Abstract

This entry looks at how, in the aftermath of Oscar Wilde’s death, those individuals closest to the writer sought a suitable funerary monument in memorial. I first explore the interpersonal and aesthetic politics that informed the choice of Jacob Epstein as the tomb’s commissioned sculptor, and how that choice must be understood as integral to how we remember Wilde today. Noting how profoundly the aesthetics of funerary sculpture are in dialogue with both literary and queer history, this essay also briefly imagines how an alternate monument adorning Wilde’s tomb might have differently configured that dialogue. By comparing Epstein’s tomb with the radically different aesthetics that guide a “rejected” design, this one by the writer’s close artistic collaborator and friend Charles Ricketts, this essay considers how aesthetics have shaped twentieth and twenty-first century approaches to queer memory, mourning, and modernity.

Figure 2: Charles Ricketts, Silence (a memorial to Wilde), 1905. Courtesy of the William Andrews Clark Library, UCLA.

At the start of November 1900, an already-ill Oscar Wilde brushed off with characteristic wit and prescience a friend’s warning that if he did not “pull himself up” he would not live much longer: “He of course laughed,” recounted Wilde’s literary executor and one-time lover Robert Ross, “and said he could never outlive the century as the English people would not stand it” (“To Adela Schuster” 1227). True to prediction, the Irish writer succumbed to complications from cerebral meningitis only three weeks later, on 30 November, at the age of 46. Wilde’s death preceded that of Queen Victoria by less than two months. Consequently, at the start of 1901, the explosive case of Regina v. Wilde (1895) might have reasonably been considered at long last closed—firmly consigned to the nineteenth century by the passing of its two central adversaries. Yet the fallout from Wilde’s trials, imprisonment, and early death-in-exile extended far into the twentieth century. The earliest manifestation of this battle over Wilde’s place in the new century played out through heated debates over how the writer should be honored and remembered through funerary monument.

Wilde’s tomb at ![]() Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, is a living place; controversy still swirls around its conception, installation, suppression, desecration, veneration and, most recently, sanitization. The history of this tomb highlights changing attitudes towards queer memorial practices over the course of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Jacob Epstein’s monument to Wilde has elicited veneration and condemnation in equal measure since being transported in 1912 from the artist’s London studio to its final resting place (Fig. 1). Even today, this twenty-ton block of English stone—carved and chiseled into a strikingly stylized art-deco variation on a fantastical, male Sphinx—stands out like a sore thumb in a nineteenth-century cemetery whose sculptural aesthetic seems, to the modern visitor, overarchingly figurative and representational. It is precisely this aesthetic alterity that has, for one hundred years, prompted viewers to regard Epstein’s “Tomb for Oscar Wilde” as future- rather than past-oriented, more modernist than Victorian, a monument to enlightened pride rather than retrograde shame.

Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, is a living place; controversy still swirls around its conception, installation, suppression, desecration, veneration and, most recently, sanitization. The history of this tomb highlights changing attitudes towards queer memorial practices over the course of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. Jacob Epstein’s monument to Wilde has elicited veneration and condemnation in equal measure since being transported in 1912 from the artist’s London studio to its final resting place (Fig. 1). Even today, this twenty-ton block of English stone—carved and chiseled into a strikingly stylized art-deco variation on a fantastical, male Sphinx—stands out like a sore thumb in a nineteenth-century cemetery whose sculptural aesthetic seems, to the modern visitor, overarchingly figurative and representational. It is precisely this aesthetic alterity that has, for one hundred years, prompted viewers to regard Epstein’s “Tomb for Oscar Wilde” as future- rather than past-oriented, more modernist than Victorian, a monument to enlightened pride rather than retrograde shame.

Seductive and reassuring, such “standard heroic narratives of the avant-garde” (Gesty 2) nonetheless retroactively limit our apprehension of the complex aesthetic and sexual politics that informed late-Victorian British art. As Heather Love observes, late-Victorian and early-Modernist artists who seem to turn away from a an avant-garde aesthetic of transcendence are no less challenging than their colleagues who, like Epstein, seem to anticipate such modern mandates: instead, we must see their “revolutionary imagination [as] bound not to the redeemed world but to the damaged world that it aims to repair” (Love 132). As David Gesty reminds us, the artists of the “New Sculpture” movement in Britain were, from the 1880s onward, actively and variously looking to “renovate the very notion of the ideal” through innovative illuminations of the relationship between art and its immediate historical context. Whether they utilized or exploded the “formal vocabularies . . . of figurative sculpture,” artists working in Britain between 1880 and 1910 were united in their pursuit of a “new vision of sculpture, pushing its boundaries and examining its foundations” (Gesty 4-5).

This essay first explores the history of how Epstein’s monument to Wilde came to be regarded as an embodiment of modernity—both in terms of sculptural aesthetics and queer politics—and how this collective sense of the monument’s modernity has scripted the structures of mourning and ritual surrounding it for over a century. The essay then turns to a counterfactual yet suggestive consideration of how an alternate memorial—one designed not by an emerging avant-garde sculptor, but by a member of Wilde’s queer circle—might have likewise (but differently) constituted a radical challenge to both prevailing sculptural aesthetics and attitudes towards queer memorial. By exposing the intricate personal, aesthetic, queer cultural histories that swirl around Wilde’s iconic tomb, I hope to offer a meditation on the complex politics of queer memorialization within literary history that recovers the radical potential of Silence in the face of communal trauma.

Pilgrimage of Love: Remembering Wilde before Père-Lachaise

Sentenced in 1885 to two years’ hard labor for “acts of gross indecency with young men,” Oscar Wilde served out his term without remittance. (See Andrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities.”) Once released from prison in May 1897, Wilde fled immediately for ![]() France, eventually basing himself in Paris where he haunted the cafes in search of conversation and conviviality. Wilde lived this bohemian boulevardier existence for three years and in declining health. Although reports of Wilde’s isolation and obscurity in his last years were perhaps exaggerated by both admirers and detractors alike, it is certainly true that Wilde died a pariah and deeply in debt. Wilde’s final illness—the treatment for which included surgery and hospice care—had been costly; Jean Dupoirier, proprietor of the

France, eventually basing himself in Paris where he haunted the cafes in search of conversation and conviviality. Wilde lived this bohemian boulevardier existence for three years and in declining health. Although reports of Wilde’s isolation and obscurity in his last years were perhaps exaggerated by both admirers and detractors alike, it is certainly true that Wilde died a pariah and deeply in debt. Wilde’s final illness—the treatment for which included surgery and hospice care—had been costly; Jean Dupoirier, proprietor of the ![]() Hôtel d’Alsace, Wilde’s last residence, had for months ceased to collect rent out of caring and respect. Wilde had indeed died—as he is remembered as saying—beyond his means.

Hôtel d’Alsace, Wilde’s last residence, had for months ceased to collect rent out of caring and respect. Wilde had indeed died—as he is remembered as saying—beyond his means.

