Abstract

This essay considers the significance of one of the signal technological developments of the nineteenth century—an event so signal that it happened twice. The transatlantic telegraph cable linking the Old World with the New was first successfully completed in August 1858, only to cease functioning within a month, and was permanently re-established in July, 1866, this time accompanied by the reappearance, with slight variations, of much of the verse and prose written to commemorate the original success, in what might be considered a case of canny cultural recycling. While the cable ultimately connected England and the United States, it only did so by way of Ireland and Canada, which is to say that this was very much an imperial project, one celebrated as reinforcing transatlantic ethnic and linguistic superiority in a mythology of Anglo-Saxonism that Victorians largely constructed and widely endorsed. As a way to approach this convergence of ideologies of progress, empire, language, and race, the essay focuses on what arguably was the critical aspect of the cable’s material composition, and considers, in general terms and in the specific literary case of Henry James, how the concept of insulation can help us to interpret representations of the cable and the transatlantic ties it extended.

Safe & well expect good letter full of Hope

Charles Dickens to W. H. Wills, 22 November 1867

(Dickens Letters 11:487)

Charles Dickens telegraphed the above message to W. H. Wills, his acting editor for All the Year Round, from ![]() Boston as he began his second American reading tour. Wills was what Dickens called his “factotum,” or all-purpose assistant, in his personal as well as professional life, and the acting editor knew that his boss was speaking, or signalling, in code. A surviving scrawl in a diary reveals that weeks before Dickens left on his transatlantic journey, he had indicated that he would cable one of two telegrams to Wills upon arrival: “all well” if conditions were such that it would be possible to have his mistress Ellen Ternan, whom he referred to in letters as “the patient,” sent inconspicuously to accompany him on the trip, or “safe and well” if they were not.[1] As the epigraph indicates, Dickens, by this time an international celebrity whose every move in the United States was tracked by the press, belatedly came to his senses, and, with Wills’s assistance—or it might be more accurate to say without it—Ellen Ternan remained in England.

Boston as he began his second American reading tour. Wills was what Dickens called his “factotum,” or all-purpose assistant, in his personal as well as professional life, and the acting editor knew that his boss was speaking, or signalling, in code. A surviving scrawl in a diary reveals that weeks before Dickens left on his transatlantic journey, he had indicated that he would cable one of two telegrams to Wills upon arrival: “all well” if conditions were such that it would be possible to have his mistress Ellen Ternan, whom he referred to in letters as “the patient,” sent inconspicuously to accompany him on the trip, or “safe and well” if they were not.[1] As the epigraph indicates, Dickens, by this time an international celebrity whose every move in the United States was tracked by the press, belatedly came to his senses, and, with Wills’s assistance—or it might be more accurate to say without it—Ellen Ternan remained in England.

