Abstract

The 1857 financial crisis began in the United States and reached England in October of that year with the fall of the Liverpool Boro’ Bank. This essay examines representations of and responses to the crisis by some of the major figures and key sources of the period. While an increasingly widespread acknowledgement of the inevitability, at times even of the desirability, of crisis manifests itself in various representations and discussions of the financial crisis, the diverse ideological assumptions and expectations of various writers, politicians, and journalists proffer widely differing explanations and solutions. These range from Marx and Engels who saw in the crisis the opportunity for revolution, to entrenched capitalists who regarded it as a necessary occurrence for the promotion of further growth, to politicians and bankers who called for new interventions in the Banking system. Through an investigation of political, journalistic, and academic responses to the 1857 crisis and the suspension of the Bank Charter Act of 1844, this paper explores the political and economic significance of the crisis for mid-century global capitalism and the Banking system.

While the actual financial crisis itself (in contrast to the industrial crisis that followed) was short-lived, the 1857 crisis remains significant for three reasons, all pertinent to twenty-first century capitalism: its implications were global in that it is commonly regarded as the first world-wide financial crisis; as the first crisis that demanded not only the suspension of Peel’s Act but also its violation, it brought to the fore the growing relationship between the State and capitalism and raised fundamental issues regarding state intervention in the banking system; and, finally, it laid bare that the cycles of boom and bust consistently inscribed as aberrations are intrinsic to the functioning of capitalism.[1] Financial crises had occurred at regular intervals previously; however, since this was the period in which, as Eric Hobsbawm puts it, “the world became capitalist” (43), the 1857 crisis crystallised the fact that the “malfunctionings of capitalism” are, as Slavoj Žižek states, not “accidental disturbances” but “structurally necessary” (78).

While an increasingly widespread acknowledgement of the inevitability, even, at times, of the desirability, of crises, manifests itself strongly in various representations and discussions of crisis, explanations for these “disturbances” differ widely, and reveal much about the diverse ideological assumptions and expectations of the writers concerned. While Karl Marx, in his articles for The New York Daily Tribune during the period of the crisis and in his correspondence with Friedrich Engels, consistently demonstrates the contradictory and inextricable relationship between expansion and contraction, development and stagnation, most contemporary sources tend to represent the growth of capitalism in terms of progress and of Britain’s superior role on the world stage. Even those writers who acknowledge the human cost of capitalism and crises—the ruthless drive for profits, the restless search for new markets, the growing imbrication of the State and capital—tend to assume a world of amelioration, a universe governed by a natural economic theology of improvement, with capitalism functioning always already as a sustained force for goodness and health, occasionally interrupted by inevitable and inescapable incursions of evil and disaster, existing to be overcome. These writers figure progress at the site where Marx finds contradiction.[2]

This essay will begin by providing an overview of the events of the 1857 crisis and will then describe the key aspects of the Bank Act of 1844. Some crucial contemporary sources will then be examined: section i deals with selections of Marx’s journalism from The New York Daily Tribune and of his correspondence with Engels during the period of the crisis; section ii, with political responses to the suspension of the Bank Act (Disraeli, Gladstone, and Bagehot); and section iii with the subject of speculation and its relationship to crisis (as represented in work by John Stuart Mill and David Morier Evans, as well as selected articles from The Times and The Economist during the period of the crisis). An exploration of these sources lays bare the increasing reification of the prevailing economic, monetary, and social order, and nascent capitalism’s growing relationship with the British State and British imperialism.

The Unfolding of the Crisis

The 1850s are commonly identified as a golden age in Britain—its age of equipoise.[3] The decade is certainly the start of Britain’s great age of capital; Hobsbawm states that never before had British exports grown so rapidly “than in the first seven years of the 1850s” (44) and Sergio Bologna comments that between 1849 and 1858 England’s overseas trade increased by 66 percent (n. pag.). While the export boom that governed the first half of the 1850s was partly the result of the development of new means of travel and communication—the railway, the steamer, and the telegraph—and partly the result of the Palmerston government’s policy of colonial expansion, the role played by money and circulation of money was also crucial. David Landes states that bank credit was a “pillar of the industrial edifice” (75) and Charles Kindleberger comments on the significant role in the great expansion played by joint-stock banks in Britain and ![]() Germany, and the Crédit Mobilier in

Germany, and the Crédit Mobilier in ![]() France, “which loaned strongly to trade and industry” (129). Hobsbawm comments that what made this boom “so satisfactory for profit-hungry businessmen was the combination of cheap capital and a rapid rise in prices” (45). Employment also grew enormously over this period resulting in a period of relative economic and political calm, which was brought to an end by the crisis of 1857.[4]

France, “which loaned strongly to trade and industry” (129). Hobsbawm comments that what made this boom “so satisfactory for profit-hungry businessmen was the combination of cheap capital and a rapid rise in prices” (45). Employment also grew enormously over this period resulting in a period of relative economic and political calm, which was brought to an end by the crisis of 1857.[4]

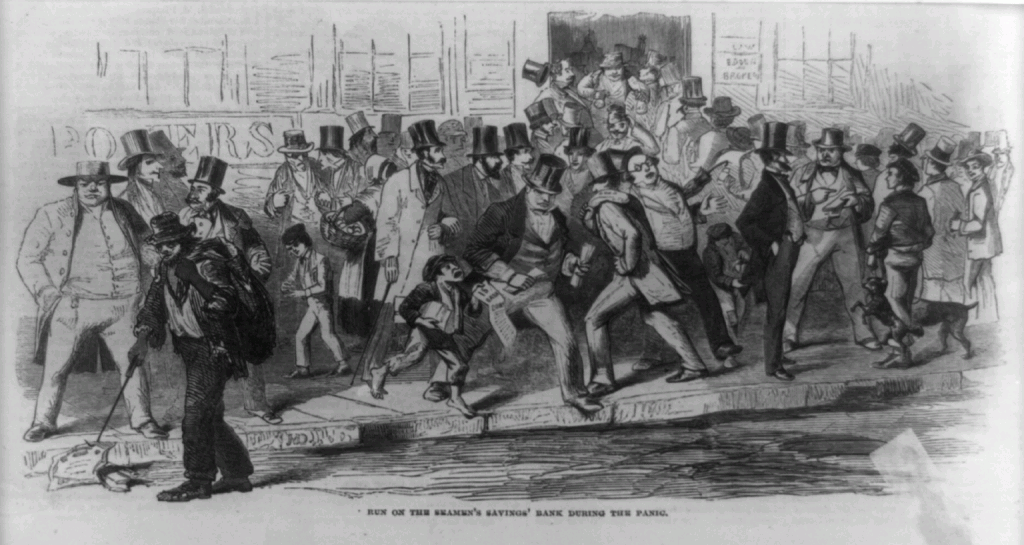

The 1857 financial crisis began very suddenly in the United States with the fall of the Ohio State Life and Trust Company on 24 August 1857, and the panic quickly spread throughout the country, and eventually throughout the world. It is generally regarded as the first world-wide financial crisis (Clapham 226; Hughes 194; J. G Evans 113), spreading not only to England and continental Europe, but as far afield as South America, South Africa, ![]() Australia and the Far East (Clapham 226). David Morier Evans writing in 1859 commented that the crisis was the most “remarkable on record extending as its ravages did through every market and in almost every conceivable direction” (3). Between the 25th and 29th of September, no fewer than one hundred and fifty banks in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Rhode Island suspended specie payment (D. M. Evans 34) and the panic reached a peak in the United States in October when 1,415 banks in the United States failed (J. G. Evans 113).

Australia and the Far East (Clapham 226). David Morier Evans writing in 1859 commented that the crisis was the most “remarkable on record extending as its ravages did through every market and in almost every conceivable direction” (3). Between the 25th and 29th of September, no fewer than one hundred and fifty banks in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Rhode Island suspended specie payment (D. M. Evans 34) and the panic reached a peak in the United States in October when 1,415 banks in the United States failed (J. G. Evans 113).