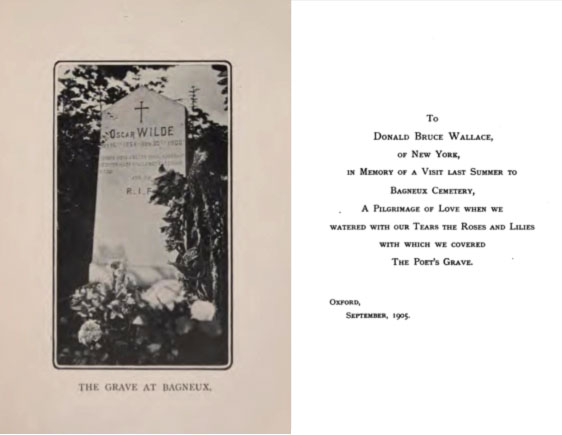

His friends did their best, but as Richard Ellmann observed, “The coffin was cheap, and the hearse was shabby” (Ellmann 584). Although even in death Wilde was certainly one of Paris’s most famous (or infamous) personages, funds were not available to purchase him a burial plot within the city limits. Furthermore, his friend and executor Robert Ross “had not yet decided what to do, or the nature of the monument” (qtd. in Hyde 376). Wilde was therefore buried in a temporary concession (a leased gravesite) southwest of Paris at the modest ![]() Cimetière de Bagneux, with the expectation that his remains would be later transferred elsewhere. In a letter written three weeks after the burial at Bagneux, Ross insisted that Wilde would, in time, be more properly remembered: “I believe I told you that the grave at Bagneux is a temporary concession. I shall either purchase the ground outright later on and erect a suitable monument, or move the remains to a permanent resting place” (“To Adela Schuster” 1228-9). This first gravesite, surrounded by an iron chain and headed with a simple stone, bore a modest, if pointed, inscription:

Cimetière de Bagneux, with the expectation that his remains would be later transferred elsewhere. In a letter written three weeks after the burial at Bagneux, Ross insisted that Wilde would, in time, be more properly remembered: “I believe I told you that the grave at Bagneux is a temporary concession. I shall either purchase the ground outright later on and erect a suitable monument, or move the remains to a permanent resting place” (“To Adela Schuster” 1228-9). This first gravesite, surrounded by an iron chain and headed with a simple stone, bore a modest, if pointed, inscription:

Oscar Wilde

Oct 16th 1854 – Nov 30th 1900

Verbis meis addere nihil audebant

et super illos stillebat eloquium meum.

Job xxix, 22.

R.I.P.

This first memorial inscription—“To my words they durst add nothing, and my speech dropped upon them”—enacts a sort of turning away from the world’s critical gaze. In its suggestion to would-be mourners visiting the grave that Wilde’s writing, perfect in itself, serves as its own best monument, this choice from the King James Bible marks Wilde’s life and life work as finished, complete, in no need of intervention or resurrection. Yet from the first, Wilde’s friends and admirers exempted themselves from the “they” of this inscription. Wilde’s remains were not moved to their permanent resting place at Père-Lachaise until the summer of 1909 (Hyde 381); it would take another five years before Jacob Epstein’s monument was unveiled and dedicated. Therefore, between 1900 and 1914, mourners and pilgrims wanting to pay tribute to Wilde transformed both the grave at Bagneux and the Hôtel d’Alsace into sites of queer pilgrimage.

Wildean pilgrimage—immortalized most recently in the 2006 ensemble cast film Paris je t’aime—started well before admirers began to adorn the monument at Père-Lachaise with flowers, graffiti, and lipstick kisses. Immediately after Wilde’s death, both the Hôtel D’Alsace and the grave at Bagneux became destinations for friends and admirers looking to pay last respects to a broken genius. In his memoir Twenty Years in Paris (1905), Wilde’s first biographer Robert Sherard recounted his participation in a 1904 group pilgrimage to both sites. The proprietor of the Hôtel d’Alsace was by that time making a profit by maintaining and renting out the apartment “exactly as it was in [Wilde’s] day,” preserving “the same articles of furniture” and even the “privez syringe” used to inject morphine “in the last months of [Wilde’s] slow agony.” “It appears from what the landlord told us,” Sherard wrote, “that hardly a week passes but that some visitor from foreign lands comes to the hotel and asks to be shown the room where Oscar Wilde died” (Sherard 455-56). Sherard’s companions on this pilgrimage were a young ![]() New York actor named Donald Bruce Wallace, who also published the first American, pirated edition of The Picture of Dorian, and the Wilde aficionado Christopher Millard, who would later publish the still-invaluable Bibliography of Oscar Wilde under the pseudonym Stuart Mason. Millard and Wallace traveled together expressly to pay homage to a queer hero; their visit to Bagneux is immortalized in Millard’s introduction to Andre Gide’s Oscar Wilde: A Study (1905), which begins with an ardent dedication and souvenir photograph memorializing this “[p]ilgrimage of Love” to Bagneux, “when we watered with our tears the roses and lilies with which we covered the poet’s grave” (Figs. 3-4).

New York actor named Donald Bruce Wallace, who also published the first American, pirated edition of The Picture of Dorian, and the Wilde aficionado Christopher Millard, who would later publish the still-invaluable Bibliography of Oscar Wilde under the pseudonym Stuart Mason. Millard and Wallace traveled together expressly to pay homage to a queer hero; their visit to Bagneux is immortalized in Millard’s introduction to Andre Gide’s Oscar Wilde: A Study (1905), which begins with an ardent dedication and souvenir photograph memorializing this “[p]ilgrimage of Love” to Bagneux, “when we watered with our tears the roses and lilies with which we covered the poet’s grave” (Figs. 3-4).

Weekly visitors to the Hôtel D’Alsace likely followed the pilgrimage template outlined by the eccentric ![]() Ohio-born Comtesse de Brémont (1864–1922), née Anna Dunphy. The Comtesse sent a heartfelt letter to Robert Ross in 1905, thanking him for a copy of Wilde’s De Profundis, and describing the day of pilgrimage the book inspired:

Ohio-born Comtesse de Brémont (1864–1922), née Anna Dunphy. The Comtesse sent a heartfelt letter to Robert Ross in 1905, thanking him for a copy of Wilde’s De Profundis, and describing the day of pilgrimage the book inspired:

I received Mr. Wilde’s book last Wednesday, and I thank you very much for sending me the copy. It is a wonderful book—the best poor Oscar ever wrote. . . . The morning after the book came, I made a pilgrimage in his memory—going first to St. Germain de Prés . . . where the requiem mass was held over his remains. I knelt in the same place & was with his soul in spirit—then I sought the

Rue des Beaux-Arts & went to the house where he died—all this gave me some consolation . . . for I was possessed by a might of sadness over his sorrows & suffering.

Bremont planned to make a full circuit of Wilde sites as a response to reading De Profundis, but found she lacked the stamina: “I shall make another pilgrimage, soon, to the grave in Bagneux, but up till now the weather has been so trying I dare not fatigue myself as I have had a slight attack of grippe” (n. pag.).

Monumental Advances

That many embarked upon such adulatory pilgrimages in 1905 and after can be explained by the publication, in February of that year, of this “wonderful book.” Wilde’s long letter to Lord Alfred Douglas was that year published posthumously in a highly expurgated edition with an introduction by Robert Ross and a cover design by Wilde’s friend and artistic collaborator Charles Ricketts. The 1905 edition of De Profundis struck many as a monologue intoned from beyond the grave—one that, in manifesting what George Bernard Shaw termed “[t]he unquenchable spirit of the man,” reiterated the tragic fact of Wilde’s early death all the more poignantly. This phonographic aura—with its suggestion of having preserved a voice speaking “from the depths,” as the volume’s title suggests—helped fuel sales: De Profundis became the vehicle through which Wilde’s estate was finally secured. The first run in January 1905 quickly sold out; by the end of the year, Methuen was in its sixth printing (Bristow, Modern Culture 14). In addition to significant proceeds from 1905/1906 productions of Richard Strauss’s adapted Salome, royalties from De Profundis made it possible for Robert Ross to secure all copyrights for Wilde’s published works. Ross then began work on an authorized “complete works” that would effectively halt the international market in pirated editions that had proliferated since Wilde’s death.