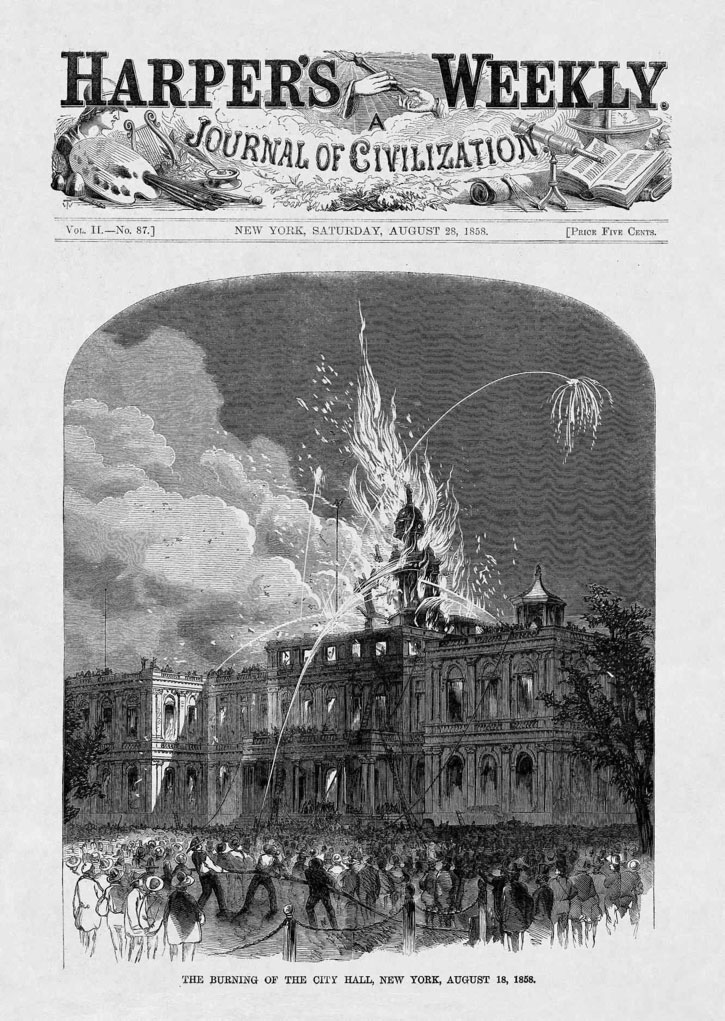

Dickens’s brief flirtation with the telegraph for romantic purposes at this historical moment draws attention to the then-current technological development that allowed him to communicate with such speed about the fate of his mistress in the first place. Just a year earlier, in 1866, Cyrus Field and the crew of the Great Eastern finally completed the laying of the Atlantic cable connecting the Old World with the New. Telegraphy and telegraph cables were familiar facts of life, of course, as Victorians by then had witnessed about three decades of the accelerating growth of electric wires and poles across their landscape. But the cable across the ocean was a new phenomenon altogether, in scope, in cost, in effort, and as a spark for what might be called the Victorian material imagination, the endearing but often just weird mix of fantasy and propaganda that resulted from fetishizing products of industrialized commerce. Others have told the story, beginning in the 1840s, of the initial ideas for, Field’s financing of, and the failed attempts and ultimately successful laying of the Atlantic cable, and the trial and error behind the construction and powering of it. The key dates are August 1858, when, to riotous celebrations in the United States, in which fireworks destroyed the cupola of ![]() New York’s City Hall (see Fig. 1), the first cable was successfully completed between

New York’s City Hall (see Fig. 1), the first cable was successfully completed between ![]() Valentia, Ireland and

Valentia, Ireland and ![]() Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, only to cease functioning within a month, and July 1866, in the aftermath of the Civil War, when a permanent connection was finally re-established. This repetition of events was accompanied by the reappearance, with slight variations, of much of the verse and prose written to commemorate the 1858 success, in what might be considered a case of canny cultural recycling.

Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, only to cease functioning within a month, and July 1866, in the aftermath of the Civil War, when a permanent connection was finally re-established. This repetition of events was accompanied by the reappearance, with slight variations, of much of the verse and prose written to commemorate the 1858 success, in what might be considered a case of canny cultural recycling.

It is worth noting that while the cable ultimately connected England and the United States, it only did so by way of ![]() Ireland and

Ireland and ![]() Canada, which is to say that this was very much an imperial project, one celebrated as reinforcing transatlantic ethnic and linguistic superiority in a mythology that Victorians largely constructed and widely endorsed. The Atlantic cable story as it appears in conventional recent accounts, which in their triumphalism take their cue from the initial contemporary panegyrics, is one that pits American and British grit, capital, and technological ingenuity against more primal forces of nature and distance. A more fundamental symbolic underpinning to the project was racial: that the completion of the cable would help bring about, as Cyrus Field pitched it to his potential investors, “the unity of the ‘Anglo-Saxon race.’” Or, as another prospectus put it, “The Anglo-Saxon race, which is in the van of all social progress, dwells on both sides of the Atlantic,” so it was only logical, in the name of progress, to link those sides (Coates and Finn 8; [Mann] 6). Moreover, while the Atlantic cable could serve to confirm the global ascendency of the “Anglo-Saxon” tongue by virtue of its status as a medium for communication in English, a certain irony resided in the tendency of telegraphese to defy grammar and structural conventions at the risk of provoking ambiguity, and even, on occasion, incomprehension. As a way to approach this convergence of Victorian ideologies of progress, empire, language, and race, I focus on what arguably was the critical aspect of the cable’s material composition, its insulation, and consider, first in general terms and second in a particular literary case, how this approach can influence the ways we interpret representations of the cable and the transatlantic connection it engendered.

