday, 1988. 33-45. Print.

—. Milton: a Poem in 2 Books. The Complete Poetry & Prose. Newly rev. ed. Ed. David V. Erdman. New York: Doubleday, 1988. 95-144. Print.

Bonnycastle, John. An Introduction to Astronomy in a Series of Letters, from a Preceptor to His Pupil, in which the Most Useful and Interesting Parts of the Science are Clearly and Familiarly Explained. 6th ed. London: Printed for J. Johnson and Co., St. Paul’s Church-yard, 1811. Print.

Bryan, Margaret. A Compendious System of Astronomy, in a Course of Familiar Lectures, in which the Principles of that Science Are Clearly Elucidated, so as to Be Intelligible to those Who Have Not Studied the Mathematics; also Trigonometrical and Celestial Problems, with a Key to the Ephemeris, and a Vocabulary of the Terms of Science Used in the Lectures. 3rd ed. London: C. and W. Galabin, Ingram-Court, Fenchurch-Street, 1805. Print.

Byron, Lord. “Darkness.” The Complete Poetical Works. Ed. Jerome J. McGann. Vol. 4. Oxford: Clarendon, 1986. 40-43. Print.

—. “The Dream.” The Complete Poetical Works. Ed. Jerome J. McGann. Vol. 4. Oxford: Clarendon, 1986. 22-29. Print.

—. “Heaven and Earth.” The Complete Poetical Works. Eds. Jerome J. McGann and Barry Weller. Vol. 6. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991. 346-381. Print.

—. Letters and Journals. Ed. Leslie A. Marchand. Vols. 3, 9. London: John Murray, 1979. Print.

—. Manfred. The Complete Poetical Works. Ed. Jerome J. McGann. Vol. 4. Oxford: Clarendon, 1986. 51-102. Print.

—. “The Vision of Judgment.” The Complete Poetical Works. Eds. Jerome J. McGann and Barry Weller. Vol. 6. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991. 309-345. Print.

Clerke, Agnes M. The Herschels and Modern Astronomy. London: Cassell and Co., 1901. Print.

Dick, Thomas, LL. D. The Sidereal Heavens and Other Subjects Connected With Astronomy, as Illustrative of the Character of the Deity, and of an Infinity of Worlds. 1840. New York: Harper & Brothers, Franklin Square, 1872. Print.

Erdman, David V. “Preface.” The Complete Poetry & Prose. Newly rev. ed. By William Blake. New York: Doubleday, 1988. xxiii-xxiv. Print.

Gaull, Marilyn. “Under Romantic Skies: Astronomy and the Poets.” The Wordsworth Circle 21.1 (1990): 34-41. Print.

Henchman, Anna. “The Telescope as Prosthesis.” Victorian Review: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Victorian Studies 35.2 (2009): 23-27. Print.

Herschel, Mary. Memoir and Correspondence of Caroline Herschel. 1876. Ed. Mary Herschel. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010. Print.

Herschel, William, LL. D. F. R. S. “Description of a Forty-Feet Reflecting Telescope.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 85 (1795): 347-409. Jstor. Web. 10 June 2012.

—. “On the Power of Penetrating into Space by Telescopes; with a Comparative Determination of the Extent of that Power in Natural Vision, and in Telescopes of Various Sizes and Constructions; Illustrated by Select Observations.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 90 (1800): 49-85. Jstor. Web. 10 June 2012.

—. The Scientific Papers, Including Early Papers Hitherto Unpublished. Ed. Royal Society and Royal Astronomical Society. 2 vols. London: The Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society, 1912. Print.

Keats, John. “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.” Complete Poems. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1982. 34. Print.

King James Version of the Holy Bible. New York: Penguin, 1974. Print.

Lardner, Dionysius, Rev. LL.D. F.R.S. L. and E. A Discourse on the Advantages of Natural Philosophy and Astronomy, as Part of a General and Professional Education. London: Printed for John Taylor, bookseller and publisher to the University of London, 30, Upper Gower Street, 1829. Print.