Figures 5 and 6: Programme, Dinner for Robert Ross to celebrate the publication of _The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde_ (London: Methuen, 1908), courtesy of the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA

Robert Ross’s labor of love, The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, was published in London by Methuen in 1908. In December of that year, this achievement, monumental in itself, was celebrated with an elaborate dinner for Ross at the ![]() Ritz (Figs. 5 and 6). Over one hundred of Wilde’s friends, publishers and admirers were in attendance to celebrate Ross’s success. In a speech to the gathering, Ross thanked everyone present for their role in “giving back to Oscar Wilde’s children the laurels of their distinguished father untarnished save by tears.” At the end of his speech, Ross dropped an unexpected thanks into the mix: an anonymous donor (later identified as Helen Carew) had recently sent him a cheque for £2000, “to place a suitable monument to Oscar Wilde at Père-Lachaise.” Ross continued:

Ritz (Figs. 5 and 6). Over one hundred of Wilde’s friends, publishers and admirers were in attendance to celebrate Ross’s success. In a speech to the gathering, Ross thanked everyone present for their role in “giving back to Oscar Wilde’s children the laurels of their distinguished father untarnished save by tears.” At the end of his speech, Ross dropped an unexpected thanks into the mix: an anonymous donor (later identified as Helen Carew) had recently sent him a cheque for £2000, “to place a suitable monument to Oscar Wilde at Père-Lachaise.” Ross continued:

The condition of this gift is not one to which I certainly have any objection—the condition is—that, the work should be carried out by the brilliant young sculptor, Mr. Jacob Epstein from whom Sir Charles Holyrod has already prophesied great things. (n. Pag.)

The choice of Epstein—a provocative, cutting-edge sculptor who had never known Wilde—was a bold, if impersonal one, and there was another artist in attendance on this occasion who likely took the impersonality of Ross’s choice rather hard.

Charles Ricketts, who seating charts indicate was prominently seated across from Wilde’s eldest son Cyril, had likely known for quite some time that a monument had been planned for Wilde’s tomb. As he and his lifelong companion, the painter Charles Shannon, often socialized with Robert Ross, he may even have had advance knowledge of this monetary donation, whose equivalent value today would be close to $325,000. And, as Ross knew well, Ricketts was the artist with whom Wilde had most often collaborated, and this collaboration had continued posthumously with Ricketts’s cover design for Wilde’s De Profundis. Ricketts’s journal records a January 1905 conversation between himself and Ross concerning Wilde’s tomb, and by September of that year Ricketts had labored over and produced a small bronze statuette entitled Silence. Two casts of this statuette are known to be in existence: one is housed at the ![]() William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA; the other is part of a private collection associated with the London Fine Art Society. Both are identified, although no clear provenance as of yet has corroborated this identification, as having been designed for Wilde’s tomb. In 1905 and 1906, Robert Ross had curated two exhibits of Ricketts’s bronzes at London’s avant-garde

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA; the other is part of a private collection associated with the London Fine Art Society. Both are identified, although no clear provenance as of yet has corroborated this identification, as having been designed for Wilde’s tomb. In 1905 and 1906, Robert Ross had curated two exhibits of Ricketts’s bronzes at London’s avant-garde ![]() Carfax Gallery (of which he was part owner). Both exhibits featured Silence, and in published reviews many critics noted this bronze, in particular, as one of Ricketts’s best. It is, therefore, hard to credit that Ross had not considered Ricketts as a contender for this commission; it is likewise difficult to imagine that Ricketts had not considered this himself. Therefore, on this evening in 1908, Ross’s surprise announcement of a generous commission for Wilde’s tomb likely surprised Charles Ricketts more than most.

Carfax Gallery (of which he was part owner). Both exhibits featured Silence, and in published reviews many critics noted this bronze, in particular, as one of Ricketts’s best. It is, therefore, hard to credit that Ross had not considered Ricketts as a contender for this commission; it is likewise difficult to imagine that Ricketts had not considered this himself. Therefore, on this evening in 1908, Ross’s surprise announcement of a generous commission for Wilde’s tomb likely surprised Charles Ricketts more than most.

Although their aesthetic styles could not have been more divergent, Charles Ricketts and Jacob Epstein were not adversaries; in fact, Ricketts played a key role in bringing him to the attention of Wilde’s circle. Earlier in 1908, Ricketts had been one of the many prominent London artists to defend Epstein’s first major commission: a group of eighteen eight-foot stone nudes designed to grace the façade of central London’s new ![]() British Medical Association Building. Once erected, these monuments prompted widespread outrage from conservative corners. Father Bernard Vaughan, secretary of the National Vigilance Society, opined that “[i]n no other city in Europe are figures in sculpture of the nature shown on the building in

British Medical Association Building. Once erected, these monuments prompted widespread outrage from conservative corners. Father Bernard Vaughan, secretary of the National Vigilance Society, opined that “[i]n no other city in Europe are figures in sculpture of the nature shown on the building in ![]() the Strand thrust upon the public gaze,” and predicted that “[i]f photographs of the statues were sold in public streets or exposed for sale in any shop, proceedings would at once be taken” (qtd. in Epstein 238). The Strand Statues scandal brought Epstein to the attention of many in the London art world. For Ricketts, a queer artist whose “shock and stupor” over the Wilde trials gave way to a “mistrust of the British conscience, a mistrust of modern civilization” (Self Portrait 300), the threat of yet another artist falling prey to the forces of English moral censorship demanded prompt action. Successfully defended in the papers by Ricketts, Charles Holmes, and William Rothenstein, to name just a few, Epstein’s provocative sculptures escaped demolition. Although the Strand Statues scandal may have, as many critics have noted, marked Epstein as a radical artist and thus limited his earning potential, the public debates his work engendered about the relationship between art and morality likely contributed to his being considered and ultimately chosen for a commission dedicated to the memory of an artist similarly radicalized through sexual scandal.

the Strand thrust upon the public gaze,” and predicted that “[i]f photographs of the statues were sold in public streets or exposed for sale in any shop, proceedings would at once be taken” (qtd. in Epstein 238). The Strand Statues scandal brought Epstein to the attention of many in the London art world. For Ricketts, a queer artist whose “shock and stupor” over the Wilde trials gave way to a “mistrust of the British conscience, a mistrust of modern civilization” (Self Portrait 300), the threat of yet another artist falling prey to the forces of English moral censorship demanded prompt action. Successfully defended in the papers by Ricketts, Charles Holmes, and William Rothenstein, to name just a few, Epstein’s provocative sculptures escaped demolition. Although the Strand Statues scandal may have, as many critics have noted, marked Epstein as a radical artist and thus limited his earning potential, the public debates his work engendered about the relationship between art and morality likely contributed to his being considered and ultimately chosen for a commission dedicated to the memory of an artist similarly radicalized through sexual scandal.