Canada, which is to say that this was very much an imperial project, one celebrated as reinforcing transatlantic ethnic and linguistic superiority in a mythology that Victorians largely constructed and widely endorsed. The Atlantic cable story as it appears in conventional recent accounts, which in their triumphalism take their cue from the initial contemporary panegyrics, is one that pits American and British grit, capital, and technological ingenuity against more primal forces of nature and distance. A more fundamental symbolic underpinning to the project was racial: that the completion of the cable would help bring about, as Cyrus Field pitched it to his potential investors, “the unity of the ‘Anglo-Saxon race.’” Or, as another prospectus put it, “The Anglo-Saxon race, which is in the van of all social progress, dwells on both sides of the Atlantic,” so it was only logical, in the name of progress, to link those sides (Coates and Finn 8; [Mann] 6). Moreover, while the Atlantic cable could serve to confirm the global ascendency of the “Anglo-Saxon” tongue by virtue of its status as a medium for communication in English, a certain irony resided in the tendency of telegraphese to defy grammar and structural conventions at the risk of provoking ambiguity, and even, on occasion, incomprehension. As a way to approach this convergence of Victorian ideologies of progress, empire, language, and race, I focus on what arguably was the critical aspect of the cable’s material composition, its insulation, and consider, first in general terms and second in a particular literary case, how this approach can influence the ways we interpret representations of the cable and the transatlantic connection it engendered.

The core of the Atlantic cable featured two essential components that had constituted the basic elements of submarine telegraph cables since the first was successfully laid across ![]() the English Channel in 1850: a wire conductor of copper and an insulator, or “insulating envelope” as it was sometimes called, of gutta percha, the textile found to be best suited to protecting the conductivity of the copper and ensuring the efficacy of submarine telegraphy. Gutta percha, a Malaysian tree gum, had been introduced to England by William Montgomerie, a surgeon in the East India Company, who in 1843 sent specimens of it to the Society of Arts.[2] In Prussia in 1846, Werner Siemens discovered that gutta percha, which could be easily manipulated in hot water and hold that shape at colder temperatures, made an excellent insulator for underground telegraph wires. In 1847, he invented a machine to coat wires with it, and in 1848 he conducted trials of gutta percha-coated wires in underwater telegraphy.[3] Gutta percha was identified as a “miracle substance, just in time for its God-appointed use” as insulation material (Finn 12). In addition to widespread use in ear trumpets and speaking tubes, in surgery, and in dentistry (where even today it features in root canals), gutta percha quickly became the Victorian telegraph insulator par excellence, not only for the failed first version of the Atlantic cable in 1857–58 but also for the later two versions in 1865–66. These three attempts alone consumed a total “insulating envelope” of over nine hundred tons of gutta percha.[4]

the English Channel in 1850: a wire conductor of copper and an insulator, or “insulating envelope” as it was sometimes called, of gutta percha, the textile found to be best suited to protecting the conductivity of the copper and ensuring the efficacy of submarine telegraphy. Gutta percha, a Malaysian tree gum, had been introduced to England by William Montgomerie, a surgeon in the East India Company, who in 1843 sent specimens of it to the Society of Arts.[2] In Prussia in 1846, Werner Siemens discovered that gutta percha, which could be easily manipulated in hot water and hold that shape at colder temperatures, made an excellent insulator for underground telegraph wires. In 1847, he invented a machine to coat wires with it, and in 1848 he conducted trials of gutta percha-coated wires in underwater telegraphy.[3] Gutta percha was identified as a “miracle substance, just in time for its God-appointed use” as insulation material (Finn 12). In addition to widespread use in ear trumpets and speaking tubes, in surgery, and in dentistry (where even today it features in root canals), gutta percha quickly became the Victorian telegraph insulator par excellence, not only for the failed first version of the Atlantic cable in 1857–58 but also for the later two versions in 1865–66. These three attempts alone consumed a total “insulating envelope” of over nine hundred tons of gutta percha.[4]