While England’s economy was deeply embroiled with that of the United States,[5] the panic did not take immediate hold in England. Evans states that the severe depreciation of American securities did not initially cause much anxiety in England and that it was only in October that the price of marketable commodities was generally affected (D. M. Evans 34-5). The repercussions of the events in America were first felt by the two cities most connected with the American trade—![]() Liverpool and

Liverpool and ![]() Glasgow (Morgan 160); during this period, several Glasgow firms failed, and on 27 October, the Liverpool Borough Bank failed. On 7 November, the firm of Dennistoun stopped payment and on 9 November, the Western Bank was suspended. The City of Glasgow Bank did not open on 11 November, and J. H. Clapham points out that by 12 November discounts had almost ceased in London, except at the

Glasgow (Morgan 160); during this period, several Glasgow firms failed, and on 27 October, the Liverpool Borough Bank failed. On 7 November, the firm of Dennistoun stopped payment and on 9 November, the Western Bank was suspended. The City of Glasgow Bank did not open on 11 November, and J. H. Clapham points out that by 12 November discounts had almost ceased in London, except at the ![]() Bank of England (231). Discount rates slowly began to rise. Between 8 – 19 October, they rose from 5½ to 8 per cent. Eight percent was as high as rates had risen during the 1847 crisis, but by the beginning of November 1857, the rate of discount had increased to 9% and by 11 November to 10% (D.M. Evans 34).

Bank of England (231). Discount rates slowly began to rise. Between 8 – 19 October, they rose from 5½ to 8 per cent. Eight percent was as high as rates had risen during the 1847 crisis, but by the beginning of November 1857, the rate of discount had increased to 9% and by 11 November to 10% (D.M. Evans 34).

Bank directors met with Sir George Cornewall Lewis, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, on 10 November to address the crisis. On 12 November, Palmerston, the current Prime Minister, signed the letter that suspended the Bank Charter Act for the second time in ten years. The letter stipulated that the discount rate should go no higher than the 10 per cent at which it stood. Overall, the financial panic began and ended extremely quickly from the Ohio Life failure on 24 August to the suspension of the Bank Act on 12 November in England, to the official end of the crisis on 24 December, with the reduction in Bank Rate from 10% to 8%. While the Bank Act of 1844 had been briefly suspended during the crisis of 1847, the 1857 crisis was the first financial crisis that actually resulted in the violation of the Act, where the Bank of England was actually forced to exceed the statuary limits laid down in 1844. In 1847, the very production of the letter had served to calm the crisis, and the actual necessity to exceed the legal issue of bank notes never arose. In 1857, however, notes for £2,000,000 above the legal limit were issued (J. G. Evans 114).

The suspension and violation of the Act threw into stark relief the defeat of all that the Act had ostensibly set out to remedy. When Sir Robert Peel introduced the Bill to Parliament on 6 May 1844, he stated that he looked forward to “the mitigation or termination of evils, such as those which have at various times afflicted the country in consequence of rapid fluctuations in the amount and value of the medium of exchange.” His speech continued: “I rejoice, on public grounds, in the hope that the wisdom of Parliament will at length devise measures which shall inspire just confidence in the medium of exchange, shall put a check on improvident speculation, and shall ensure, so far as legislation can ensure, the just reward of industry and legitimate profit of commercial enterprise, conducted with integrity and controlled by provident calculation” (qtd. by Economist, 28 November 1857, 1314). The Bill received almost the unanimous support of Parliament (28 November 1857, 1314) and Peel stated on 6 June: “My Confidence is unshaken that we have taken all the Precautions which legislation can prudently take against the Recurrence of a pecuniary Crisis” (qtd. in Kindleberger 173). The ironies of the situation are self-evident. The Bank Act of 1844, that was specifically designed to prevent a recurrence of precisely the kind of crisis it was facing, was suspended in order to calm that very crisis.

The Bank Charter Act of 1844

Sir Robert Peel’s Bank Charter Act of 1844 represented the culmination of the disagreement that existed between the Banking School and the Currency School. The disagreement turned on the question fundamental to capitalist monetary policy, one that continues to be debated to this day, whether it is better to expand the supply of money or to limit it. While both the Banking School and the Currency School believed in the convertibility principle—that is, that notes could be converted into gold upon demand so that there could never be more paper issue than there was gold—they disagreed on the question of the control of circulation.[6] The Banking School, led by James Wilson the founder of The Economist and father-in-law to Walter Bagehot, Joseph Hume a radical politician, and Thomas Tooke, author (in collaboration with William Newmarch) of the monumental six-volume History of Prices, called for the Bank to wield discretionary power as a lender of last resort in order to maintain stability in the money market (Alborn, Cambridge Companion 69). In contrast, the Currency School, led by Samuel Jones Loyd (later Lord Overstone), J. R. McCulloch the Scottish Ricardian, George W. Norman a director of the Bank of England (and close friend of Overstone’s), and the economist Colonel Robert Torrens, argued against discretionary ability to issue paper money, that the supply of money should be limited, and that paper issue had to be confined by the available supply of bullion, and therefore be determined by its fluctuations. Thus banknote circulation should rise only when the stock of bullion rises, not, for example, because interest rates and prices rise.

The Bank Charter Act of 1844 was a triumph for the Currency School. The Act divided the bank into two separate departments—the Banking department and the Issue department. The Issue department was to receive £14,000000, of which the government debt to the bank—of about £11,000,000—was to form a part,[7] and was to be given all the bullion not in current circulation. The Issue department then issued bank notes against these deposits of bullion or coin notes equal to this joint amount minus the number of notes in circulation. Thus the bank could issue notes against securities to the amount of £14,000,000, but could not issue more except against gold or coin.[8] Only the acquisition of more bullion could justify increased issue. The Banking department was to be run like any other bank.[9] The aim of the Act was gradually to coalesce the power of issuing notes exclusively to the Bank of England and to prevent the recurrence of any further crises, such as the one of 1839 when the bank’s stock of gold reserves was severely depleted by the “huge outflow to pay for corn imports” (Edwards 96). That this aim was not even remotely realised was proved by the crisis of only three years later in 1847 and again a decade later in 1857.

Many besides James Wilson warned that the Act could end up precipitating precisely the crises that it was designed to prevent. In Inquiry into the Currency Principle (1844), Thomas Tooke argues that the total separation of the business of issue from that of banking is calculated to produce “greater and more abrupt transitions in the rate of interest, and in the state of credit, than the present system” (n. pag.) and goes on to say that, since the drain of gold most frequently occurs from the taking out of deposits, for example, if there were a run upon the bank, the deposit department could have no recourse to the holdings in the issue department. This could result in a situation where, while the circulating department might remain amply stocked with gold, the “deposit department might have no alternative but to stop payment” (n.pag.). Writing in the first decade of the twentieth century, Andreas Andréadēs also highlights, though rather more indirectly, the contradiction that lies at the heart of the Bank Charter Act. Commenting on the fact that the uneasiness caused by the Act of 1844 “should be allayed by the mere announcement” that the restriction is lifted, he concludes that this is “in itself the best proof of a weakness in the system” (329).