Jacob Epstein was as surprised as anyone to learn that he would be responsible for a permanent monument to Wilde’s memory. In his Autobiography, he records his shock upon receiving, the morning after the Ritz dinner, many congratulatory phone calls:

I heard of the commission to do the tomb of Oscar Wilde the day after it had been announced at a dinner given to Robert Ross by his friends at the Ritz. I neither knew of this dinner nor of its being made the occasion for an announcement that I was to receive the commission . . . . The rumour was confirmed later in the day, and I believe the secrecy with regard to me can only be explained by the fact that other sculptors knew of the commission and expected it to be given them, and the trustee for the monument, Robert Ross, was too timid to let it be known that I would be offered the work for fear of what these sculptors might do to hinder the plan. (Epstein 51)

Epstein’s interpretation of why Ross chose this public event to announce the commission seems plausible; as Michael Pennington observes in his history of Epstein’s monument, William Rothenstein (also present at the 1908 Ritz dinner) had, by 1908, become Epstein’s most dedicated champion—and it was likely Rothenstein, not Helen Carew, who persuaded Ross to choose this controversial artist for the commission (Pennington 14). It is certainly curious that Ross, “a cautious man” who, as Wilde’s first male lover, had experienced his own share of scandal, in the end chose to offer this commission to an artist whose primary notoriety “was, in essence, a sexual one” (14). But in some ways, Epstein was the cautious choice. As an artist trying to make it in turn-of-the-century London, Epstein shared with Wilde a certain outsider status: Wilde was an Irish sexual libertine, Epstein was a lower East Side Jewish New Yorker and sexual libertine. Yet Epstein had neither known Wilde, nor was he part of an extended circle of queer artists who might risk exposure by association if chosen for the commission. Ross may have chosen an artist unconnected with Wilde to shield his own queer community from collateral damage. Additionally, as a gallery owner who counted many artists among his close friends, Ross likely welcomed the plausible deniability against accusations of favoritism this less intimate allocation afforded him. It seems, then, that Epstein was correct in surmising that Ross likely chose this broad public occasion for his announcement because others did know about the commission and expected it to be assigned elsewhere. In particular, Ross made this announcement in the presence of Charles Ricketts, who had already created a memorial sculpture to Wilde quite unlike anything Epstein would create in both symbolic power and material execution.

Epstein’s “Winged Demon-Angel”

Figures 7 and 8: Jacob Epstein in his London studio with the Tomb of Oscar Wilde, c. 1912 and detail of the Tomb of Oscar Wilde, c. 1912 (photographs by E.O. Hoppe, courtesy of the University of Reading)

Unlike Silence, Ricketts’s comparatively quieter memorial to Wilde, Jacob Epstein’s striking bas-relief tomb was executed through the direct carving techniques that would be so closely associated with twentieth-century avant-garde sculpture, and thus sutures Wilde’s memory to the future. Epstein’s Tomb of Oscar Wilde was heavily influenced by the ancient Indian, Egyptian and Assyrian winged sphinxes the sculptor studied at length at the ![]() British Museum. As Stephen Gardiner observes, the works Epstein studied possessed an “immense vitality,” and a “highly complex construction,” but perhaps the most important element Epstein borrowed from these sculptures was the impression of a “sculpture in evolution—three-dimensional forms emerging from the graphic diagram of the relief: in almost every instance, there is a flat back, a front sculpture, and . . . a stone frame for the whole” (Gardiner 84). Retaining the great heft and bas-relief aspects of these ancient sculptures as a starting point, Epstein added an almost brutal simplicity of line and a sensual, otherworldly androgyny to his execution of the front sculpture, marking his “Tomb for Oscar Wilde” as a radical and modern departure from the figural realism of nineteenth-century European sculpture. Epstein drew inspiration from Wilde’s writing and personal history as well as from Charles Ricketts’s decadent and intricate illustrations for Wilde’s poem “The Sphinx” to imagine Wilde’s tomb. The tension between ancient and modern sources, mediated through a grammar of ornament inspired largely by the Ricketts/Wilde collaboration, is used to great effect in the finished sculpture. Hewn from a twenty-ton block of

British Museum. As Stephen Gardiner observes, the works Epstein studied possessed an “immense vitality,” and a “highly complex construction,” but perhaps the most important element Epstein borrowed from these sculptures was the impression of a “sculpture in evolution—three-dimensional forms emerging from the graphic diagram of the relief: in almost every instance, there is a flat back, a front sculpture, and . . . a stone frame for the whole” (Gardiner 84). Retaining the great heft and bas-relief aspects of these ancient sculptures as a starting point, Epstein added an almost brutal simplicity of line and a sensual, otherworldly androgyny to his execution of the front sculpture, marking his “Tomb for Oscar Wilde” as a radical and modern departure from the figural realism of nineteenth-century European sculpture. Epstein drew inspiration from Wilde’s writing and personal history as well as from Charles Ricketts’s decadent and intricate illustrations for Wilde’s poem “The Sphinx” to imagine Wilde’s tomb. The tension between ancient and modern sources, mediated through a grammar of ornament inspired largely by the Ricketts/Wilde collaboration, is used to great effect in the finished sculpture. Hewn from a twenty-ton block of ![]() Derbyshire Hopton-Wood limestone, Epstein’s monument to Wilde seems comprised equally of lightness and heft. The winged angel that adorns the monument’s face floats almost free from a squared-off backing. Its wings, which take up almost the whole of the monument’s upper half, seem only partially up to the task of carrying the body beneath. This body, although sexed masculine, appears painfully fragile and about to break. Its face, carved into the side of the monument, is likewise delicate, the eyes swollen shut, as if the figure had been abused. Although this side-facing design gives the impression of a figurehead breaking the waves into the future, the solid block behind the figure and the base on which it rests anchor the tomb in earth-bound permanence.

Derbyshire Hopton-Wood limestone, Epstein’s monument to Wilde seems comprised equally of lightness and heft. The winged angel that adorns the monument’s face floats almost free from a squared-off backing. Its wings, which take up almost the whole of the monument’s upper half, seem only partially up to the task of carrying the body beneath. This body, although sexed masculine, appears painfully fragile and about to break. Its face, carved into the side of the monument, is likewise delicate, the eyes swollen shut, as if the figure had been abused. Although this side-facing design gives the impression of a figurehead breaking the waves into the future, the solid block behind the figure and the base on which it rests anchor the tomb in earth-bound permanence.

In June 1912, Epstein’s provocative mix of ancient and modern was exhibited in his London studio to great general acclaim (Figs. 7 and 8). Given that the choice of Epstein to carve Wilde’s tomb represented a potentially explosive merger of two artists infamous for pushing the limits of artistic decency, the relative moral merits of Epstein’s monument to Wilde—the naked figure adorning which struck many as uncannily resembling the deceased—prompted surprisingly little negative comment from the press. The New York Times London correspondent visited Epstein’s studio to view the monument, and recorded: “It is a strange, weird, haunting conception, this massive, squarely-blocked-out tomb to which is attached a very archaic winged figure, with the somewhat conventionalized features of Oscar Wilde” (“Art Notes” 15). One month later, the paper reported again on Epstein’s memorial, quoting another viewer’s take on the figure:

A demon-angel, nine feet in lengt. . . is shown in flight. A go-between of earth and heaven, but with wings for flight stronger than the lithe earth limbs, the face wide, oval and full, with more of the earth than heaven in it, part-Isis, part-Celt, inexplicable, sensuous without being sensual, and as wholly secretive of its own thoughts as the ternal Sphinx—this is the spirit chosen to keep Wilde’s memory green. Some of Wilde’s friends declare that the face is reminiscent of him. But Mr. Epstein stoutly denies any intention of a resemblance. (“Memorial to Oscar Wilde” 1912, C4)