The Malay Archipelago was the only source for suitable gutta percha, and the enormous demand provoked unregulated tree removal, leading to what now would be identified as an environmental disaster. Entire forests were decimated to make enough insulation for Victorian cables.[5] In the words of one writer reflecting on the diminished supply in 1898,

As soon as the valuable properties of gutta percha had been recognised in Europe and a demand had been created for the article, the countries all around

Singapore were searched with great avidity for Taban trees, and almost a craze for getah-collecting sprang up among the indigenous population. . . . An immense number of trees of great size and age, probably hundreds of thousands, were ruthlessly destroyed during the first four or five years, and whole forests denuded of them, like those on Singapore. (Obach 12)

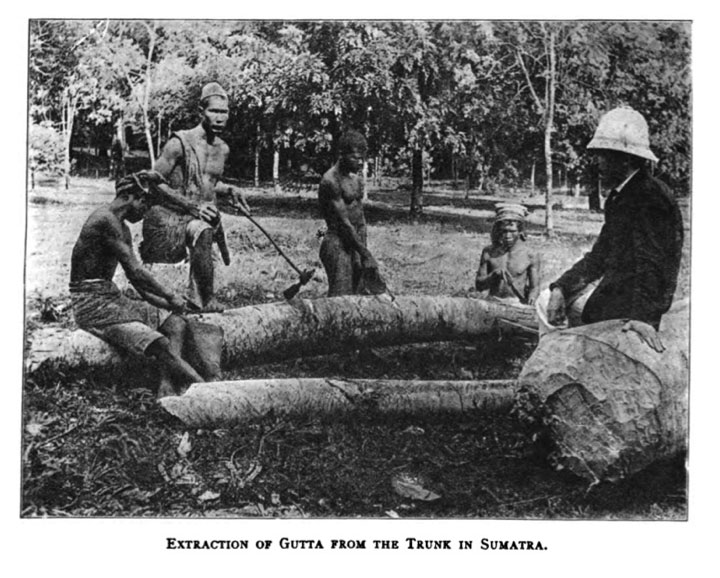

Or, as Charles Bright, the electrical engineer who oversaw the laying of the cable, put it, “The felling of the trees has been carried out in such a ruthless manner that an adult specimen is now rarely seen, and in ![]() Sumatra, the gutta-seekers themselves cannot recognize either the flowers or the seeds by sight.” Bright wrote that “ruthless destruction by the natives” had “exhausted” Singapore’s gutta resources and that, in order to maximize profit from the sale of other varieties by weight, “the noble but enterprising savage” was injecting “impurities” into them (Bright 254, 256, 285). Bright insinuated that the environmental devastation and economic consequences were the fault of the colonized while neglecting to point out that it was the Westerners whose insatiable desire for technological “progress,” after all, had led to such ruthless consumption of telegraphic insulation in the first place (see Fig. 2).[6] As Daniel Headrick has put it in a discussion of the rise and fall of the international market for gutta percha, “Western people, then as now, waxed indignant about the evil side effects of the plunder of the world’s resources, while enjoying its fruits” (13).

Sumatra, the gutta-seekers themselves cannot recognize either the flowers or the seeds by sight.” Bright wrote that “ruthless destruction by the natives” had “exhausted” Singapore’s gutta resources and that, in order to maximize profit from the sale of other varieties by weight, “the noble but enterprising savage” was injecting “impurities” into them (Bright 254, 256, 285). Bright insinuated that the environmental devastation and economic consequences were the fault of the colonized while neglecting to point out that it was the Westerners whose insatiable desire for technological “progress,” after all, had led to such ruthless consumption of telegraphic insulation in the first place (see Fig. 2).[6] As Daniel Headrick has put it in a discussion of the rise and fall of the international market for gutta percha, “Western people, then as now, waxed indignant about the evil side effects of the plunder of the world’s resources, while enjoying its fruits” (13).