The most unsparing contemporary exposé of the Bank Act, however, is that undertaken by Marx in an article written for The New York Daily Tribune written on 7 November and published as a leader on 21 November 1857. The objection voiced by Tooke—that the Banking and Issue departments could end up working at cross-purposes with one another—is echoed by Marx who foregrounds the identical problem, that the “Banking department might thus become bankrupt” while “bullion were still heaped up in the vaults of the issuing department.” Marx explicates the contradiction he believes underpins the Act, when he points out that since the drain of bullion results in the cancelling of notes, the drain of bullion and the decrease of the reserve of notes “act mutually on each other” so that “the very measures taken to keep up the reserve, tend to exhaust it” (21 November 1857 Collected 380-1). Marx’s scathing analysis of the Bank Charter Act of 1844 is one of a series of pieces that he wrote on money for The New York Daily Tribune. His analyses of the French Crédit Mobilier, of the Bank of England, of the commercial convulsions in England, Continental Europe, and the United States, of the movement of money, and of the speculative nature of the crisis provide a compelling framework for an apprehension not only of the events of the 1857 crisis, but also of the development of mid-century capitalism itself.

i. Marx

From August 1851 to March 1862, Marx worked as a correspondent for the The New York Daily Tribune. While work as a journalist provided Marx with a wide readership and also with the only regular source of income he ever enjoyed (Blitzer xvii), his own financial circumstances were also subject to the fluctuating financial fortunes of the paper.[10] The Tribune‘s growing difficulties began in a circulation war with The New York Times in the early 1850s; in turn, the paper was affected by the 1857 crisis itself.[11] Both advertising and circulation dipped and one of its financial backers went into bankruptcy. This resulted in a reduction in both Marx’s contributions and his pay (Ledbetter xxi). Early in 1857, Marx wrote to Engels saying that he had had “monumentally bad luck” and complaining that the Tribune was not publishing his articles, that the “curs have succeeded in eclipsing the name [he] was making for [him]self among the Yankees” and that he could not continue in such “ruinous” circumstances. His letter continues:

I am utterly at a loss what to do, being, indeed, in a more desperate situation than 5 years ago. I thought I had tasted the bitterest dregs of life. Mais non! And the worst of it is that this is no mere passing crisis. I cannot see how I am to extricate myself.” (20 January 1857 Letters 93-4)

Marx’s impoverished circumstances also left him feeling utterly exploited, trapped by the very capitalist system he was determined to demolish. Three days later, on 23 January 1857, he wrote to Engels again: “To crush up bones, grind them and make them into soup like paupers in workhouse—that’s what the political work to which one is condemned in such large measure in a concern like this boils down to. I am aware I have been an ass in giving these laddies more than their money’s worth—not just recently but for years past” (Letters 98).

Over the ten years of Marx’s employment, however, the Tribune published 487 of his articles.[12] His journalism for the Tribune covered all of the important political and social topics of the day: the Anglo-Chinese conflict, the Crimean War, the British presence in ![]() India, the Indian Revolt, slavery, the Opium trade, the liberation movements and revolutions of the 1840s, and financial developments in Europe and England. In the mid 1850s, however, Marx shifted his attention specifically to banking and the organisation and circulation of money. Bologna points out that, while Engels provided Marx “with a diligent account of the short-time working in the cotton industry and the textile industry in general,” Marx pays very little attention to the working class during the crisis, that Marx focused his attention “entirely on the money-form and the world market.” The banking system, Bologna observes, “becomes the point of departure for Marx’s analysis of the entire bourgeoisie, of aggregate social capital” (n. pag.). Certainly, Marx’s focus in his pieces written for the Tribune on money and the movement of capital is underpinned by his consistent exposure of the contradictions that he finds at the heart of capitalism and on the ways in which it is represented and investigated during the course of the financial crisis.

India, the Indian Revolt, slavery, the Opium trade, the liberation movements and revolutions of the 1840s, and financial developments in Europe and England. In the mid 1850s, however, Marx shifted his attention specifically to banking and the organisation and circulation of money. Bologna points out that, while Engels provided Marx “with a diligent account of the short-time working in the cotton industry and the textile industry in general,” Marx pays very little attention to the working class during the crisis, that Marx focused his attention “entirely on the money-form and the world market.” The banking system, Bologna observes, “becomes the point of departure for Marx’s analysis of the entire bourgeoisie, of aggregate social capital” (n. pag.). Certainly, Marx’s focus in his pieces written for the Tribune on money and the movement of capital is underpinned by his consistent exposure of the contradictions that he finds at the heart of capitalism and on the ways in which it is represented and investigated during the course of the financial crisis.

Marx’s 21 November denunciation of the Bank Charter Act, mentioned above, is based on extensive concrete material and monetary details pertaining to the Act: the specific nature of the reserve and bullion available; the reports of the Bank of England from 1847 to 1857; a comparison of the number of notes that actually circulated from 1819 until 1847. His exposé, however also details the more subtle, wide-ranging implications of the Act, which affected “not only England, but also the United States, and the whole market of the world” (Collected 379). Marx foregrounds the ineluctable relationship between politics, power, and money as he comments on the close relationship between the Government and the Bank that led to the creation of the Act in the first place by Sir Robert Peel backed by the banker Loyd, now Lord Overstone. The Bank Act, for Marx, is corruption and self-interest disguised as policy, its “only advantage” being that the “whole community is placed in a thorough dependence on an aristocratic Government” (Collected 382). Such a dependence, for Marx, explains the “Ministerial predilections for the act of 1844,” since it invests them “with an influence on private fortunes they were never before possessed of.” Further, Marx comments on the manufactured, almost fictive aspect of the panic, which he sees as “artificially” aggravated and accelerated, and, finally, he mocks the fallacies propounded by Britain’s economists who “when the first news of the American crisis reached the shores of England” claimed English trade to be “sound,” but its “customers, and above all, the Yankees” to be “unsound” (Collected 382-3). Thus, even as Marx summarises the futility of the Act, which “does not act at all in common times; adds in difficult times a monetary panic created by law to the monetary panic resulting from the commercial crisis; and, at the very moment when, according to its principles, its beneficial effects should set in, it must be suspended by Government interference” (Collected 381-2), he uncovers the ideological frameworks that hide the contradictions at the heart not only of the Act, but of the capitalist system that underpins it. Certainly, Britain’s inviolable belief in its own superiority over, and separateness from, its more apparently fallible neighbours and trading partners permeates contemporaneous discussions of the crisis; indeed, three weeks later Marx foregrounds the unreliability of the commentary in The Times, which having consistently announced the “‘soundness’ of British commerce as its theme, now declares ‘the trading classes of England to be unsound to the core’” (15 December 1857, Collected 400).[13] Thus, while Marx focuses in great detail on the relationship between the crisis and the circulation of money, he uses such detail to expose the political institutions whose very existence depends on the ways in which money is circulated and credit is issued.

This exposure of political interests emerges extremely clearly in a letter to Engels (8 December 1857) where he discusses not only Overstone’s “true” reason of his “fanatical” advocacy of the Act (extraordinary profits), but also the ways in which the Act has been dealt with by the Press, and the relationship between the financial and the industrial crisis:

I’ve had a gratifying experience with the Tribune. On 6 November I wrote an exposé for them of the 1844 Bank Act, in which I said that the next few days would see the farce of suspension, but that not too much should be made of this monetary panic, the real affaire being the impending industrial crash. The Tribune published this as a leader 3 days later. The New-York Times (which has entered into a feudal relationship with the London Times replied to the Tribune to the effect that, firstly, the Bank Act would not be suspended, extolled the Act after the manner of the money-article writers of Printing House Square, and declared the talk of an ‘industrial crash’ in England to be ‘simply absurd’. This was on the 24th. The following day the N.Y.T. received a telegram from the Atlantic with the news that the Bank Act had been suspended, and likewise news of ‘industrial distress’. It’s nice, by the by, to see Loyd-Overstone coming out with the true reason for his fanatical advocacy of the 1844 legislation — because it permitted the ‘hard calculators’ to squeeze 20-30% out of the commercial world. (Letters 215)

Marx’s references to the industrial distress (avoided by the mainstream press) in this letter to Engels echoes his comments published in the Tribune on 30 November 1857, where he identifies three distinct forms of the British crisis: pressure on the money and produce markets (in London and Liverpool), a banking panic (in ![]() Scotland), and an industrial breakdown (in the manufacturing districts). He analyzes each of these areas in turn. After examining the fluctuations of interest rates over the previous ten years, he predicts that the crisis, which he sees as having been due since 1855 and avoided only by the influx of gold from Australia and California, “will exceed every crisis ever before witnessed” (387). His consideration of the Banking crisis leads him to similar conclusions to those reached in his article of 21 November, and he then turns his attention to the manufacturing sector, citing an extract from a private letter from