Considering that multiple viewers (including Wilde’s friends) noted a physical resemblance between this fragile, sensuous, androgynous, Celtic “demon-angel” and Wilde himself, the Pall Mall Gazette’s positive response to Epstein’s memorial, although open-minded regarding Wilde’s legacy, seems intent on dislodging the viewer’s understanding of the figure from any literal feelings she might have about the historical Wilde’s ill-treatment or untimely death:

It is obvious that Mr. Epstein did not propose to be either a literary or moral critic of Oscar Wilde. This brooding, winged figure, born long ago in primitive passions, is a child of marble, and . . . has been created in anguish under the driving possession of an idea. The hand of the sculptor has groped in the block of marble impelled to the expression, without words or definition, of the haunting tragedy of a great career. How you are to apply this figure to the facts of Oscar Wilde’s life—to his work or his character—is not a question that arises. (qtd. in Epstein 251)

Yet from the moment it was transported to Paris’s Père-Lachaise cemetery, where Wilde’s body waited after being exhumed, moved, and reinterred in 1909, Epstein’s sexed sphinx was read by both admirers and detractors alike as a limestone embodiment of the embattled Celt, and this conflation of the monumental and the corporeal fueled the international scandal that marked the Tomb’s installation.

Once installed over Wilde’s grave, Epstein’s monument became inseparably entangled with biographical “facts.” Arriving from London to complete the details of the elaborate headdress adorning his “flying demon-angel” (Epstein 51), Epstein found his creation covered and guarded—“[a]rrested,” in the formulation of Ross, under whose direction the tomb had been commissioned and who would be interred there in 1950 along with his former lover and friend. Writing to the Pall Mall Gazette in September 1912, Ross caustically noted the irony of Wilde’s tomb being censored for indecency not in England, but Paris:

I regard the arrest of the monument by the French authorities simply as a graceful outcome of the Entente Cordial and a symptom on the part of our allies to prove themselves worthy of political union with our great nation, which rightly or wrongly they think has always put Propriety before everything. I hesitate to say that the rest lies in the lap of the gods, for that is exactly the part of the statue to which exception is taken. (qtd. in Pennington 52)

Paris authorities attempted to solve the problem clumsily and with little respect for the artist: “Imagine my horror,” Epstein wrote to a friend, “when arriving to the cemetery to find that the sex parts of the figure had been swaddled in plaster! and horribly.” Consultation between the Prefect of the ![]() Seine and the Keeper of the

Seine and the Keeper of the ![]() École des Beaux-Arts resulted in a decree: “I must castrate or fig leaf the monument! What am I to do?” (qtd. in Pennington 49). Brought to Paris in August 1912, the monument remained in situ for almost two years, obscured from public view by “an enormous tarpaulin, and a gendarme standing besides it” (Epstein 52).

École des Beaux-Arts resulted in a decree: “I must castrate or fig leaf the monument! What am I to do?” (qtd. in Pennington 49). Brought to Paris in August 1912, the monument remained in situ for almost two years, obscured from public view by “an enormous tarpaulin, and a gendarme standing besides it” (Epstein 52).

To Epstein, this all felt like a repeat of the 1908 Strand Statues scandal. This was only his second major commission, and public morality was again interfering: “Here is the Strand business all over again,” Epstein wrote. “You cannot imagine how terrible the monument looks now. . . . I feel quite sick over it but ridicule will do the work I think. Imagine a bronze fig leaf on the Oscar Wilde Tomb. For that is what the guardian of the cemetery suggested might be done” (49). Protests from English, French, Irish and American artists and critics were to no avail; ultimately, the fig-leaf solution was chosen. Eager to settle this issue and remove Wilde’s name from the voracious press coverage of (yet another) sex scandal, Robert Ross pressed Epstein to allow a bronze cache-sexe in the shape of a butterfly to be affixed to the monument. Outraged, Epstein refused to attend the unveiling. The August 1914 ceremony was attended by a strange confluence of outcasts and was presided over by the occult leader Aleister Crowley. Legend has it that weeks later Crowley returned to the grave, removed the butterfly from the monument, and wore it around Paris as a cod-piece (Pennington 55).

The tomb remained unadorned by any fig leaf or cod piece until 1961, when vandals chiseled off the genitals altogether. Giles Robertson, then joint executor of the estate of Robert Ross, offered historian Michael Pennington one rationale for this late act of censorship. Robertson observed that by the early 1950s, the tomb had become increasingly notorious as “a place of pilgrimage to the homosexual community” and that, as a result, Epstein’s sculpture was now covered with a layer of accumulated graffiti expressing that community’s reverence for Wilde. “He noted, in particular,” writes Pennington, “the extraordinarily polished, shiny quality of the angel’s pendulous testicles by comparison with the dull, grainy texture of the rest of the tomb. He realized that their unusual appearance was due to the continual touching, stroking and caressing by the hands of the homosexual admirers in worship and reverence to those parts of Oscar Wilde for which they believe he was martyred” (60-61). Whether or not this rationale holds water (we might question, for instance, whether only “homosexual admirers” paid homage at Wilde’s tomb, or whether all of this “reverence” was in earnest), it leads directly to the urban legend accounting for who chiseled off “those parts.” Pennington records the story, told by Michel Dansel in his book Au Père Lachaise, of two English ladies who enjoyed walking together in the cemetery but who were scandalized by the prominent display of male genitalia the burnished monument imposed upon them. The outraged ladies (who, it seems, were only selectively “proper” in their adherence to conventional morality) grabbed several rocks that lined the alley near the tomb and hacked away at the sculpture’s genitals, finally removing them entirely. The severed stone member was then collected by the Père-Lachaise conservation department, where it is said to have served as a paperweight for many years (Pennington 61). This item is now missing, and the monument remains sexless.

Epstein’s winged demon-angel has always, for better or worse, stood in as proxy for Wilde’s physical body. Inspired by the sensuality of Wilde’s writing and life, Epstein crafted a figure of erotic dignity that has inspired admirers to physical response. And such open, public affection for one imagined as a queer martyr—whose bruised, swollen, yet forward-looking stone countenance looks defiantly towards the future—has served as public protest against rigid sexual morality for over a century. Although methods of adulation have shifted over time, they always retain a sense of rebellious openness, one that responds to both the power and the fragility that marks Epstein’s sculptural style. The “Wilde” being adored in Père Lachaise is a Wilde defiantly bold yet invested with fragility, imperious in his ability to resist any attempts to defile or contain him, yet powerfully seductive in his ability to solicit physical acts of both affection and outrage. In 1912, it was under wraps and guarded; up until 1914, it was the site of numerous public protests decrying the prudery behind the monument’s suppression. Once freed of both butterfly codpiece and tarp, the monument was visited regularly and adored, even after its castration in the early 1960s. Kissing the tomb became popular later in the century, and this rise in performative and public adulation might be productively mapped onto changing attitudes to both Wilde and the LGBTQ community in the aftermath of the AIDS crisis—for if, as the direct-action AIDS advocacy group ACT-UP demanded, “Silence = Death,” what better way to break that silence than to openly adore one who died for the “love that dare not speak its name?”

Yet by November 2000, the 100th anniversary of Wilde’s death, this practice of kissing Epstein’s monument had so steadily damaged the English limestone out of which it is carved that many began calling for action (figs. 9-10). In November 2011, one hundred years after the monument’s installation, the Irish government partnered with Wilde’s grandson, Merlin Holland, to have the monument carefully cleaned and sealed from future displays of adoration. A glass barrier now encircles the monument, intended as insurance against further deterioration. Despite this prophylactic solution—which ensures that any graffiti can be wiped away with Windex—bold admirers still find ways to adorn the monument with kisses. And those who are less agile (or more law abiding) now throw written messages, flowers, and other items of remembrance over the glass barrier (figs 11-12).