Figure 2: From Eugene F. A. Obach, _Cantor Lectures on Gutta Percha_ (London: William Trounce, 1898)

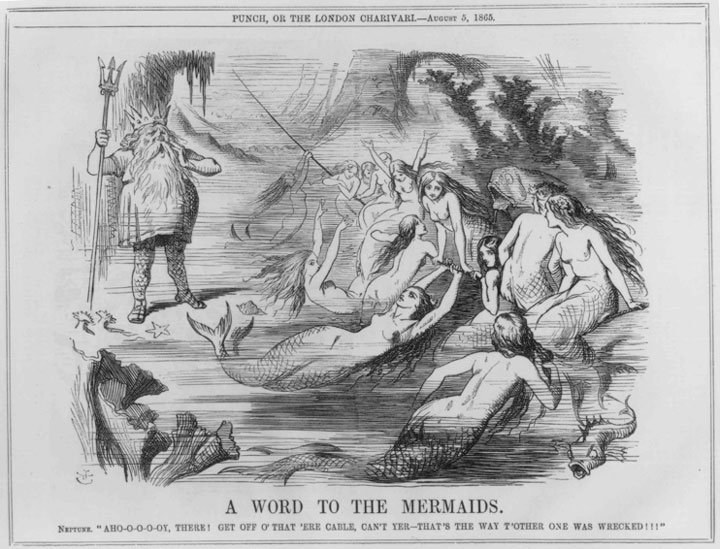

Looked at from a broader perspective, the colonial economy literally insulated the objects of Victorian progress even as Victorians remained largely undeterred by, if not resigned to or even insulated from, the exploitative realities and unintended environmental consequences of this progress. This, in itself, should not come as a surprise, but it is curious to consider the ways in which depictions of the submerged electric cable came to be charged with distinctly Victorian kinds of tension, as Victorians sublimated their own perhaps unconscious awareness of the material and moral costs of progress into representations that suggested, on the one hand, marital and sexual tensions—the tension between two bodies—and on the other, the repressed tensions over matters of cultural survival. In part, what I want to suggest is that the exotic, colonial, and environmental concerns that were woven into the very fabric of the cable surfaced in the more familiar telegraphic milieu of flirtatious communications and “wired love.”[7] Popular journalism set the conventional tone with portrayals of the cable that appealed to Victorian notions of marital bliss. “The Atlantic Wedding-Ring,” a poem by George Wilson published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, associated the “Fatherland” with “the Bridegroom,” and “Daughter” America with the “willing Bride,” while a writer for Punch commented that “the Sub-Atlantic wire is the wedding-ring which joins” America and England, and concluded by referencing the recently passed Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act as well as the welding of the wires in the middle of the ocean during the first attempt: “May no divorce act ever separate those who’re now united by the Sub-Atlantic splice!” (Wilson 458; “‘Nearer and Dearer’” 73). The electric marriage was already on the rocks—the 1858 cable, as we know, went on to fail within a month. Punch was one of several magazines to publish cartoons over the years that portrayed the Atlantic cable, and submarine cables more generally, as connections between men and women (or sometimes between two women or two men) standing in for their respective nations (“John Bull” and “Jonathan,” for example). But alongside these typically staid cartoons, there are others such as John Tenniel’s “big cut” from an August 1865 issue (Fig. 3). In what would appear to be a harmless fantasy scene, a Mr. Punch-like Neptune scolds frolicking mermaids to “get off o’that ’ere cable, can’t yer—That’s the way t’other one was wrecked!!!” The illustration’s theme of tension—that is, the added tension that presumably will snap the strained cable—is reinforced by the odd sexual tension of the mermaids’ remarkably exhibitionistic underwater gymnastics. The uncharted, mysterious ocean depths provide a perfect blank space for the artist to fill in and flesh out with both his imagination and, not entirely distinct from this, what we might call a cultural unconscious. Tenniel’s “big cut” about the fear of a big break submerges and channels the unresolved tensions (colonial and environmental, to name two) of the cable saga into an example of what could pass for Punch pornography. The mermaids constitute the literal and figurative threat to the very marriage between nations that Punch earlier had welcomed.

*

I shall be home to dinner. Keep the American.