Lubbock, Constance A. The Herschel Chronicle: The Life-Story of William Herschel and His Sister Caroline Herschel. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1933. Print.

Lundeen, Kathleen. “A Wrinkle in Space: The Romantic Disruption of the English Cosmos.” Pacific Coast Philology 43 (2008): 1-19. Print.

Lussier, Mark. “Scientific Objects and Blake’s Objections to Science.” The Wordsworth Circle 39.3 (2008): 120-22. Print.

Owens, Thomas. “Astronomy at Stowey: The Wordsworths and Coleridge.” The Wordsworth Circle 43.1 (2012): 25-29. Print.

Roe, Nicholas. John Keats and the Culture of Dissent. Oxford: Clarendon, 1997. Print.

Ross, Catherine E. “‘Twin Labourers and Heirs of the Same Hopes’: The Professional Rivalry of Humphry Davy and William Wordsworth.” Romantic Science: The Literary Forms of Natural History. Ed. Noah Heringman. Albany: SUNY P, 2003. 23-52. Print.

Sidgwick, J. B. William Herschel: Explorer of the Heavens. London: Faber and Faber, 1954. Print.

Wordsworth, William. The Excursion, Book II. Poetical Works. Eds. E. De Selincourt and Helen Darbishire. Vol. 5. 1949. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1959. 41-74. Print.

—. “If Thou Indeed Derive Thy Light from Heaven.” Selected Poems and Prefaces. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965. 434. Print.

—. The Prelude. Selected Poems and Prefaces. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965. 193-366. Print.

—. Selected Poems and Prefaces. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965. Print.

—. “Star-Gazers.” Selected Poems and Prefaces. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965. 371-72. Print.

—. “The Thorn.” Selected Poems and Prefaces. Ed. Jack Stillinger. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965. 70-76. Print.

WORKS CITED

[1] Dick notes, “The lustre and brilliancy which the fixed stars exhibit when viewed with telescopes of large apertures and powers is exceedingly striking. Sir W. Herschel seldom looked at the larger stars through his forty-feet telescope, because their blaze was injurious to his sight” (230).

[2] Among the many scholars who have pursued Wordsworth’s forays into science is Catherine Ross, who has documented the professional rivalry between Wordsworth and Humphry Davy in her essay “‘Twin Labourers and Heirs of the Same Hopes.’”

[3] I have preserved Blake’s unorthodox spelling and punctuation, and David Erdman’s symbols. Erdman explains, “Angle brackets <thus> enclose words or letters written to replace deletions, or as additions, not including words written immediately following and in the same ink or pencil as deleted matter” (xxiv).

[4] In a letter of 1795, Blake scorns “the pretended Philosophy which teaches that Execution is the power of One & Invention of Another” (699). He goes on to say, “he who can Invent can Execute,” and, indeed, in his illuminated poetry he performs both functions.

[5] The writer of I Samuel notes, “[For] he that is now called a Prophet was beforetime called a Seer” (King James Bible 9.9)—a definition of “prophet,” incidentally, that Blake adopts. In his “Annotations to An Apology for the Bible,” Blake notes, “a Prophet is a Seer not an Arbitrary Dictator” (617).

[6] In my article “A Wrinkle in Space,” I argue that Blake presents science as the art of improvisation (16).

[7] Though Keats received a copy of John Bonnycastle’s Introduction to Astronomy as a prize, Nicholas Roe has argued, “It seems unlikely that the desiccated prose of [Bonnycastle’s book] should have quickened the marvellous vision of sidereal motion in Keats’s’ poem. More plausible, I think, is the possibility that Keats’s imagination was feeding on the memory of discoveries made at Enfield while playing in the ‘living orrery’ or gazing at a planet’s bright image through the school telescope” (37). Though Keats’s early adventures in astronomy no doubt sparked an interest in cosmic exploration, Bonnycastle’s book includes some sublime passages, one of which I quote in this essay, and he may deserve some credit for firing up Keats’s imagination.