Figures 11 and 12: Epstein’s Tomb of Oscar Wilde after cleaning and installation of glass panels, March 2012 (photographs by the author)

A lingering memory of the suppression of Epstein’s monument—and the way that suppression recreated the public shaming and silencing of Wilde through his trial and early death—influenced the particular rituals of mourning and admiration that grew up around the tomb at Père-Lachaise. Wilde’s first grave at Bagneux had certainly been a place of pilgrimage for admirers at the start of the twentieth century, as had the Hôtel D’Alsace. But it is with Epstein’s monument and its history of passionate admiration from pilgrims assumed to be either queer or queer-friendly that we associate Wilde’s memory; his status as queer martyr is inexorably bound up with the history of his tomb and its visitors. But how might this history have been different had Ross chosen not Epstein, but instead Charles Ricketts, as the sculptor to receive the Père-Lachaise commission? It is to this experiment in counter-factual cultural history that the remainder of this essay will be devoted.

Ricketts, Silence, and Père-Lachaise

Figure 13: Charles Ricketts, Silence (detail), 1905 (courtesy of the William

Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA; photograph by the author)

Charles Ricketts, who had collaborated with Wilde on the designs for all but one of his books published before his imprisonment, took the news of his friend’s death very hard. In a journal entry on 5 December 1900, he records the circumstances under which he heard the news and his initial response:

[T. Sturge] Moore brought to-day the news, some days old, of Oscar’s death. I feel too upset to write about it, and the end of that Comedy that was really Tragedy. There are days when one vomits one’s nationality, when one regrets that one is an Englishman. I know I have not really felt the fact of his death, I am merely wretched, tearful, stupid, vaguely conscious that something has happened that stirs up old resentment and that one is not sufficiently reconciled to life and death. Moore had hardly finished giving us the news when a loud ringing was heard and Michael Field arrived, sobbing loudly in the hall. (Ricketts 49)

Two weeks later, he records a fitful night of grieving: “Dreamt all last night about Oscar Wilde, or what seems so to me, for I woke up and fell asleep again more than once.” And on the eve of 1901, he notes that in a year otherwise marked with professional accomplishments there remained “One sorrow: the death, at first hardly felt, of poor Oscar Wilde; this affects one at stray moments, when one is off one’s guard: at sundown, or at sunrise: moments, with me, of introspection, hesitation, or regret” (Ricketts 50). When Ricketts and Shannon travelled to Paris three months later to attend an exhibition at the Palais de l’École des Beaux-Arts, the couple could not have avoided thoughts of their old friend: the entrance to the exhibition, at the intersection of the ![]() Rue Bonaparte and the Rue des Beaux-Arts, was a mere four doors up from the Hôtel D’Alsace, Wilde’s final residence. Ricketts and Shannon would have been aware of Wilde as they entered the exhibition, and given Ricketts’s grief-stricken response to Wilde’s death, it is not difficult to imagine the couple making their own pilgrimage to the Hotel, if not to Wilde’s temporary grave at Bagneux. Both sites would have likely struck this aesthetically minded pair as singularly and unsuitably inartistic.

Rue Bonaparte and the Rue des Beaux-Arts, was a mere four doors up from the Hôtel D’Alsace, Wilde’s final residence. Ricketts and Shannon would have been aware of Wilde as they entered the exhibition, and given Ricketts’s grief-stricken response to Wilde’s death, it is not difficult to imagine the couple making their own pilgrimage to the Hotel, if not to Wilde’s temporary grave at Bagneux. Both sites would have likely struck this aesthetically minded pair as singularly and unsuitably inartistic.

When, four years later, Ricketts received from Robert Ross an advance copy of De Profundis, he was struck anew by the tragedy of Wilde’s downfall and death: “Read Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis. . . . It is tragic reading, tragic in statement and tragic between the lines, more tragic than the author seems to know” (Self Portrait 112-13). Ross asked Ricketts to design the cover; Ricketts chose a simple gilt image, stamped on blue cloth boards, of a bird escaping from behind prison bars (Figs. 11-12). On the eve of the volume’s publication, Ricketts paid a visit to Ross, and the two spent the evening reminiscing about Wilde:

In the evening to see Ross, who is ill. He told me a charming story about Oscar. “Ah Ross! When we are dead in our Porphyry tombs, when the trump of the last judgment is sounded, I shall turn and whisper to you, ‘Robbie, Robbie, let us pretend we do not hear it’” (Ricketts 114).

From the work he produced over the course of 1905, it seems clear that Ricketts was listening to Ross’s “charming story” about Wilde in his tomb with a working artist’s ear. This image—two lovers huddled silently, evading final judgment in preference for an eternity entombed together—stayed with Ricketts. By the summer of 1904, Ricketts had, in his words, “turned sculptor,” crafting several small figures in clay (Delaney 190). After a year spent intensely focused on Wilde’s De Profundis, in September 1905 he produced a small bronze statue that, in the few times it has been catalogued or exhibited over the last hundred years, has been identified as a rejected design for the tomb of Oscar Wilde. Unlike Epstein’s bold sculptural challenge to future generations, this alternative memorial echoes the evasively secretive spirit of Wilde’s queer challenge to the concept of “last judgment.” Entitled “Silence,” Ricketts’s statue advocates radical reserve as posthumous protection against normative judgment (Figs. 16-18).

Figures 16-18: Charles Ricketts, Silence (full figure and details), 1905 (courtesy of the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA; photographs by the author)

Although Ricketts nowhere directly identifies Silence as a memorial to Wilde, his journals suggest that Wilde dominated his thoughts during its composition. On 7 September 1905, he records working all day on the “[f]igure of ‘Silence’ (a statuette)” following a night plagued by nightmares about death. 8 September was spent working “nine hours on figure of ‘Silence,’” and over the next few weeks he kept at it slowly. On 23 September, he returned home to his journal after attending the first revival of Wilde’s An Ideal Husband at the ![]() Coronet Theatre: “Continued tinkering. Of this there is no end,” he began, and then spent the rest of his entry thinking about Wilde:

Coronet Theatre: “Continued tinkering. Of this there is no end,” he began, and then spent the rest of his entry thinking about Wilde:

Oscar was always better than he thought he was, and no one in his lifetime was able to see it, including my clairvoyant self. It is astonishing that I viewed him as the most genial, kindly, and civilized of men, but it never entered my head that his personality was the most remarkable one that I should ever meet, that in intellect and humanity he is the largest type I have come across. Other men of my time were great in some one thing, not large in their very texture. (124-5)

Through this period of intense concentration, Ricketts worked so hard on Silence that he often felt “dizzy from overwork” (124); this intensity produced a sculpture infused with the “texture” of Wilde and the history of the two artists’ personal and working relationship.