Telegram in Henry James’s “A Passionate Pilgrim” (1871)

(Complete Stories 1864-1874 575)

To move from this overview to a consideration (albeit brief) of a distinct literary case: for Henry James, conventional deployments of the telegraph and telegram give way to more charged depictions of transatlantic telegraphy that suggest the discord beneath the comity the Atlantic cable was supposed to confirm. I am hardly the first to note the omnipresence of telegraphy in James’s fiction. His 1898 novella In the Cage, which has experienced a resurgence of critical attention with the advent of the internet, goes so far as to take telegraphy as its central metaphor and the “telegraph girl,” the woman “in the cage,” as its protagonist. Long before In the Cage, however—as far back as the central period in this essay, the decade of the Atlantic cable, which included the publication of “The Story of a Year,” James’s first signed story in 1865—telegraphy, specifically, telegrams were making their way into his works. In the case of the Civil War tale “The Story of a Year,” a telegram stating that “Lieutenant Ford dangerously wounded in the action of yesterday. You had better come on” arrives for Mrs. Ford (CS 1864-1874 47). In “A Light Man” from 1869, telegrams are sent regarding a death, while “A Passionate Pilgrim” features a telegram (noted in the above epigraph) composed “with something certainly of telegraphic curtness” (575). The novella-length “Guest’s Confession” (1872) opens with a note, “Arrive at half past eight. Sick. Meet me,” written with “telegrammatic brevity” (669).

There are references to telegraphic messages in Watch and Ward (1870), James’s first novel, as well as Roderick Hudson (1875). Specifically transatlantic cables enter the James canon with The American (1876-1877), which features the word “telegram” and a transatlantic message when the American businessman Christopher Newman sends word of his betrothal to a Parisian aristocrat back to the States. In “An International Episode” (1878-1879), Lord Lambeth receives a telegram from his mother “requesting him to return immediately to England; his father had been taken ill, and it was his filial duty to come to him” (Complete Stories 1874-1884 360). And “A Bundle of Letters,” from 1879, features a telegram sent from New York to Paris telling Miss Violet Ray’s father to return for business reasons. These appearances of telegraphy in James’s apprentice or early works are rather typical uses of the telegram for matters of life, death, marriage, business, or some combination of the above, even as his expanse widens to include continental dispatches. But with The Portrait of a Lady (1880-1881), the greatest novel of his early period, James would find a way to make the (transatlantic) telegraphic form and its medium function symbolically; we might even say he determines to ascribe it an aesthetic, a version of what Richard Menke has called “telegraphic realism.”[8]

We have already seen how the Atlantic cable put Dickens in mind not of his wife but of his mistress, with a telegram sent in insulating code. As if in distant response to Dickens, consider the opening of The Portrait, set about three years after Dickens sent his underwater message. Here, James offers his own perspective on those dynamics with a different marital study centered on Isabel Archer. Tellingly, she enters the novel as a character in someone else’s text, a telegram sent from America to England by Mrs. Touchett, her aunt, and a woman herself involved in a difficult marriage: “Changed hotel, very bad, impudent clerk, address here. Taken sister’s girl, died last year, go to Europe, two sisters, quite independent” (Portrait 67). The oblique reference and confused syntax of the message, noted within the text, leave ambiguous not only whose position is “quite independent” but even, with “died last year,” Isabel’s status as living and vital. So too does the novel, with the story of her disastrous marriage to Gilbert Osmond. In The Portrait, the Atlantic cable is no longer—if it ever was—a “great peace-maker,” as one poet had put it, but in its own disjointed way conveys a distant portent of marital strife.[9] By the end of the novel, Isabel will be left disillusioned if not broken, deprived of a form of insulation that is scarce enough, her innocence.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published January 2013

Picker, John M. “Threads across the Ocean: The Transatlantic Telegraph Cable, July 1858, August 1866.”BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Bright, Charles. Submarine Telegraphs: Their History, Construction, and Working. London: Crosby Lockwood, 1898. Print.

Coates, Vary T. and Bernard Finn. A Retrospective Technology Assessment: Submarine Telegraphy. The Transatlantic Cable of 1866. San Francisco: San Francisco Press, 1979. Print.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey. Vol. 11. Oxford: Clarendon, 1999. Print.

Finn, Bernard. “Submarine Telegraphy: A Study in Technical Stagnation.” 9-24 in Communication Under the Seas: The Evolving Cable Network and Its Implications. Ed. Bernard Finn and Daqing Yang. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009. Print.