Scotland), and an industrial breakdown (in the manufacturing districts). He analyzes each of these areas in turn. After examining the fluctuations of interest rates over the previous ten years, he predicts that the crisis, which he sees as having been due since 1855 and avoided only by the influx of gold from Australia and California, “will exceed every crisis ever before witnessed” (387). His consideration of the Banking crisis leads him to similar conclusions to those reached in his article of 21 November, and he then turns his attention to the manufacturing sector, citing an extract from a private letter from ![]() Macclesfield in The London Free Press:

Macclesfield in The London Free Press:

At least 5,000 persons, consisting of skilled artisans and their families, who get up each morning and know not where to get food to break their fast, have applied for relief to the Union, and as they come under the class of able-bodied paupers, the alternative is of either going to break stones at about four pence per day, or going into the house, where they are treated like prisoners, and where unhealthy and scanty food is given to them through a hole in the wall; and as to the breaking of stones, to men that have hands only capable of handling the finest of materials, viz: silk, [that], is a complete refusal. (Collected 390)

“The present convulsion,” Marx continues, “bears the character of an industrial crisis, and therefore strikes at the very roots of the national prosperity” (Collected 390). Marx focuses here on aspects of the crisis that he regards as being eschewed by the prevarications and denials of the press; indeed, towards the end of his 8 December letter to Engels discussed above, he states: “Your information about conditions in ![]() Manchester is of the greatest interest to me, the newspapers having chosen to draw a veil over them” (Letters 216). Two months later he comments in the Tribune that “at the present moment the industrial crisis rages most violently in the British Woolen districts, where failure follows upon failure, anxiously concealed from the general public by the London press” (3 February 1858, Collected 427).

Manchester is of the greatest interest to me, the newspapers having chosen to draw a veil over them” (Letters 216). Two months later he comments in the Tribune that “at the present moment the industrial crisis rages most violently in the British Woolen districts, where failure follows upon failure, anxiously concealed from the general public by the London press” (3 February 1858, Collected 427).

But what emerges most strongly in Marx’s money articles of the period is his theorization of the capitalist mode of production that both engendered and perpetuated the crisis. In a piece published 26 January 1855, almost three years before the crisis of 1857, Marx not only predicts the crisis, but mocks the consistent insistence on the part of the trading classes that the crisis must “proceed from accidental and exceptional circumstances.” The “professional free-traders of Great Britain,” Marx points out, now wish to blame the War in Crimea for current commercial difficulties, refusing to acknowledge that the present crisis flows “from the natural working of the modern English system,” and is “altogether akin to the crises experienced at periodic intervals almost since the end of the 18th century” (Dispatches 166-67). Marx, citing from a number of commercial circulars all pertaining to the problems created by overproduction, provides compelling reasons for his argument that the current crises in both England and America “may be traced to the same sources–the fatal working of the English industrial system which leads to over-production in Great Britain, and to over speculation in other countries” (Dispatches 170). Similarly, in an article published on 4 October 1858 on the Report on the Crisis of 1857-58 of the Committee appointed by the House of Commons, Marx writes a scathing critique of the conclusions reached by the Committee—that the crisis was ‘mainly owing to excessive speculation and abuse of credit.’[14] Such a conclusion does not solve what Marx calls the “social problem,” and while Marx does not disagree with the fact that over speculation played a large role in the crisis, he regards it as a symptom rather than a cause (Dispatches 200-01). Thus, in response to the central question that he poses—“What were the real causes of the crisis?”—he finds the answer in the very nature of capitalism itself. For “a system of fictitious credit to spring up,” he states, “two parties are always requisite—borrowers and lenders.” The question that should be asked is

how it happens that, among all modern industrial nations, people are caught, as it were, by a periodical fit of parting with their property upon the most transparent delusions […]. What are the social circumstances reproducing, almost regularly, these seasons of general self-delusion, of over-speculation and fictitious credit? If they were once traced out, we should arrive at a very plain alternative. Either they may be controlled by society, or they are inherent in the present system of production. In the first case, society may avert crises; in the second, so long as the system lasts, they must be borne with, like the natural changes of the seasons. (Tribune, Dispatches 200-01)

Thus, Marx outlines the ineluctable pattern inherent in capitalism: inevitable and inescapable crises that are central to its very formation and progression, and that are, therefore, by their very nature, not controllable by society. Capitalism is the crisis; inherent in the very idea of development is the expansion that can only result in ultimate contraction. As Bologna explains it, “The causes of crisis are the causes of development; they are intrinsically necessary to capitalist development” (n. pag., original emphasis). It is this cycle that Žižek refers to as the “self-blinding ‘irrationality’” that is capitalism—a “pressure, an inner drive to go on, to expand the sphere of circulation in order to keep the machinery running, inscribed into the very system of capitalist relations” (36-7).

But while Marx finds a fundamental contradiction at the core of capitalism—that development and its destruction are inextricably connected with each other—representations of the crisis provide what Bologna terms a “pathogenic” view of the crisis, a view that treats the crisis as a “result of errors on the part of the capitalist class—failures of calculation, inability to plan the economy on the part of capital” (n. pag., original emphasis). All of the writers and representations discussed below do approach the crisis from Bologna’s “pathogenic” viewpoint in that their explanations and solutions rely on normative assumptions about capitalist relationships and modes of production. Thus, although these analysts of the Bank Act and the 1857 crisis might be in profound disagreement with one another, their teleological assumptions in relation to the ameliorative effects of capitalism are extremely similar.

ii. Politics and the Bank: Disraeli, Gladstone, Bagehot

The concerns that Marx foregrounds in his critique of the Bank Act—its susceptibility to suspension, its potential for corruption, its legitimation of uneven distribution of power and of undue influence—are, paradoxically enough, echoed (although obliquely) in the parliamentary responses of Benjamin Disraeli and William Ewart Gladstone to the crisis and to the suspension of the Bank Act. They too focus on the futility of the Act in the light of its vulnerability to suspension, the political status of the Bank, and the complexities surrounding discretionary power and who has it. Disraeli and Gladstone, both belonging to the highest echelons of power so reviled by Marx in his discussion of the Act, clearly seek different solutions than Marx does to the problems engendered by both the Bank Act and the crisis (and, indeed, from each other). Nevertheless, both men foreground, as Marx does, the political implications underpinning the suspension of the Act. Timothy Alborn points out that what the Bank Act had done in the first place in limiting the Bank’s “discretionary ability to issue paper money” is to add to “a growing perception that the Bank had largely ceased to be a political company” (Conceiving 55). The responses of both Disraeli and Gladstone to the suspension highlight the political function of the bank in both its lending and its issuing capacities.

Disraeli’s response to the crisis and the suspension of the Bank Act mirrors the fundamental position held by the Banking School; he regards the Act as moribund and calls for discretionary power to be vested in the Bank directors. The continual suspension of the Act, for Disraeli, has undermined both its effectiveness and its morality. Asking what the point is of “allowing the currency of this country to be regulated by an Act which we are in a continual state of being prepared to suspend” (“Bank Issues Indemnity Bill” Hansard 148: 217), he goes on to conclude that “the moral influence which all laws ought to possess is, so far as this statute is concerned, absolutely dead” (“Select Committee Moved” Hansard 148: 607-8). In the absence of the “moral influence” of the law, Disraeli calls for control to be returned to the Bank and vested in the discretionary power of its Directors, investing the Bank Directors with the moral influence he believes the law to have lost: “the Directors of the Bank of England have a great duty to perform to the nation as well as to themselves. […] It is in the regulation of their rate of discount, it is in the discrimination and discretion with which advances are made by the Directors of the Bank, that a beneficial influence may indeed be exercised over the fortunes of this country” (“Select” 148: 629). Disraeli’s belief in the connection between rates of discount, advances, and serving the country is quite overt; economic duty, political duty, and moral duty are entirely consonant with each other.