Ricketts and Shannon shared with Wilde (and other artists of the late-Victorian period) an appreciation for the fluid modernity and sensual grace of Tanagra statuettes. These small Greek terracotta figurines from the fourth century, often covered in slip and vibrantly painted, depicted everyday women in draped, fluid clothing. These artists clearly delighted in their ability to reveal the contours of the human body through suggestive depictions of drapery’s movement. Silence, in both its diminutive size and its sensitivity to sensuous physical movement beneath flowing drapery, pays homage to this common aesthetic interest. The majority of Ricketts’s sculptures from this period are nudes; Silence is one of his only clothed bronzes. It was this Tanagra-like emphasis on drapery that was singled out for admiration by the Athenaeum in its review of a January 1906 exhibition at the ![]() New Gallery of work by the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers:

New Gallery of work by the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers:

Mr. Charles Ricketts, who is perhaps the most varied and accomplished technician in England, has also of late turned his attention to sculpture, and his bronzes have appeared from time to time in small exhibitions. Nothing that we have seen so far comes up to the level of the small figure of Silence. The form has great beauty and unity of silhouette, and the drapery is disposed with Mr. Ricketts intense and instinctive feeling for rhythm. (“The New Gallery” 56: italics original)

Ricketts’s design for Silence also draws upon several earlier drawings developed for Wilde’s books before the author’s tragic fall. As Stephen Calloway notes in Charles Ricketts: Subtle and Fantastic Decorator, in Ricketts’s sculptures one often finds references to earlier designs, “such as in the beautiful single standing figure, Silence, which is based on one of the page ornaments in A House of Pomegranates [1891], drawn fifteen years earlier” (Calloway 22).

Figure 19 (left): Page decoration from Wilde, _A House of Pomegranates_ (Osgood & McIlvaine, London 1891). Figure 20: Detail from title page, Wilde, _A House of Pomegranates_ (Osgood & McIlvaine, London 1891)

In both its singular hand gesture and its winged headdress, Silence clearly remembers this page decoration from A House of Pomegranates (Fig. 19). The statue’s drapery and her barefooted stance also recall the imagery Ricketts designed for the volume’s title page (Fig. 20). Ricketts continued, however, to create variations on this figure for his Wilde illustrations. In the figure that adorns both the cover and internal illustrations for the 1894 limited edition deluxe version of Wilde’s The Sphinx, we find a draped figure in winged headdress gesturing—although the meaning of the gesture is here more ambiguous (Fig. 21). This symbolic figure, loosely identified in the volume’s frontispiece as “Melancholia,” follows the androgynous Sphinx as she searches for her dead lovers (Fig. 22). Importantly, The Sphinx is a text that is echoed in both extant sculptural memorials to Wilde: Ricketts’s and Epstein’s. Whereas after surveying all of Wilde’s written work, including this Ricketts-illustrated volume, Jacob Epstein chose the enigmatic, androgynous Sphinx as the heraldic figure to preside over Wilde’s tomb, Ricketts himself resurrected “Melancholia”—the one who follows, the one left behind—as a mournful figure to preside over Wilde’s memory. Whereas Epstein’s choice stresses a heroic solitude—the future-oriented figure in half-flight from a hostile present—Ricketts’s choice highlights relationality, community, and loss.

Figures 21 and 22: Charles Ricketts, cover design and detail illustration from _The Sphinx_, by Oscar Wilde (London: Elkin Matthews and John Lane, 1894)

What connects all of these interlocking Wildean aspects that together forged Ricketts’s memorial to a dead friend is their common preference for suggestiveness, subtlety, quietude and introspection. Ricketts’s Silence is a sculpture that, above all, invokes privacy. Having shared with Wilde a fear of public exposure, Ricketts and his lover Charles Shannon had lived and worked together since their early twenties, and both their liberty and livelihood depended upon living a discreet existence. That Wilde had been less than discreet was certainly Ricketts’s sense; Wilde’s trials and imprisonment brought “widespread sorrow and suffering” to his entire community: “To me, the shock and stupor were slow to pass away . . . something happened from which I have never quite recovered, a mistrust of the British conscience, a mistrust of modern civilization” (Ricketts 299-300). Silence is therefore a sculpture that seems to imply the viewer’s participation in a shared secret history—which, given the anecdote about Wilde in his tomb, can be read as silence shared between lovers afraid that a final judgment will separate them forever. Whereas one might read the figure’s appeal for silence as retrogressive turn back into the closet and therefore the past, the figure’s mournful yet proud gesture might be more suggestively read as casting a protective, communal pall over Wilde’s grave to ensure against future judgment or exposure.

The statue was first exhibited at the New Gallery in January 1906; it was subsequently shown with seven other bronzes at the Carfax Gallery in March of that year in a joint exhibition of Ricketts’s sculptures and drawings by Ludwig von Hofmann, curated by Robert Ross. The Carfax catalogue for this exhibition lists the price for each bronze and a number of plaster casts to be made from each sculpture; Silence was listed at £25, with up to 25 plaster casts permissible (British Sculpture 16). At least two bronze casts of Silence are in existence; one is in private hands. The other is held at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA. The privately owned cast was recently displayed as part of the ![]() Victoria and Albert Museum’s “Cult of Beauty” exhibition (2 April – 17 July 2011); the V&A exhibition catalog identifies Silence as a “figure for the tomb of Oscar Wilde” (Calloway 230). The Clark Library bronze was purchased in 1954 from the London rare books dealers G.F. Sims; the original card catalog entry for the item unambiguously identifies Silence as having been “submitted” (and rejected) as a design for Wilde’s tomb (Fig. 23).

Victoria and Albert Museum’s “Cult of Beauty” exhibition (2 April – 17 July 2011); the V&A exhibition catalog identifies Silence as a “figure for the tomb of Oscar Wilde” (Calloway 230). The Clark Library bronze was purchased in 1954 from the London rare books dealers G.F. Sims; the original card catalog entry for the item unambiguously identifies Silence as having been “submitted” (and rejected) as a design for Wilde’s tomb (Fig. 23).

Figure 23: Catalogue Card for Ricketts’s Silence (courtesy of the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA; photograph by the author)

An undated letter from Ricketts to the great Edwardian actor Sir John Martin Harvey, also at the Clark, is annotated by another hand identifying Harvey as having once owned Silence: “Ricketts designed and made a bronze figure named ‘Silence,’ which he designed and made for his old friend Oscar Wilde, and which was bought by Sir John Martin Harvey, now in the possession of his daughter” (n. Pag.). The two bronze casts known today to exist are both identified as having been designed, and rejected, for Wilde’s tomb at Père-Lachaise.

Additionally, one plaster cast of Silence exists, and I suggest that it too should be identified as a memorial to Wilde (Figs. 24-26). Although no record of its purchase or acquisition exists, an uncatalogued, damaged, but provocatively painted plaster cast of Silence is housed at the Clark. Done in rich blues, pinks and golds, this plaster cast recalls all the more strongly Ricketts’s interest (shared with Wilde) in Tanagra statuettes. However, the statue’s color scheme also provocatively links Silence to another shared queer history. Although we know from a 1906 Carfax Gallery exhibition catalogue that Ricketts authorized the manufacture of up to 25 plaster casts of Silence, Ricketts biographer J. G. P. Delaney is the only scholar to mention the existence of any such cast. Delaney records that in 1910 Ricketts learned that his friend Edith Cooper was dying of cancer. Ricketts and Shannon had long counted Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper—the literary aunt/niece lesbian partnership known under the collective penname “Michael Field”—among their closest friends. And, as I mention above, Bradley and Cooper, along with T. Sturge Moore, were the first to mourn with Ricketts the death of their mutual friend Oscar Wilde. In Ricketts’s memory, Bradley and Cooper would have been closely associated with the extended queer circle that were affected by and mourned Wilde’s downfall and untimely death.