Freedgood, Elaine. The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2006. Print.

Goble, Mark. “Wired Love: Pleasure at a Distance in Henry James and Others,” ELH 74 (2007): 397-427. Print.

Headrick, Daniel R. “Gutta-Percha: A Case of Resource Depletion and International Rivalry.” IEEE Technology and Society Magazine 6.4 (1987): 12-16. Print.

[Horne, R. H.]. “The Great Peace-Maker.” Household Words 3 (1851): 275-77. Print.

Horne, R. H. The Great Peace-Maker: A Sub-Marine Dialogue. London: Sampson Low, 1872. Print.

James, Henry. Complete Stories 1864-1874. New York: Library of America, 1999. Print.

—. Complete Stories 1874-1884. New York: Library of America, 1999. Print.

—. The Portrait of a Lady. Ed. Geoffrey Moore. London: Penguin, 2003. Print.

[Mann, R. J.]. The Atlantic Telegraph: A History of Preliminary Experimental Proceedings, and a Descriptive Account of the Present State & Prospects of the Undertaking. London: Jarrold and Sons, 1857. Print.

Menke, Richard. Telegraphic Realism. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2008. Print.

“‘Nearer and Dearer.’—The Subatlantic Splice.” Punch 35 (1858): 73. Print.

Obach, Eugene F. A. Cantor Lectures on Gutta Percha. London: William Trounce, 1898. Print.

Otis, Laura. Networking: Communicating with Bodies and Machines in the Nineteenth Century. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2001. Print.

Stubbs, Katherine. “Telegraphy’s Corporeal Fictions.” New Media, 1740-1915. Ed. Lisa Gitelman and Geoffrey B. Pingree. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003. 91-111. Print.

Thayer, Ella Cheever. Wired Love: A Romance of Dots and Dashes. New York: W. J. Johnston, 1880. Print.

Tomalin, Claire. The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens. New York: Knopf, 1991. Print.

Wilson, George. “The Atlantic Wedding-Ring.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 84 (1858): 458. Print.

ENDNOTES

This essay is an expanded version of one that appeared in Victorian Review 34.1 (2008): 34-38. I address the concerns of this piece at much greater length in an unpublished essay, “Reading the Atlantic Cable,” part of a work-in-progress material history of the intersections among literature, culture,

and media from the 1850s through the 1950s.

[1] For a fuller explanation of the telegram and Dickens’s code, see Tomalin 179–81.

[2] Information about gutta percha in this paragraph comes from Bright, Submarine Telegraphs.

[3] For more on Siemens’s role in this discovery, see Otis, Networking 132–33.

[4] This figure is from the chart in Appendix 10 of Obach, Cantor Lectures 102.

[5] I am indebted to Elaine Freedgood’s work on Victorian thing theory for helping me to think through the literal and symbolic significance of the cable. See her The Ideas in Things, especially her discussion of mahogany, deforestation, and Jane Eyre (30–54).

[6] As costs of gutta percha escalated, Europeans realized the need for the reforestation of guttifers and attempted limited cultivation of them in the 1880s. Bright writes that “it is to be sincerely hoped. . . that electrical industries may not suffer from scarcity of this almost indispensable substance” (259).

[7] Wired Love, Ella Cheever Thayer’s 1880 novel about a budding romance between two telegraphers, has been much discussed in recent criticism about the relationship between telegraphy and literature, as for example in Otis, 147–162, as well as Stubbs, 99-103. See also Goble.

[8] Although Menke’s discussion of James centers around In the Cage, mention is made of some of the earlier novels’ references to telegrams: James uses the telegrams of The Portrait “to convey not only the character’s personal style but also many of the novel’s central issues” (195-96).

[9] In 1851, R. H. Horne published “The Great Peace-Maker” in Household Words in the context of the then new ![]() Dover-Calais cable. The poem was published in different form in a book in 1872, with an introduction that argued for its applicability to the Atlantic cable as well.

Dover-Calais cable. The poem was published in different form in a book in 1872, with an introduction that argued for its applicability to the Atlantic cable as well.