Disraeli’s wish to enhance the political and moral power of the Bank by investing it with discriminatory powers was staunchly opposed by Gladstone. Gladstone, like Disraeli, also details the absurdity of a law that requires suspension each time trouble arises, but the two men disagree fundamentally about the solutions to the problem.[15] Gladstone rejects what he calls the “antiquarian” relationship between the Government and the Bank, stating that it is foreign to “English habits, ideas, and traditions” that “such a discretion of determining the ruin of one man and the preservation of another should be vested in the Ministers of the Crown” (“Select” 148: 648). The solution he proposes is to separate entirely the issue department from the lending department; the removal of note issue from the purvey of the Bank would result in a reduction of its political power. “Let us, above all, effect by law that separation of the functions of issue and of banking which will relieve the Bank of England from a false position in regard to the commerce of the country when crises occur,” he states (“Select” 148:653). Alborn points out that in Gladstone’s attempt to depoliticize the bank by eliminating the Bank’s political function as note issuer, he urges “the same sort of nationalized note-issuing department that Ricardo had supported forty years earlier” (Conceiving 73). Both Gladstone and Disraeli highlight the political implications of the Bank Act and its suspension, although arrive at diametrically opposed solutions. Where Disraeli sees the return of moral duty in placing power in the hands of the Bank and allowing it to exercise its “beneficial influence” on the country, Gladstone wishes to “relieve the Bank of England from its false position” vis á vis the country, ostensibly thereby restoring to it its integrity.

Writing in the National Review in January 1858 in an essay entitled “The Monetary Crisis of 1857,” Walter Bagehot responds sharply to Gladstone’s call to remove power from the Bank:

Some statesmen have fancied they can elude the difficulty by carrying further the essential principle of the Act of 1844, vesting the business of issue in a Government department altogether and geographically separate from the Bank of England. (Collected X: 70)

Bagehot rejects Gladstone’s proposal, stating that geographical separation would have done little to mitigate the crisis, that whatever the change in form, the “Government would have done exactly what they have now done” (70). Indeed, discretionary power for Bagehot is intrinsic to the management of any system, and in response to Gladstone’s desire to eschew governmental responsibility for the success or collapse of various companies, Bagehot regards the responsibility as unavoidable: “in actual practice,” he argues, “the discretionary employment of such an expansive power as is proposed does of necessity involve their having to decide such points” (Collected X: 73).

Bagehot’s analysis of the crisis and the suspension of the Bank Act engenders his call to re-politicize the Bank, invest greater discretionary powers in the hands of the Bank Directors, and increase the Bank reserve. For Bagehot, the Bank of England already possesses an “unnatural supremacy” (55), a predominance that is essentially immutable since it is the result of tradition, history, and habit. In the light of these historical circumstances, in light of the fact that it is “the only actual cash reserve for all the banking liabilities of the country,” and in light of the “dangerously low” reserve held by the Bank in the period leading up to and during the crisis, Bagehot concludes that the only safe solution for surviving crises is an increased reserve; by keeping “a much larger reserve in times of security, the Bank may retain the power of making these sudden and large advances in times of insecurity” (60-1). While Bagehot acknowledges problems of trust and confidence to be an inevitable by-product of enhanced discretionary power, he considers the rigidity that results from the absence of discretion to be the worse evil. While discretionary power inevitably involves “the necessity of intrusting our entire bullion reserve to the discretion of the Bank directors” (69), Bagehot nevertheless holds that it is the Bank directors who “ought to regulate, and ought to be responsible for, all the acts of the Bank, whether legal or extra-legal” (73). He concludes: it “may be an evil to have discretion; but the event of the last few months prove […] the evils of a rigid rule which admits of no discretion” (75). Thus while Bagehot is in agreement with both Gladstone and Disraeli about the Bank Act having aggravated the “seriousness into apprehension, and apprehension into terror” (65), he finds a solution in an increased discretionary power of the Bank, and in the keeping of a larger reserve.[16]

As with Gladstone and Disraeli, Bagehot’s analysis is also framed by jingoist assumptions about Britain’s role on the world stage. In this same essay, he proudly describes the fitness of the English character (as he sees it) for capitalist enterprise:

A certain energy of enterprise is the life of England. Our buoyant temperament drives us into action; our firm judgment makes us steady in real danger; our solid courage is inapprehensive of fanciful risk. […] Accordingly our commercial men have for years been prone to great undertakings; possibly there may not be in the world at this moment a single large and adventurous speculation in which there is not some sum of Anglo-Saxon capital. (“Monetary” 53)

Moral courage and judgement are thoroughly entwined with financial risk, enterprise, and speculation. Alborn points out that Bagehot’s proposal for a larger Bank reserve met with the kind of success that it did because he reached these suggestions from “evolutionary premises,” which “strengthened their influence on public opinion, which in the late Victorian era tended to be well disposed to theories of progress that placed Britain atop the heap of ‘civilization’” (Conceiving 77). The following section examines diverse responses to the question of “large and adventurous speculation.” While writers such as Mill and Evans are compelling on the subject of the costs of crisis and speculation (and, in the case of Mill, at times, even capitalism itself), representations of the crisis in The Times and The Economist reveal fundamental connections between the functioning of capitalism and patriotic pride.

iii. Speculation and Reification: John Stuart Mill; David Morier Evans: The Times; The Economist

In an article written 15 December 1857, Marx adumbrates the analyses of those who seek the causes of the crash in the “recklessness of single individuals”:

If speculation toward the close of a given commercial period appears as the forerunner of the crash, it should not be forgotten that speculation itself was engendered in the previous phases of the period, and is therefore, itself a result and an accident, instead of the final cause and substance.

He continues: “The political economists who pretend to explain the regular spasms of industry and commerce by speculation, resemble the now extinct school of natural philosophers who considered fever as the true cause of maladies” (Collected 400-03). Marx’s wry analogy not only encapsulates the fallaciousness of the arguments of those analysts of the crisis that insistently confuse symptom and cause, but also lays bare the false oppositions that might underpin such analyses in the first place. The crisis for Marx cannot be figured as a “malady” (with hopes of cure) since the entire operating system carries the disease. Žižek, in a similar vein, points out that speculation cannot be particularly separated from any other phase of capitalist enterprise, stating that “the very dynamic of capitalism blurs the frontier between ‘legitimate’ investment and ‘wild’ speculation, because capitalist investment is, at its very core, a risky wager that a scheme will turn out to be profitable, an act of borrowing from the future” (36).

Nevertheless, over-speculation is frequently depicted as an underside of evil, blight, and disaster in a normally profitable system. Even writers who perceive a value in crises (such as John Stuart Mill and David Morier Evans) revile the behavior of ruthless speculators that precipitated the crisis in the first place. David Morier Evans’s meticulously researched, wide-ranging account of the crisis and its aftermath in History of the Commercial Crisis, written in 1859, demonstrates a complex relationship of the cyclical patterns of panics and prosperity. While, on the one hand, Evans reviles the greed, the voracity, and the immorality of the speculators whom he regards as having precipitated this crisis, on the other, he also treats crises as necessary scourges that cleanse and reform.[17] This doubled appraisal of the crisis permeates his History.

Evans begins his History by detailing the major, preceding panics of the nineteenth century. In spite of individual distinguishing features, they resemble each other “in occurring immediately after a period of apparent prosperity, the hollowness of which [each crisis] has exposed” (1). For the 1857 panic, the “hollowness” at the core of prosperity was the consequence of the “low state to which commercial morality had sunk” and the “utter rottenness” of the commercial system; England and ![]() New York appeared to be “vying with each other in bare-faced fraud” (11). Paradoxically, however, in spite of his moral disapprobation, Evans also treats the crisis as a necessary evil, whose function it is both to expose and redeem. The “evil of a panic is not altogether unmitigated,” he states, since the commercial atmosphere is “cleared by the explosion of a number of establishments that have existed on a false basis.” Evans’s metaphor of an explosion encapsulates a crucial element of crisis for Evans: its violence, but also its capacity to purify and cleanse. Panics therefore possess an ameliorative function where “[w]rong principles” are “exposed”; perpetrators are “checked in their power of producing mischief” and “the necessity of a reform in a state of laws under which such vast evils have been allowed to flourish” is rendered apparent (10-11).

New York appeared to be “vying with each other in bare-faced fraud” (11). Paradoxically, however, in spite of his moral disapprobation, Evans also treats the crisis as a necessary evil, whose function it is both to expose and redeem. The “evil of a panic is not altogether unmitigated,” he states, since the commercial atmosphere is “cleared by the explosion of a number of establishments that have existed on a false basis.” Evans’s metaphor of an explosion encapsulates a crucial element of crisis for Evans: its violence, but also its capacity to purify and cleanse. Panics therefore possess an ameliorative function where “[w]rong principles” are “exposed”; perpetrators are “checked in their power of producing mischief” and “the necessity of a reform in a state of laws under which such vast evils have been allowed to flourish” is rendered apparent (10-11).

Nevertheless, in spite of the ameliorative function of crisis, Evans frequently explicates the 1857 crisis in the language of temptation, sin, corruption, evil, and greed. The vast resources suddenly available, Evans says, afforded “temptation” to the “worst kind of commercial gambling” creating a “throng of greedy speculators anxious to work the credit system”; in lenders “utter recklessness,” in borrowers “unparalleled avidity” (33). Such evil perpetrates terrible consequences and the History is filled with careful historical detail about the wretchedness and misery proliferated by the crisis. Evans details what he describes as “all the paraphernalia of distress”: the records of “town after town” that “treat of wholesale cases of destitution,” meetings to “petition poor-law guardians, charitable assistance in the shape of soup-kitchens, forced labour in public works” (37). The suffering he perceives all around him is a result of “fraud,” “recklessness,” a “rotten system of accommodation,” or “vice” (37-8). “Never did wickedness and commerce seem so intimately allied as during the great panic of 1857,” he declares; the evil “spread like a pestilence” (11).

Evans’s doubled relationship with crises is also to be found in the writings of John Stuart Mill, who at times appears extremely ambivalent not only about crises, but also about capitalism itself. In chapter IV of Principles of Political Economy (1848), Mill emphasizes the necessity, even the desirability, of crisis. Crisis, for Mill, “arrests profits in their descent to the minimum, by sweeping away from time to time a part of the accumulated mass by which they are forced down.” A crisis functions as a “counteracting principle” in order to avoid the “stationary condition of capital” that must inevitably occur if accumulation continues uninterrupted (734-5). Furthermore, in finding that in spite of periodic crises, England’s capital continues to increase, Mill argues against the very notion of the destructiveness of crises since “each commercial revulsion, however disastrous, is very far from destroying all the capital which has been added to the accumulations of the country since the last revulsion preceding it” (734-5).[18] Mill’s “sweep” appears to have the same overtones as Evans’s “explosion” with both metaphors evincing the idea of cleansing and starting anew.

Nevertheless, in spite of what appears to be a rather lofty acceptance of crises and the costs attendant upon them, Mill is also concerned with what he terms in his Autobiography (written twenty-five years after the Principles), the “human element.” This human element is ascribed in the Autobiography to the immense intellectual and emotional influence of Harriet Taylor on his life, where Mill describes what “was abstract and purely scientific” as belonging to him and the “properly human element” as coming from her (159). The human element certainly manifests itself in the chapter, “Of the Stationary State,” in the Principles, where Mill appears to counter his own stated ideas about crisis formulated earlier in the text, including the very notion that the stationary state is to be avoided if possible. Framed by questions relating to human and social welfare, Mill states that he cannot regard the stationary state with the “unaffected aversion so generally manifested towards it by the political economists of the old school.” Indeed, he goes on to state that he is “not charmed” by those who think “the normal state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other’s heels […] are the most desirable lot of human kind,” and that the stationary state might therefore be a “considerable improvement on our present condition” (748). Mill reviles the human cost of the crisis, and questions the basic tenets of capitalism itself, when he comments on the “life of drudgery and imprisonment” (749) led by the greater population, and seeks “better distribution” and limitations upon inheritance (751). Pronouncing his indifference to the “mere increase of production and accumulation,” Mill illuminates the inherent destructiveness for humankind of the ruthless drive for profits, and the desperate thrust for expansion (749).

Both Mill and Evans explicate the ostensible necessity of crisis, but they simultaneously illuminate its terrible human cost. In contrast, the coverage of the crisis and the suspension of the Bank Act in the Times and the Economist are framed by jingoism, progress, and national pride.

The Times emerges as a firm defender of the Bank Act, the corollary of which is that, in the weeks leading up to the crisis, it consistently announces that there is no cause for concern. The Act is repeatedly defended in terms of economic health and well-being and national pride. On 13 October 1857 after the news of the American crisis has broken, The Times writes that there is “nothing to excite apprehension that the disturbance will be protracted,” continuing: “altogether the feeling exhibited was such as to excite pride in our healthful system of finance […] [T]his shock from America […] shall not destroy confidence or interrupt the general welfare of the country” (4). On 6 November, The Times, having announced derisively that the “old opponents of the Bank Charter Act […] are beginning to bustle in the storm,” goes on to state that there is “not the slightest provocation to panic, and whether such a humiliating exhibition of national ignorance and folly can now take place is a question rational people would hardly have entertained a few weeks back.” The article concludes that there is “not the shadow of a pretext for any cry for government palliatives” (4). The arguments throughout are based on appeals to national pride rather than on rational financial analyses. Patrick Brantlinger points out that the “fetishizing of the economy […] parallels the fetishizing of the state through the dual ideologies of nationalism and imperialism” (125); certainly in The Times’ depiction of the crisis, the two systems cannot be separated. Should the nation “so pitiably lose its self-possession as to give way to panic, there is but one remedy,” The Times states, but goes on to say that it is not necessary to proclaim a belief that the “financial sense of the nation is still so low as to cause the degrading contingency to be regarded” (4).

When the disavowed contingency does come to pass, it is blamed on greedy speculators. On 17 November, five days after the suspension of the Act, M. B. Sampson, still defending the Act, asks “whether it is not through the conviction on the part of fraudulent traders and reckless money lenders that this tampering will always be resorted to throw the consequences of their own misconduct upon the country” and that Parliament shall decide whether the law should be modified to enable those who for their “sordid purposes supply capital to adventurers” (4).[19] Similarly, on 26 November, The Times proclaims that it is a result of “calling into existence gangs of reckless speculators and fictitious bill drawers, and elevating them as examples of successful British enterprise, so as to discourage reliance upon the low profits of honest industry, that a poison is infused” (7). The idea of adventurers, gamblers, and fortune-hunters functioning as toxic contaminants of an honest, healthy British system allows for the avoidance of any interrogation of the capitalist system itself. The economy is reified, as Brantlinger points out, as a “realm of seemingly natural ‘laws,’ more or less divorced from the processes of political criticism, decision making, and reform or revolution that could change those practices and theories” (125). In such a system of representation, economic theories and practices are allowed to remain entirely intact, undisturbed by facts or events that might give lie to the whole.

The Economist, a staunch opponent of the Bank Act from the outset, under the aegis of its editor, James Wilson, sought a broader explanation for the cause of the crisis than the issue of bank notes, excessive or otherwise. Nevertheless, it too ultimately falls back on the horrors of speculation as a final explanation for the crisis. Much of its coverage during the early weeks of the crisis is devoted to analyses of the crucial errors that underpinned the very principles on which the Bank Act was founded in the first place, and their deleterious consequences. The leader of 14 November 1857 on the Suspension of the Bank Act (published two days after the suspension) states that the Act was suspended “just in time to save a national calamity and the irretrievable destruction of many private fortunes” (“Suspension” 1257) and on 21 November that “no-one can, therefore, deny that when a pressure does arrive, the fact of the existence of this arbitrary limit does materially aggravate the difficulty of the crisis, by increasing it into panic” (“Suspension” 1287). Again on 28 November, arguing against a “certain class of doctrinaires” who “refer every commercial crisis and its disastrous consequences to ‘excessive issue of bank notes’” (“Crisis” 1312), the magazine provides a detailed analysis of the various banks that failed from New York to Liverpool to Scotland proving that none of these failures was due to the excessive issue of notes.[20]

Nevertheless, even The Economist traces the root of the crisis to over-speculation. On 28 November, it states: “It would indeed be difficult to use words too strong condemnatory of the loose and reckless credit system which has prevailed in the American trade” (sic “Suspension” 1314) and on 5 December, in a piece entitled “the Deeper Causes of the Recent Pressure,” the writer, having refuted the arguments of the Currency School, finds the crisis to be “the offspring of a state of things in which speculation and expenditure had become inordinate and excessive, in consequence of some real or assumed increase in the incomes and resources of the trading and general community” (1344-5). On 26 December, outraged jingoism and moralism frame an analysis of President James Buchanan’s address to Congress on the subject of the late monetary crisis: “in place of probing the evil to its root, and undertaking the unpopular task of exposing the unsound and rotten speculations which have constructed into huge engines for extracting capital from other countries,” Buchanan, the magazine claims, prefers to dwell “upon the old theme” of ‘extravagant and vicious systems of paper currency and Bank credits’” thereby “screening the real delinquents who have perpetrated so much mischief.” For The Economist, diverting attention to the banks and paper currency obscures “the real cause of the evil”: “the wildest speculations and the most fraudulent transactions” which have been “constantly hid from public observation” (“American President” 1425-6).

The representations of the 1857 crisis discussed above represent an array of economic and political possibilities. Marx and Engels saw in the 1857 crisis the potential for the start of the Revolution. Anticipating the crisis almost a year before it occurred, Engels writes to Marx that “This time there’ll be a dies irae [day of wrath] such as has never been seen before” (not before 27 September 1856, Letters 72), and after the onset of the crisis, he writes: “Never again, perhaps, will the revolution find such a fine tabula rasa as now” (17 November 1856 Letters 83). The expectations of Marx and Engels, however, were not met. The 1857 crisis was short-lived, as Hobsbawm states, “merely an interruption of the golden era of capitalist growth” (46). Capitalism remained the order of the day, the essential base for England’s wealth, and expansion. Ultimately, the mid-1850s bore witness to the growing fetishization and reification of the economic order, which took on a life of its own.

published March 2015

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Shakinovsky, Lynn. “The 1857 Financial Crisis and the Suspension of the 1844 Bank Act.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Alborn, Timothy L. Conceiving Companies: Joint Stock Politics in Victorian England. London & New York: Routledge. 1998. Print.

—. “Economics and Business.” The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Culture. Ed. Francis O’ Gorman. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010. 61-79. Print.

“The American President on the American Crisis.” The Economist 26 December 1857: 1425-27. Microfilm.

Andréadēs, Andreas Michael. History of the Bank of England: 1640-1903. 1909. Trans. Christabel Meredith. New Introduction by Paul Einzig. 4th ed. London: Frank Cass, 1966. Print.

Bagehot, Walter “The Insufficiency of the Bank Reserve Aggravated by Sir Robert Peel’s Act.” The Collected Works of Walter Bagehot. Ed. Norman St. John-Stevas. London: The Economist, 1978. IX: 378-80. Print.

—. “The Monetary Crisis of 1857.” The Collected Works of Walter Bagehot. Ed. Norman St. John-Stevas. London: The Economist, 1978. X: 49-80. Print.

—. “On the Insufficiency of the Bank Reserve.” The Collected Works of Walter Bagehot. Ed. Norman St. John-Stevas. London: The Economist, 1978. IX: 370-77. Print.

“Bank Issues Indemnity Bill.” Hansard 1803-1905. UK Parliament. House of Commons. Debates. 4 December 1857. Vol. 148 cc145-226. Web. 30 October 2014. <http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1857/dec/04/bank-issues-indemnity-bill>.

Blitzer, Charles. “Introduction.” The American Journalism of Karl Marx: A Selection from Henry M. Christman. New York: The New American Library, 1966. vii-xxx. Print.

Bologna, Sergio, “Money and Crisis: Marx as Correspondent of the New York Daily Tribune, 1856-57.” Trans. Ed. Emery. Wildcat. n.p, n.d. Web. 22 August 2014. <http://www.wildcat-www.de/en/material/cs13bolo.htm>.

Brantlinger, Patrick. Fictions of State: Culture and Credit in Britain 1694-1994. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1996. Print.

Burn, W. L. The Age of Equipoise: A Study of the Mid-Victorian Generation. London: Allen & Unwin, 1964. Print.

Checkland. S. G. The Rise of Industrial Society in England: 1815-1885. London: Longman, 1964. Print.

Clapham, J. H. The Bank of England: A History. Vol. II, 1797-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1944. Print.

“The Crisis and the Currency: The Act of 1844.” The Economist 28 November 1857: 1313-15. Microfilm.

The Deeper Causes of the Recent Pressure.” The Economist 5 December 1857: 1312-15. Microfilm.

Edwards, Ruth Dudley. The Pursuit of Reason: The Economist 1843-1893. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1993. Print.

Evans, D. Morier. The History of the Commercial Crisis 1857-1858 and the Stock Exchange Panic of 1859. 1859. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1969. Print.

Evans, John Guiseppe. The Bank of England: A History from its Foundation in 1694. London: Evans Brothers Limited, 1966. Print.

Hewitt, Martin. Ed. An Age of Equipoise?: Reassessing Mid-Victorian Britain. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000. Print.

Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Capital: 1848-75. London: Abacus, 1997. Print.

Houston, Gail Turley. From Dickens to Dracula: Gothic, Economics, and Victorian Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005. Print.

Hughes, J. R. T. “The Commercial Crisis of 1857.” Oxford Economic Papers 8: 2 (June 1956): 194-222. Web. 02 April 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2661732.

Kempton, Murray. “K. Marx, Reporter.” New York Review of Books. New York Review of Books, 15 June 1967. Web. 12 September 2014.

Kim, Kyun. Equilibrium Business Cycle Theory in Historical Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988. Print.

Kindleberger, Charles P. Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. New York: Basic Books, 1978. Print.

Landes, David S. The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Ledbetter, James. “Introduction.” Dispatches for the New York Tribune: Selected Journalism of Karl Marx. Ed. James Ledbetter. New York: Penguin, 2007. xvii-xxvii. Print.

Marx, Karl. “The Bank Act of 1844 and the Monetary Crisis in England.” New York Daily Tribune 21 November 1867 in Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Collected Works May 1856 – September 1858. Vol. 15. London: Lawrence & Wishart; New York: International Publishers; Moscow: Institute of Marxism-Leninism, 1986. 379-84. Print.

—. “British Commerce.” New York Daily Tribune 3 February 1858 in Marx, Engels. Vol. 15. 425-34. Print.

—. “British Commerce and Finance.” New York Daily Tribune 4 October 1858 in Dispatches for The New York Tribune: Selected Journalism of Karl Marx. Ed. James Ledbetter. New York: Penguin, 2007. 200-04. Print.

—. “The British Revulsion.” New York Daily Tribune 30 November 1857 in Marx, Engels. Vol. 15. 385-91. Print.

—. “The Commercial Crisis in Britain.” New York Daily Tribune 26 January 1855 in Dispatches for the New York Tribune: Selected Journalism of Karl Marx. Ed. James Ledbetter. New York: Penguin, 2007. 166-69. Print.

—. “The Trade Crisis in England.” New York Daily Tribune 15 December 1857 in Marx, Engels. Vol. 15. 400-403. Print.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Collected Works: Letters. Vol. 40. London: Lawrence & Wishart; New York: International Publishers; Moscow: Institute of Marxism-Leninism, 1983. Print.

Mill J. S. Autobiography. New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1909. Print.

—. Principles of Political Economy, with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy. Ed. Sir William Ashley. London: Augustus M. Kelley Publishers, 1965. Print.

“Money-Market and City Intelligence.” Times [London, England] 13 Oct. 1857: 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 18 July 2014.

“Money-Market and City Intelligence.” Times [London, England] 6 Nov. 1857: 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 18 July 2014.

“Money Market and City Intelligence.” Times [London, England] 17 Nov. 1857: 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 12 August 2014.

“Money-Market and City Intelligence.” Times [London, England] 26 Nov. 1857: 7. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 18 September 2014.

Morgan, Victor E. The Theory and Practice of Central Banking 1797-1913. London: Frank Cass & Co. 1943. Print.

“Select Committee Moved.” Hansard 1803-1905. UK Parliament. House of Commons. Debates. 11 December 1857. Vol. 148 cc 580-672. Web. 15 November 2014. <http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1857/dec/11/select-committee-moved.

“The Suspension of the Bank Act.” The Economist 14 November 1857: 1257-59. Microfilm.

“The Suspension of the Bank Act: Its Real Import and Consequences.” The Economist 21 November 1857: 1286-8. Microfilm.

Tooke, Thomas. An Inquiry into the Currency Principle. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans: 1844. Web. 5 March 2015. http://www.efm.bris.ac.uk/het/tooke/currency.htm

Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Then as Farce. London: Verso, 2009. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Crosby, Mark. “The Bank Restriction Act (1797) and Banknote Forgery”

ENDNOTES

[1] Eric Hobsbawm points out that only the socialists had as yet recognized the “trade cycle” as the “basic rhythm and mode of operation of the capitalist economy” (44).

[2] John Stuart Mill is an exception to this pattern, as is discussed below.

[3] The phrase initially belongs to W. L. Burn, The Age of Equipoise: A Study of the Mid-Victorian Generation who regards the 1850s as an age of consensus. See also Martin Hewitt, ed. An Age of Equipoise?: Reassessing Mid-Victorian Britain for a reassessment of this view.

[4] Hobsbawm points out that “high employment and the readiness to concede temporary wage rises where necessary, blunted the edge of popular discontent” (45).

[5] In 1856, between a quarter and a fifth of all British exports had gone to the United States; in consequence there were many big open credits for American firms in England (J. G. Evans 113). J. H. Clapham states that it was “believed that Britain held £ 80 000 000 of United States stocks and bonds (226).

[6] Both the Currency and Banking schools accept the premise of the gold standard or of convertibility, that is, the idea that bank notes are directly exchangeable with and equal in value to gold. In contrast was the Birmingham school which was against any form of circulation restriction at all, and wished to print money believing “that industry could be helped to expand and consequently unemployment be reduced through the circulation of incontrovertible banknotes” (Edwards 95).

[7] Andréadēs foregrounds the random and fairly paradoxical nature of these edicts, when he says that this sum was arrived at because it was made up the amount of government debt and the amount public securities held by the bank and that a debt is not a very good basis for the issue of notes. The rational conclusion, Andréadēs states, would be that the way to create money would be for the government to borrow it (303).

[8] Silver could not exceed in value more that a quarter of the gold.

[9] No other bank could issue its own banknotes, but if it had been their privilege previously, they were allowed to retain the privilege. J. G. Evans states that banks in England and ![]() Wales were allowed to issue up to fixed limits, calculated on the average issue of the twelve weeks preceding 27th April 1844. Under the Act, seventy-two joint banks and 207 private banks retained the privilege of issuing notes (98).

Wales were allowed to issue up to fixed limits, calculated on the average issue of the twelve weeks preceding 27th April 1844. Under the Act, seventy-two joint banks and 207 private banks retained the privilege of issuing notes (98).

[10] Ledbetter states that during the period that Marx wrote for the paper it enjoyed a readership of more than 200,000 readers, making it the largest newspaper in the world at the time (xviii).

[11] In reference to the circulation war, Horace Greely, the editor of the New York Daily Tribune wrote in 1852: “The Times was crowding us too hard. […] It is conducted with the most policy and the least principle of any paper ever started” (qtd. by Murray Kempton, New York Review of Books 15 June 1967).

[12] Marx alone wrote 350, Engels wrote 125, and together they wrote 12 (Ledbetter xviii).

[13] The piece cited by Marx from The Times was published 26 November 1857. Almost three years before he wrote his articles of late 1857, Marx commented on England’s jingoism and its “self delusion where they believe that they are beyond the unsound system on the Continent and in America” (26 January 1855, Dispatches 166-71).

[14] In the spring and summer of 1857, a committee of the commons was struck to investigate the Bank Act of 1844. The committee was renewed in 1858 to report on the Act and on the recent crisis of late 1857. The Committee found the three main causes of the crisis to be “an unprecedented extension of foreign trade, an excessive importation of precious metals, a monstrous development of banking system as an instrument for the distribution of capital” (D. M. Evans 32).

[15] Gladstone comments on the contradictory nature of the Act that has a “decided and powerful tendency to create an apprehension gradually deepening into panic” and “finally brings about a suspension of the law itself.” Thus, “the very rigour of its provisions in certain states of public feeling and of the public mind becomes an operative cause of the irregular relaxation of the law.” Everybody knows “perfectly well,” he continues, “if they can but stand the gale for a certain time there will come a letter […] signed by the First Lord of the Treasury and the Chancellor of the Exchequer […]. Thus “the force of the Act as a preventive check […] is utterly shattered and destroyed (“Select” 148: 647-8).

[16] Bagehot’s debut in the Economist consisted of a series of twelve letters written through the course of 1857 and early 1858 signed ‘A Banker.’ The question of a larger Bank reserve is raised in his letters to the Editor of 28 November and 5 December 1857, written during the crisis. On 28 November, he argues that since the Bank of England is the lender of last resort, an “unlimited lending establishment” (373), it will be called on “at times of monetary pressure” and “will be almost morally compelled, to give very large amounts of temporary accommodation” (374). He comments again that were we to start “de novo” most men would hesitate to “establish an ultimate treasury for the nation, and would still be more reluctant to bind that treasury by usage and practice to advance indefinitely in times of difficulty.” But given that these practices cannot be altered now, the Bank of England should keep a much larger reserve than it has “lately done” (Collected IX: 377). His 28 November article is followed up with a similar piece published in The Economist on 5 December 1857, 1345-6 where Bagehot again discusses the necessity for an increased reserve for the Bank of England. He states that, since the Bank “has a function as an ultimate lender in times of crisis” and since it had had to provide drastically increased accommodation, the only “moral option […] is to have kept an ampler store of means” (Collected X: 379-80). If the drain had continued longer than it did, the Bank would have been placed in an untenable position.

[17] See Gail Turley Houston for a discussion of the “questionable” nature of the “acceptance of crashes as the price for an ostensibly healthy capitalist economy” manifest in “mainstream theories of crisis” (including those of Mill, Evans, Mills, and Juglar) (18-19). See also S. G. Checkland who states that the fluctuations of the economy “were accepted as the costs of expansion in a market economy” (426).

[18] See Kyun Kim, who states that Mill believed that during depression the “economy moves from one equilibrium to another and production is redirected towards more profitable areas” (21).

[19] Sampson endorses the convening of Parliament in order that it may discover the causes of the Act’s suspension. Lauding the Act once more, he states that this “act placed us virtually in the happy position of a nation with a pure currency subject to no disturbances from the caprices, injustice, or exigencies of Governments, and varying only in accordance with its natural supply [. . .] all mankind will admit we had thus attained a perfect system” (4). Once again, purity and perfection allied with the idea of a “natural supply,” all framed by national pride, are set up against caprice, injustice, and random contingencies.

[20] In disagreement with the Birmingham School, they state that the Bank Act could never have caused the crisis, but that it is “impossible to deny that the legislative and arbitrary limit did aggravate the crisis as that limit was approached and produced the panic that ensued.” The main thrust of the argument, however, is that when Robert Peel relied upon legal regulations affecting the currency to prevent panics and crises “he attached an importance to that element of our monetary system in relation to trade which it did not possess.” Indeed, the argument continues, “there certainly was never a moment in the history of this country, when all the evils he so eloquently described as about to be remedied by the measure which he was proposing, existed in such gigantic magnitude as they do at this moment” (“Crisis,” Economist 28 November1857, 1312-15).