Figure 24: Miniature of Edith Cooper, 1901 (courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge); Figure 25: Plaster cast of Silence (courtesy of the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA; photograph by author); Figure 26: Detail, Silence plaster cast (photograph by author)

During her final illness, Edith Cooper looked forward to Ricketts’s regular visits, to which he always brought gifts. This was a generosity that surprised Cooper, who observed in her journal: “I never thought the freakish aesthete of the Vale could be so brotherly in sweetness and charity to those stricken by sorrow and disease” (qtd. in Delaney 274). One of these gifts was, as Delaney records, “a plaster cast of ‘Silence,’ his memorial to Wilde, which, as Sturge Moore later told them, was modeled on Miss Cooper” (272). Because Ricketts and Cooper mourned Wilde’s death together, he seems to have associated her with his grief and therefore incorporated her image into his memorial sculpture. This plaster cast of “Silence,” which Ricketts may have painted after hearing that Cooper was ill, is carefully composed in colors that remember the warm pink, blue and gold palette Ricketts chose for a 1901 miniature portrait of Cooper herself (Fig. 21)—whose fair skin and pale reddish hair Ricketts had admired as “exactly like” the women of Renaissance paintings (Delaney 140). This palette also recalls that of the Pre-Raphaelite painters Ricketts and Cooper mutually appreciated. Taken together, these details compellingly suggest a rich history for this plaster cast-with-no-provenance, long hidden away in the Clark Library archives (Figs. 24-26). This version of Silence was likely one decorated by Ricketts to honor a cherished, dying member of a fast-dwindling late-Victorian queer circle—one that once included Wilde. The statuette’s evocative gesture commemorates multiple events within this circle: the Wilde Trials and the threat of exposure they represented to his queer friends; Wilde’s death and the end of suffering many who cared deeply for him felt death offered; and this most recent tragedy—Cooper’s diagnosis of inoperable cancer, that would end another partnership, the true nature of which needed to be covered in silence until the end.

Silence, then, is a sculpture complexly entwined not only with Wilde’s memory, but with what Wilde’s tragedy represented to those in his extended queer circle. Ricketts’s own carefully recorded preoccupation with Wilde during the creation of the sculpture, as well as clear iconographic details linking Silence to earlier aesthetic collaborations between Ricketts and Wilde, suggest that Silence was indeed created as a memorial to Wilde, as numerous sources have suggested but never verified. But perhaps verifying Ricketts’s intentions behind this sculpture is less important than one might think, given that the statue is today widely identified as having been so intended. Ricketts’s Silence, whether or not it was intended to one day adorn the tomb at Père-Lachaise, offers us a glimpse into a pivotal moment in queer history, and into how the medium of sculpture in the Edwardian period marshaled the symbolic to express layered, if opaque, erotic histories. If such a reticent aesthetic seems at odds with the more confrontational avant-garde expressionism of a sculptor like Epstein, whose work, despite being contemporaneous with that of Ricketts, is more readily categorized under the heading “modernist,” this may be a problem of vantage point. In a cultural moment that measures the success of queer activism by increasing benchmarks of openness, we perhaps find it difficult to see the radical aesthetic potential in silence, secrecy, and refusal during an era scarred by queer scandal.

Had Silence adorned the tomb at Père-Lachaise, Wilde’s gravesite would not stand out from most other monuments in the cemetery, as it does so resolutely now. Wilde’s tomb might therefore not have become the site of creatively physical demonstrations of love and respect; it is difficult to imagine throngs of admirers kissing Silence, even more difficult to conceive of any puritanical shows of outrage over the sculpture’s mode of memorializing a dead friend. Ricketts’s design would seem to fit comfortably into the dominant aesthetic of the cemetery, looking serenely backwards towards the nineteenth century rather than defiantly forwards towards the twenty-first. Yet such an orientation does not, as narratives of queer progress so often maintain, necessarily indicate shame, repression or closeted self-preservation. Although Ricketts’s sculpture seems to advocate sealing Wilde’s memory in “Silence,” that silence speaks volumes about the constitutive histories of shame and loss that shaped an entire generation, of which Wilde and Ricketts were a part.

published November 2012

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Crowell, Ellen. “Oscar Wilde’s Tomb: Silence and the Aesthetics of Queer Memorial.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

“Art Notes from London.” The New York Times 30 June 1912: SM15. Proquest Historical Newspapers. Web. 22 June 2012.

Bremont, Anna. Letter to Robert Baldwin Ross. 8 March 1905. MS. Box 6, Folder 31. Oscar Wilde and his Literary Circle Collection. UCLA William Andrews Clark Memorial Lib., Los Angeles.

Bristow, Joseph. “Introduction.” Oscar Wilde and Modern Culture. Ed. Joseph Bristow. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2008. 1-45. Print.

British Sculpture 1850-1914: Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Sculpture and Medals Sponsored by the Victorian Society, 30th September—30th October 1968. London: Fine Art Society Ltd., 1968. Print.

Calloway, Stephen. Charles Ricketts: Subtle and Fantastic Decorator. London: Thames and Hudson, 1979. Print.

Calloway, Stephen and Lynne Orr, eds. The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900. London; V&A Publishing, 2011. Print.

Delaney, J. G. P.. Charles Ricketts: A Biography. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990. Print.

Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. New York: Knopf, 1987.Print.

Epstein, Jacob. An Autobiography. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1955. Print.

Gardiner, Stephen. Epstein: Artist Against the Establishment. New York: Viking, 1993. Print.

Gesty, David, ed. Sculpture and the Pursuit of a Modern Ideal in Britain, c. 1880-1930. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. Print.

Gide, Andre. Oscar Wilde: A Study. Ed. Stuart Mason. London: Holywell, 1905. Print.

Holland, Merlin, ed. The Collected Letters of Oscar Wilde. New York: Holt, 2000. Print.

Hyde, H. Montgomery. Oscar Wilde. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975. Print.

Love, Heather. Feeling Backwards: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2007. Print.

Mason, Stuart [Millard, Christopher]. Bibliography of Oscar Wilde. London: T. Werner Laurie, 1914. Print.

“Memorial to Oscar Wilde: Sculptor’s Work a Demon-Angel with the Face of a Sphinx.” The New York Times 25 Feb. 1912: C4. Proquest Historical Newspapers. Web. 20 June 2012.

“The New Gallery.” Athenaeum. 13 Jan. 1906: 56. Google Book Search. Web. 18 June 2012.

Pennington, Michael. An Angel for a Martyr: Jacob Epstein’s Tomb for Oscar Wilde. Reading: Whiteknights Press, 1987. Print.

Ross, Robert. “Remarks on the Occasion of the 1908 Methuen Complete Works of Wilde.” TS. Unbound, boxed collection. UCLA William Andrews Clark Memorial Lib. Los Angeles.

—. “To Adela Schuster.” 23 December 1900. Holland 1227.

Ricketts, Charles. Self Portrait: Letters and Journals of Charles Ricketts. Ed. Cecil Lewis. London: Peter Davies, 1939. Print.

—. Letter to Sir John Martin-Harvey. 1912. MS. Box 54, Folder 1-3. UCLA William Andrews Clark Memorial Lib., Los Angeles.

Sherard, Robert. Twenty Years in Paris. Philadelphia: G. W. Jacobs, 1905. Print.

Wilde, Oscar. De Profundis. London: Methuen, 1905. Print.

—. The Picture of Dorian Gray. New York: Charterhouse, 1904. Print.

—. The Sphinx. London: Elkin Matthews and John Lane, 1894. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Andrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities”